Quite a few schools in our network have cut-back on funding for professional development and have either started limiting the time off or financial support for PD. This is extremely disappointing, as PD can be the lifeblood of educators, and dare I say, particularly for teacher-librarians with their often solitary status within a school. There is however a vast range of ways to get “free” PD in that it will only cost you your own personal time. Here are a few suggestions for things I’ve tried out.

Quite a few schools in our network have cut-back on funding for professional development and have either started limiting the time off or financial support for PD. This is extremely disappointing, as PD can be the lifeblood of educators, and dare I say, particularly for teacher-librarians with their often solitary status within a school. There is however a vast range of ways to get “free” PD in that it will only cost you your own personal time. Here are a few suggestions for things I’ve tried out.

Teach meets

Founded by one of my lecturers in designing spaces for learning, Ewan McIntosh, Just about every major city in the world holds TeachMeets. Basically they’re gatherings for teachers where very brief (5-10 minute) presentations are given on a variety of topics, preceded and followed by some social chitchat and networking. Usually the topics are very practical, actionable “hacks” or ways of solving common teaching questions. In Singapore they’re run by 21stC learning and seem to tend towards the geeky/techie side of things.

Another form of this, for PYP educators is the PYP Connect events. These are run by the Singapore Malaysia PYP network, and consist of longer workshop events hosted by one or another PYP school. Ask your PYP coordinator about the next one in November 2017.

Pros: You get out of your space, meet educators from different specialisations and different schools.

Cons: They’re only a few times a year, and if you can’t attend that’s it.

Read a book (or a blog)

Yup, this can be really really simple. The only tricky bit would be which book to read and finding the time to do so. Basically you need to find your reading tribe. People who share your educational and life philosophy and who are readers and find out what books are shaping their thinking. My criteria for this type of book is one where a chapter can be read and absorbed in the 15-20 minutes between getting into be and my eyes falling shut from exhaustion. At the moment I’m really pleased I found Kylene Beers and Robert Probst’s books

though an ex-colleague. I started by reading Reading Nonfiction and I’m currently on Disrupting Thinking and both books have given plenty of food for thought and initiative for me to reflect on my teaching and literacy practices. They’re just the right balance of practical and thoughtful.

though an ex-colleague. I started by reading Reading Nonfiction and I’m currently on Disrupting Thinking and both books have given plenty of food for thought and initiative for me to reflect on my teaching and literacy practices. They’re just the right balance of practical and thoughtful.

More powerful than just reading a book, is reading with someone or a group of people so that you can share ideas and more importantly, put those ideas into practice. At our school we’ve started running professional book clubs, started by our principal last year when we set up our ODC (Outdoor discover centre) with “Dirty Teaching” . This year we’re running around eight different groups, each with their own focus, based around a book of note. The group I’m in is doing “Making Thinking Visible” and we have (surprise, surprise) a particular focus on using picture books.

