Classical retellings

Green Gables Fables (Anne of Green Gables)

|

| https://www.youtube.com/user/greengablesfables

|

Lizzie Bennet Diaries (Pride and Prejudice)

|

| http://www.pemberleydigital.com/the-lizzie-bennet-diaries/ |

Frankenstein – Inkle Studios

|

http://www.inklestudios.com/frankenstein/

Frankenstein MD – Vlog |

|

| http://www.pemberleydigital.com/frankenstein-md/ |

Greek Myths – Twitterature

|

| https://storify.com/CrownPublishing/100-greek-myths-retold-in-100-tweets |

Greek Myths – retold by vegetables

|

| http://www.openculture.com/2014/08/the-story-of-oedipus-retold-with-vegetables-in-starring-roles.html |

Digital literature – Interactive documentaries

Here are a few interactive documentaries I think are particularly good.

The Guardian – First World War

|

| http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2014/jul/23/a-global-guide-to-the-first-world-war-interactive-documentary |

New York Times – Story of the high rise

|

| http://www.nytimes.com/projects/2013/high-rise/ A short history of the high rise |

Welcome to Pine Point NFB Canada

|

| http://pinepoint.nfb.ca/#/pinepoint |

Firestorm – The Guardian

What is twitterature?

https://embed-ssl.ted.com/talks/andrew_fitzgerald_adventures_in_twitter_fiction.html

Viking / Penguin have taken the lead in this new format and there is a dedicated website to some of the best examples.

The myth of "reluctance"?

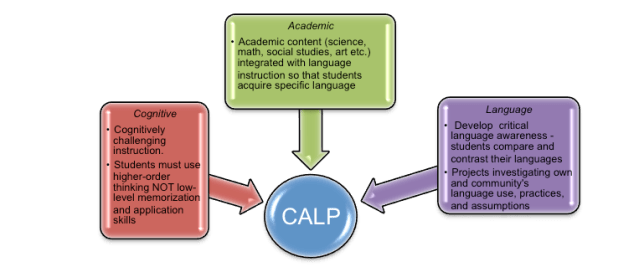

Dr Jim Cummins explains the differences between BICS and CALP. from Teach Away Inc. on Vimeo.

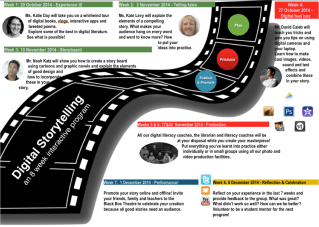

Digital Storytelling – an 8-week interactive program for Middle School students

____________________________________________________________________

Assessment Item 1: Report and program for specified age group

INF 505 – Library Services for Children and Youth

___________________________________________________________________

Part 1: Background and context

|

Section

|

Number

|

|

Kindergarten

|

353

|

|

Primary School

|

654

|

|

Middle School

|

587

|

|

High School

|

324

|

|

IB

|

321

|

|

Total

|

2,239

|

Part 2: Design and develop a program

Goals and objectives

|

Objective

|

Relevance

|

Related Developmental need

|

|

1. Introduce students to concepts, examples and tools of digital storytelling

|

Students are familiar with literature and with digital tools, however not with digital storytelling. This will broaden their competencies while scaffolding on what they already know.

|

Competence and achievement

Structure and clear limits |

|

2. Support students in the creation of their own narratives using the tools of digital storytelling

|

For successful creative output, students will need technical, literacy and social support in an encouraging non-judgmental environment

|

Creative expression

Positive social interaction with Adults and Peers Competence and Achievement Opportunities for Self-definition |

|

3. Provide a forum for sharing, promotion, collaboration and interaction

|

Student’s digital storytelling outputs receive validation through providing an appreciative audience while allowing them to contribute the same to their fellow participants.

|

Positive social interaction with Adults and peers

Meaningful participation |

Figure 2: Objectives, relevance and developmental needs

Cost, staffing and other logistical considerations

Program delivery

Week 1: Experience it!

