I am convinced that there are generations of parents (and librarians) who think the main purpose of a librarian is to create age/grade related lists of books for students to read. When parent-teacher conference time comes around, if parents venture into the library and engage – as opposed to using us as a baby-sitting booth / place to drink coffee and wait / information-direction desk the one and only question they seem to have is “do you have a book list for Grade …”

So why don’t I have a book list for Grade …? When they allow me time to explain, and time to discuss their child(ren)’s reading needs – preferably with the child present these are the themes of the conversation:

What are your (their) favourite things in life?

I don’t start off with what books they like, because their parent(s) probably wouldn’t be having a conversation with me if they liked books or reading. But if I can get a feeling for what kind of person they are, I can start to think what kind of books may be an entry point to intersect with their lives.

I’m very much a “there’s a book for that” type of person and my staff always jokes with me that they can’t have a conversation with me without walking away with a “book for that”. If a student likes gaming, we have gaming books. If they like art and they’re EAL (English as an additional language) I have no problem recommending starting with some of our fabulous wordless books, picture books or graphic novels. And I’m happy to discuss how sharing a (sophisticated or even just funny) picture book together is a way better and more productive use of time than forcing a child to plod through Shakespeare or whatever classic the parent loved when they were young.

Reading, like physical activity and learning, has to leave the person with the desire for more. The feeling that they’d like to keep doing this for a long, long time. Forever in fact. If we make them hate it now, we’re f*’d as a human race.

How much can you read?

This is a little open-ended. It’s a combination of the dreaded “reading level” and how much physical time they have for reading.

We have a lot of EAL students in our school. With very ambitious parents. Who are often well-meaning but misguided. During my 16 years in Asia, I have always been astounded at the high level of education and knowledge my Asian counter-parts have. Newly minted in Asia I had no idea of the classic / foundational texts of their countries / languages / cultures. They knew so much of the western foundational texts – Grimm, Shakespeare, Greek etc. Myths and Legends. I’m always humbled by this. However, they’re not helping their child when they insist that a child with a phase 2 EAL level reads Shakespeare in the original text.

I’ve not got much against Shakespeare (except inasmuch it’s part of the dead white male canon etc. etc.) and I have Shakespeare in my library in every form / format and level. And I’m happy to help these students to start with an abridged version, an illustrated version, a short story version, a graphic novel version. But when what they need is basic foundational functional language so they can survive and thrive in a classroom and canteen, honestly the Plantagenets is not going to help them.

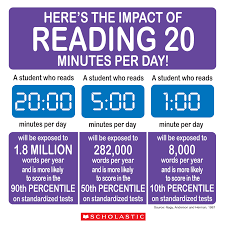

Having time for reading is another big issue. There is this romantic notion that all school-going children read for 20-30 minutes a day. You know all the charts … the funny thing is they all have exactly the same 1987 source, and it’s not even an accurate representation of what the article said – see * below.

I don’t know what your classrooms or homes look like, and I’m sure there are schools, classrooms and homes doing brilliantly on reading. Sustained reading. Uninterrupted reading. I fear the truth is otherwise. I suspect students spend a lot more time on Youtube for their learning. YouTube publishes some interesting statistics. Of relevance is “YouTube is technically the second largest search engine in the world.” and “Average Viewing Session – 40 minutes, up 50% year-over-year”. If I had to put some money on what our students are watching most on YouTube, it wouldn’t be much to do with learning but rather they seem to spend a lot of time watching other students engaged in one kind of game or another.

I think if I had to ask a bunch of our middle-schoolers to preference-rank what they like to do, if reading wasn’t on the list, it wouldn’t even be mentioned. If it was on the list, except for maybe 5-10% of the students it would be way down at the bottom.

So this part is a little about whether the student is able and willing to make time in the day to read, and based on the little perceived time they have, what they could read.

I usually tell students that if they truly are reading every day, they should be able to get through at least a book a week. So the converse is also true. What size, format or type of book can I pair with this student that would guarantee they’d actually finish it in a period of time that will allow the book to remain meaningful?

We have this illusion that if only we could find the “right” book, a student will just want to read it non-stop and then will be converted to reading for life. I don’t think that is true. I think we need to find a succession of books that students will be successful with so that they can build up some kind of reading stamina that will result in them being “good enough” readers so they can be successful academically. And if we’re lucky they’ll pick up a book again after they leave school.

What are your friends reading?

The need to belong is second only to the need to breathe for teenagers. There are glorious moments when we can ride on the wave of “it” books (yes, like Harry Potter). Where there is a buzz around a book or an author that makes it possible for us as librarians to just ensure we have enough copies and that we get out of the way of the stampede to the check-out desk. And make sure we have enough read-alike lists.