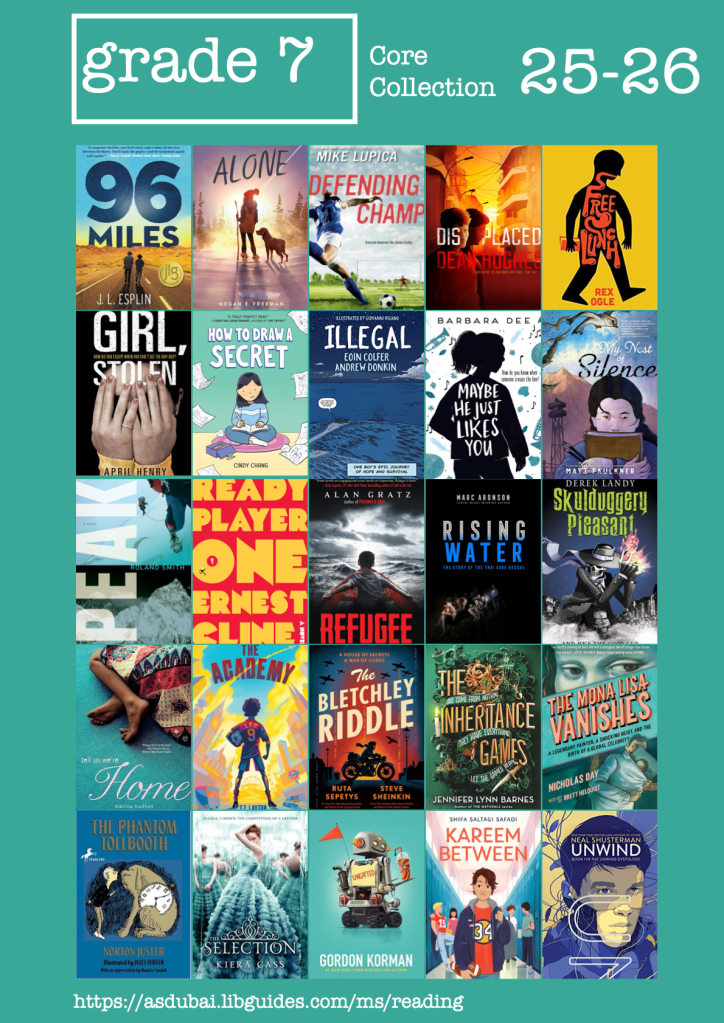

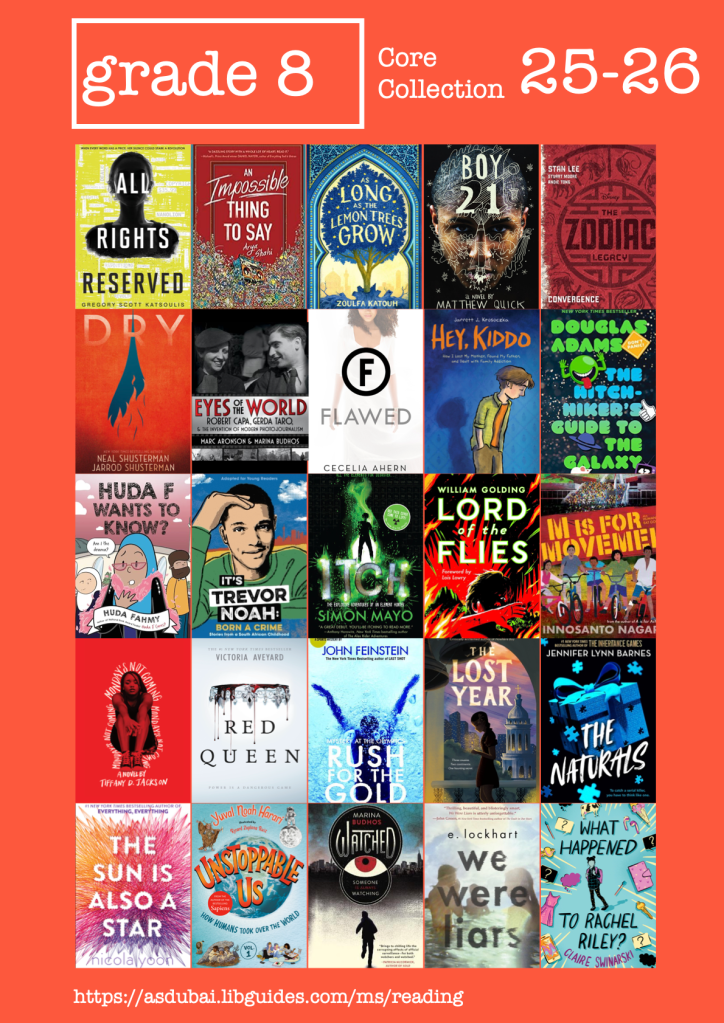

There are plenty of lists of books to read. A word of caution – of course the books on the list reflect the culture of the country / organisation from whence the list is coming. Here are a few: The Guardian (British / Commonwealth focus); Fractus Learning (what I’d call aspirational / holiday read books – not much to put into practice immediately); We are Teachers (USA – more focused on the whole child / success). Funnily / ironically enough there doesn’t seem to be an up to date list for teacher-librarians – the last one was a Goodreads one from 2012, which was pretty meh. Maybe because we’re reading all the time? Maybe it’s time to make one! (Suggestions in comments below).