Week 2: Telling Tales

Week 3: Storyboard

Week 4: Digital tool box

Weeks 5 & 6: Production

Week 7: Performance

Week 8: Reflection and celebration

Detailed activity plan – Week 1

Materials required

|

Type

|

Name

|

Link

|

|

Interactive Documentary

|

A global guide to the first world war (Panetta, 2014)

|

|

|

Twitterature

|

100 Greek Myths retold in 100 tweets (Crown Publishing, 2012)

|

|

|

Digital Novel

|

Inanimate Alice (DreamingMethods, 2012)

|

|

|

Vlog

|

Lizzie Bennet Diaries (Su, Noble, Rorick, & Austen, 2014)

|

|

|

Animated dreamtime stories

|

Dust Echoes (ABC, 2007)

|

|

|

iPad app and eBook

|

Shakespeare in Bits – Romeo and Juliette (Mindconnex Learning Ltd, 2012)

|

Figure 4: Digital Literature examples for screening

Step by step procedures of what is to be done

|

Item

|

Equipment / Material

|

Timing

|

|

Greet students and ask for a brief introduction with name, class, where they are from and any experience or expectations they have from the program.

|

Stickers for students to write the names on

|

10 minutes

|

|

Perform a short icebreaker such as “two truths and one lie” with students in pairs.

|

n/a

|

10 minutes

|

|

Ask students to do initial survey using google forms.

|

Survey (Appendix 3)

|

5 minutes

|

|

Show snippets of the first three examples of digital story telling – A Global guide to the first world war, 100 Greek Myths and Inanimate Alice.

|

Laptop, projector and screen. Ensure various resources are open to minimise turnover time

|

3 resources, 5 minutes each = 15 minutes

|

|

Open discussion on what appeals to the students

|

Use the elements of successful digital story telling i.e. Interactive; Authentic; Meaningful; Technological; Organized; Productive; Collaborative; Appealing; Motivating; and Personalized (Yoon, 2013) to scaffold activity

|

20 minutes

|

|

Give students a break to have a snack, use the washroom, etc.

|

10 minutes

|

|

|

Show snippets of the next three examples of digital story telling – Lizzie Bennet Diaries, Dust Echoes and Shakespeare in Bits – Romeo and Juliette.

|

Laptop, projector and screen. Ensure various resources are open to minimise turnover time.

|

3 resources, 5 minutes each = 15 minutes

|

|

Ask students to choose the type of digital storytelling that most appeals to them; they can explore the resource in the remaining class time and borrow the resource to explore further at home.

|

Assist with loan and downloading of materials or searching of similar materials.

|

20 minutes

|

|

Finish in time for buses / pickup

|

Total 1 hour 45 minutes

|

Figure 5: Step by Step Procedure for week 1

Audience, staffing and other considerations

Marketing and promotion

Part 3: Evaluation and reflection

How to evaluate the program

Reflection

|

Objective

|

|

1. Introduce students to concepts, examples and tools of digital storytelling

|

|

2. Support students in the creation of their own narratives using the tools of digital storytelling

|

|

3. Provide a forum for sharing, promotion, collaboration and interaction

|

Figure 7: Objectives revisited

|

Developmental Need

|

Expression

|

Program Objectives

|

Program characteristics

|

|

Positive Social Interaction with Adults & Peers

|

Seek attention, socialization

|

2, 3

|

Small group of students with specialist teachers with a variety of skills and personalities

|

|

Structure & Clear Limits

|

Push boundaries, challenge authority

|

1, 2, 3

|

Program is limited to 8 sessions with a clear structure within which choice and autonomy is possible

|

|

Physical Activity

|

Running, jostling, roaming

|

n/a

|

Not applicable

|

|

Creative Expression

|

Vandalism, Vine, Instagram, Snapchat

|

2

|

Creative storytelling is the main thrust of the program

|

|

Competence & Achievement

|

Competitive behaviour, Minecraft, number of followers on social media

|

1,2,3

|

The program allows for mastery of technological and storytelling skills within a new format, end result is performed and published

|

|

Meaningful Participation

|

Opinionated, socialization, clique club or team membership

|

2, 3

|

Activities allow for interaction in the physical and virtual space

|

|

Opportunities for Self-Definition

|

Status symbols, dress and hair,

|

2

|

Students are encouraged to consider their culture, linguistic and social identities in producing their story

|

Figure 8: Summary of developmental needs, expression, program objectives and characteristics