That, for teenagers may be the critical bit – the herd immunity thing. Having a critical mass of “cool” students who are readers, who then infect the rest.

My only compromise to lists is having students recommend to each other. Before, when I was in primary and could see each class each week, I had a list per grade. Now, I’ve convinced one grade (6) to make a list as a gift to the incoming class.

What is your teacher reading (aloud) to you?

If only, if only. And when a teacher starts a habit of reading aloud to a class I can guarantee that book will become the favourite of just about every child in that class. Bonus points if the book is the first in a series, because they’ll then rush to complete the series independently.

I’m just going to put out a plug again for the Global ReadAloud. I’ve curated the resources for this year’s books in a Libguide. It’s not too late to start. It’s never too late to start. Just read. Or read and connect. Read now, with the current great list of books. Or read some of the books from previous years. Or read this year’s books now and other books from previous years later. Honestly it doesn’t take much time. I’m reading aloud each morning from Front Desk before school to a small group of students. We have about 10-15 minutes and get through a chapter or two/three depending on the length of the chapter and what else we do / discuss around it.

And this is where I tell parents that if all else fails they should read to-and-with their student. Even if they’re 14. And I tell them how we still read aloud to our IB-level child who also doesn’t like reading. And they look askance at me. Or they make apologies for their own poor reading – and I tell them that’s exactly why they should be reading with their child. As an empathy building exercise. As a gesture of solidarity and understanding that it is not perhaps easy, but it is important. Important enough that we both spend time on this.

Lists are easy to make. Easy to ignore. Conversations are harder, take more time, but potentially have more value. What do you do in your schools / libraries?

————————————————————————————————————————————

*This is where things get very interesting – I went back to the original article and it says nothing like what the posters say … it’s about vocabulary acquisition and learning new words based on context (nothing about standardised tests!). AND they’re talking about students reading 15 minutes IN SCHOOL, plus out-of-school reading of newspapers, magazines and comic books. So the sum for an “average” 5th grader is:

600,000 words in school; 300,000-600,000 words out of school = +/- 1 million words

I doubt the average fifth-grader is reading anything near that amount in or out of school.

” Though the probability of learning a word from context may seem too

small to be of any practical value, one must consider the volume of reading

that children do to properly assess the contribution of learning from context

while reading to long-term vocabulary growth. How much does the average

child read? According to Anderson, Wilson, and Fielding (1986), the

median fifth-grade student reads about 300,000 words per year from books

outside of school; the amount of out-of-school reading increases to about

600,000 words per year if other reading material such as newspapers,

magazines, and comic books are included. If a student read 15 minutes a

day in school (see Allington, 1983; Dishaw, 1977; Leinhardt, Zigmond, &

Cooley, 1981) at 200 words per minute, 200 days per year, 600,000 words

of text would be covered. Thus, a rough estimate of the total annual

volume of reading for a typical fifth-grade student is a million words per

year; many children will easily double this figure. Reanalysis of data

collected by Anderson and Freebody (1983), using information on the

frequency of words in children’s reading material from Carroll, Davies,

and Richman (1971), indicates that a child reading a million words per

year probably encounters roughly 16,000 to 24,000 different unknown

words.

How many words per year do children learn from context while reading,

then? Given a .05 chance of learning a word from context, and an average

amount of reading, a child would learn approximately 800-1,200 words

well enough to pass fairly discriminating multiple-choice items.

These numbers are at the low end of the range that we have previously

estimated (Nagy, Herman, & Anderson, 1985; see also Nagy & Anderson,

1984), because of the lower estimate of the probability of learning a word

from context and a more conservative estimate of the number of unknown

words encountered during reading. Yet, the figures suggest that incidental

learning from written context represents about a third of a child’s annual

vocabulary growth, an increase in absolute vocabulary size that has not

even been approached by any program of direct vocabulary instruction.Nagy, W., Anderson, R.C., & Herman, P. (1987). Learning word meanings from context during normal reading. American Educational Research Journal, 24, 237–270

This time the exercise really did work – on reflection, the “warm up” possibly did help the success, despite not being optimal, because the students just weren’t used to giving their own views and in the first half kept looking to the adults for the “right / expected answer”. We had some powerful contributions from the groups, and some very interesting movement from utter condemnation for the father’s behaviour to understanding and empathy for the context and actions. And also the feeling that they could use this in their personal and academic lives.

This time the exercise really did work – on reflection, the “warm up” possibly did help the success, despite not being optimal, because the students just weren’t used to giving their own views and in the first half kept looking to the adults for the “right / expected answer”. We had some powerful contributions from the groups, and some very interesting movement from utter condemnation for the father’s behaviour to understanding and empathy for the context and actions. And also the feeling that they could use this in their personal and academic lives.