I know blogging is so 2013, but I still do it, and I still subscribe to a few good blogs such as Hapgood, SLJ blog network, Stephen Downes, Global Literature in Libraries, Gathering Books, and Mrs. ReaderPants. Here is a list of the supposed top 50 librarian blogs (Somewhat USA focused, many not recently updated and nope, I’m not on it)

Pros: You can do it any time / any place. Most books are quickly actionable. A lot of books are now available as audiobooks – so you can multi-task – listen and do exercise etc. (but I need to stop and write notes!)

Cons: You need to dedicate a regular time to reading so that you don’t lose the thread. If you want to join a group, you need to structure it so that you can meet regularly.

Listen to a PodCast

There are so many excellent PodCasts out there – both educational and for general edification. I’m constantly torn between listening to podcasts and to listening to audiobooks. And the best thing is – it really helps your general knowledge, so you and awe your students from time to time!

Some of my favourites for education: The Cult of Pedagogy; Truth for Teachers; 10 minute teacher podcast.

Unfortunately, again teacher librarians are not out there on the podcast scene much, and some of the initial podcasts are not kept up, but to make up for it, there are lots of good book podcasts. My favourite is All the Wonders, because they often feature diverse books and KidLit Radio. The SLJ has The Yarn (which I haven’t listened to but will). Here is another list from The Guardian.

General edification podcasts: 99% Invisible; The Allusionist; The Infinite Monkey Cage; You are Not so Smart; Stuff Mom Never Told You; TED radio hour; RadioLab; Invisibilia; Hidden Brain; Freakonomics; Sources and Methods; and my current favourite In Our Time.

Pros: Anytime, anywhere, keep up with amazing knowledge and information

Cons: So many to choose from. Easy to get behind and iTunes new format for podcasts is AWFUL.

Librarian Groups

Here in Singapore we are most fortune in having the ISLN with regular meetings and access to PD. Besides our quarterly meetings we have regular meet ups on a social basis, and pretty much all our libraries are open for job shadowing and visits. When I was still in training and working part-time, I regularly asked librarians if I could come and spend a day with them, and even now I’m working full time, if my holidays are different to that of my colleagues I’ll often ask if I can come and spend a morning or afternoon with someone, just trailing them with lots of conversations and questions and seeing best practice. Likewise, I encourage my library assistants to spend a day at other libraries from time to time, chatting to the library assistants and picking up some tips and tricks. Likewise, while on holiday, it’s easy to invite yourself to a fellow teacher librarian’s library to have a look around and chat. I’ve recently been to Taipei and popped into TAS’s lovely libraries for a few hours.

Pros: Convenient, local, low barrier

Cons: some librarians do operate in remote areas, or places with vast distances between the libraries making this more difficult.

Webinars

Actually the idea for this post occurred as I signed myself up for a webinar with SLJ. Added to this one could put short courses on YouTube (how I intend to master photoshop, Adobe Illustrator and Adobe InDesign this vacation)

Pros: Most webinars are free, almost all of them have both a live and “after the event” viewing option – ideal if you’re not on American Time.

Cons: The “free” sometimes comes at a cost of at least some of the time being devoted to someone or another trying to sell you their product, but if you already have the product, it can deepen your understanding of how to best use it.

MOOCs

While MOOCs seem to have lost their lustre, they’re still incredibly good for learning stuff. It’s just that the format is so limiting. But be that as it may, you can audit most course free of charge with a small fee to be “qualified”. Over the summer my daughter and I did the exceptionally good 8 week course “Humanity and Nature in Chinese Thought” an introduction to Chinese Philosophy. It has nothing to do with librarianship but everything to do with life and living in a multi-cultural and therefore multi-philosophical environment. I’m currently enrolled in Making Sense of the News: News Literacy Lessons for Digital Citizens; also through HKU, and I’ve done Jo Boaler’s How to Learn Math. No I’m not a math teacher, but I am a math human with math learning students and children.

Pros: Some excellent content; self-paced; you can watch the videos at 1.5/2x speed. Huge variety of offering by some exceptional teachers.

Cons: Video based learning is not my favourite medium. Some courses are only open for a limited time frame. The hype hasn’t quite been realised with the format. Time.

Skype and GoogleHangout

I’ve done this a couple of times in the last few months. During the vacation, I saw an awesome Libguide and I was determined to update my school’s libguides. So I emailed the librarian, and next thing we were having a google hangout and she was screensharing with me showing how she’d done it all!

Then last week I was worrying that I wasn’t using MackinVIA properly, and again reached out to someone who screenshared her set up. I’ve done some libguide training to a fellow librarian who was sitting next to me, while screensharing to another librarian remotely.

Twitter

Great for reaching out to people and keeping up with trends of what is going on. But hard for searching and following threads when you enter part way through is horrid.

Facebook

I put this last because it is truly terrible. The possible worst place in the world to put up information and exchange knowledge. It gets boring and repetitive as the same questions come up time and again. It’s awful for searching, it can be mindless and stupid – why on earth once a question has been asked do people persist on answering it again with the same information?? But the various librarian groups I’m in, are very useful, albeit that I need to keep / store the links immediately to Evernote.

Facebook groups I’ve joined include: Int’l School librarian Connection; SLATT; Global ReadAloud (only really active around the GRA activities in October/November); Future Ready Librarians (tends to be FollettDestiny dominated – the irony Follett and Future!); ISTE librarian Group (not very technological – too much talk about book lists); ALATT (ALA think tank – great for if you are ever mired in self-pity – there are about 30,000 other librarians in way worse a situation than you could ever imagine – ignore the cat photos and memes and sit back and enjoy the political rants on all sides of the US spectrum).

Pros: Amusing, informative, occasional good advice / links; pretty display pictures

Cons: Frustrating format, hard to save; hard to search, huge time suck.

mine. This has the most awful knockoff effect that is unfortunately felt world-wide. Over the summer I toured a number of very prestigious and expensive private (called public there) schools in the UK with my daughter who was looking for 6th form boarding. None of them had the school library on tour, and when we asked to see them, if we were allowed more than a peek through a locked door they were dismal to say the least. Collections were outdated, the library was cramped with limited space and big desktop computers had prominence. But besides that the library had no “presence” at the school in the sense of posters advertising books, announcements, classroom libraries, anything to say that the library was an active and valued part of the community. This is not only a pity for that particular school. Unfortunately the pool of international educators and particularly heads of schools and divisions is often taken from graduates and teachers from these institutions. And of course the

mine. This has the most awful knockoff effect that is unfortunately felt world-wide. Over the summer I toured a number of very prestigious and expensive private (called public there) schools in the UK with my daughter who was looking for 6th form boarding. None of them had the school library on tour, and when we asked to see them, if we were allowed more than a peek through a locked door they were dismal to say the least. Collections were outdated, the library was cramped with limited space and big desktop computers had prominence. But besides that the library had no “presence” at the school in the sense of posters advertising books, announcements, classroom libraries, anything to say that the library was an active and valued part of the community. This is not only a pity for that particular school. Unfortunately the pool of international educators and particularly heads of schools and divisions is often taken from graduates and teachers from these institutions. And of course the

round for dates, documents, links etc. Ordered copies of the books and made sure students didn’t access them prior to the read-aloud, signed up for post-card exchanges and classroom partnerships. Then I subtly and not so subtly pushed teachers into agreeing to try it out. My pitch was basically that it was a great way to kick off literacy right at the start of the year without having to do any preparation besides deciding which parts (if any) of the brilliant Hyperdocs (e.g.

round for dates, documents, links etc. Ordered copies of the books and made sure students didn’t access them prior to the read-aloud, signed up for post-card exchanges and classroom partnerships. Then I subtly and not so subtly pushed teachers into agreeing to try it out. My pitch was basically that it was a great way to kick off literacy right at the start of the year without having to do any preparation besides deciding which parts (if any) of the brilliant Hyperdocs (e.g.

types. When I say I can use, I REALLY can use. I know how to use templates, make an index, do auto-intext citation, add captions, make data tables, pivot tables, look ups, statistical analysis, import addresses into labels etc etc. And what I don’t know I know how to find out how to do, either online or because I know people who know their S*** around this type of stuff. People of my generation and younger. I also have an Education masters in knowledge networks and digital innovation and follow all sorts of trends and tools and try everything at least once. I can use basic HTML and CSS and find out how to do anything if I get stuck. I know how to learn and where to learn anything I need to know and I’m prepared to put in the time to do so. This is in a “just-in- time-and-immediate-application-and-use-basis”, rather than a “just-in-case – and-I’ll-forget it-tomorrow-and-probably-never-use-it-basis”. So can you tell my why I would bother wasting my time and money becoming GAFE (or anything else) diploma’ed when the equivalent is for me to go from driving a high powered sports car to getting a tricycle license? I feel the same way about this as I feel about people saying you don’t need libraries now you have google. Well actually I feel stronger about it. It seems like every single for profit educational technology app or company is now convincing educators that the way for them to be taken seriously is to “certify” themselves on their tools, something that involves a couple of hours of mind-numbingly boring and simple video tutorials and/or multiple choice tests with or without a cheapish fee and then to add a row of downloadable certs into their email signatures like so many degree mill qualifications on a quack’s wall. And then these are held in higher regard (it seems) than the double masters degrees it takes to be a librarian?? Not a game I’m prepared to be playing.

types. When I say I can use, I REALLY can use. I know how to use templates, make an index, do auto-intext citation, add captions, make data tables, pivot tables, look ups, statistical analysis, import addresses into labels etc etc. And what I don’t know I know how to find out how to do, either online or because I know people who know their S*** around this type of stuff. People of my generation and younger. I also have an Education masters in knowledge networks and digital innovation and follow all sorts of trends and tools and try everything at least once. I can use basic HTML and CSS and find out how to do anything if I get stuck. I know how to learn and where to learn anything I need to know and I’m prepared to put in the time to do so. This is in a “just-in- time-and-immediate-application-and-use-basis”, rather than a “just-in-case – and-I’ll-forget it-tomorrow-and-probably-never-use-it-basis”. So can you tell my why I would bother wasting my time and money becoming GAFE (or anything else) diploma’ed when the equivalent is for me to go from driving a high powered sports car to getting a tricycle license? I feel the same way about this as I feel about people saying you don’t need libraries now you have google. Well actually I feel stronger about it. It seems like every single for profit educational technology app or company is now convincing educators that the way for them to be taken seriously is to “certify” themselves on their tools, something that involves a couple of hours of mind-numbingly boring and simple video tutorials and/or multiple choice tests with or without a cheapish fee and then to add a row of downloadable certs into their email signatures like so many degree mill qualifications on a quack’s wall. And then these are held in higher regard (it seems) than the double masters degrees it takes to be a librarian?? Not a game I’m prepared to be playing.

Quite a few schools in our network have cut-back on funding for professional development and have either started limiting the time off or financial support for PD. This is extremely disappointing, as PD can be the lifeblood of educators, and dare I say, particularly for teacher-librarians with their often solitary status within a school. There is however a vast range of ways to get “free” PD in that it will only cost you your own personal time. Here are a few suggestions for things I’ve tried out.

Quite a few schools in our network have cut-back on funding for professional development and have either started limiting the time off or financial support for PD. This is extremely disappointing, as PD can be the lifeblood of educators, and dare I say, particularly for teacher-librarians with their often solitary status within a school. There is however a vast range of ways to get “free” PD in that it will only cost you your own personal time. Here are a few suggestions for things I’ve tried out. though an ex-colleague. I started by reading

though an ex-colleague. I started by reading