References

ABC. (2007). Dust Echoes. Retrieved August 20, 2014, from http://www.abc.net.au/dustechoes/dustEchoesFlash.htm

Barnard, C., A. (2011). How Can Teachers Implement Multiple Modalities into the Classroom to Assist Struggling Male Readers? (Education Masters Paper 26). St. John Fisher College, Rochester, NY.

Beach, R. (2012). Uses of Digital Tools and Literacies in the English Language Arts Classroom. Research in the Schools, 19(1), 45–59.

Buchholz, B. (2014). “Actually, that’s not really how I imagined it”: Children’s divergent dispositions, identities, and practices in digital production. In Working Papers in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education (Vol. 3, pp. 25–53). Bloomington, IN: School of Education, Indiana University. Retrieved from http://education.indiana.edu/graduate/programs/literacy-culture-language/specialty/wplcle/index.html

Burke, Q., & Kafai, Y. B. (2012). The writers’ workshop for youth programmers: digital storytelling with scratch in middle school classrooms (pp. 433–438). Presented at the Proceedings of the 43rd ACM technical symposium on Computer Science Education, ACM.

Crown Publishing. (2012, November). @LucyCoats: 100 Greek Myths Retold in 100 Tweets (with tweets). Retrieved September 4, 2014, from https://storify.com/CrownPublishing/100-greek-myths-retold-in-100-tweets

DreamingMethods. (2012). Inanimate Alice – About the Project [Digital Novel]. Retrieved September 4, 2014, from http://www.inanimatealice.com/about.html

Dreon, O., Kerper, R. M., & Landis, J. (2011). Digital Storytelling: A Tool for Teaching and Learning in the YouTube Generation. Middle School Journal, 42(5), 4–9.

Gallaway, B. (2008). Pain in the Brain: Teen Library (mis)Behavior. Retrieved September 4, 2014, from http://www.slideshare.net/informationgoddess29/pain-in-the-brain-teen-library-misbehavior-presentation

Gorrindo, T., Fishel, A., & Beresin, E. (2012). Understanding Technology Use Throughout Development: What Erik Erikson Would Say About Toddler Tweets and Facebook Friends. Focus, X(3), 282–292. Retrieved from http://focus.psychiatryonline.org/data/Journals/FOCUS/24947/282.pdf

Green, M. R. (2011). Writing in the Digital Environment: Pre-service Teachers’ Perceptions of the Value of Digital Storytelling. In American Educational Research Association (pp. 8–12). Retrieved from http://worldroom.tamu.edu/Workshops/Storytelling13/Articles/Green.pdf

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., & Hughes, J. E. (2009). Learning, Teaching, and Scholarship in a Digital Age: Web 2.0 and Classroom Research: What Path Should We Take Now? Educational Researcher, 38(4), 246–259. doi:10.3102/0013189X09336671

Gunter, G. A., & Kenny, R. F. (2008). Digital booktalk: Digital media for reluctant readers. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 8(1), 84–99.

Gunter, G. A., & Kenny, R. F. (2012). UB the director: Utilizing digital book trailers to engage gifted and twice-exceptional students in reading. Gifted Education International, 28(2), 146–160. doi:10.1177/0261429412440378

Hall, M., Hall, L., Hodgson, J., Hume, C., & Humphries, L. (2012). Scaffolding the Story Creation Process. In 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education. Porto, Portugal. Retrieved from http://www.lynnehall.co.uk/pubs/ScaffoldingTheStoryCreationProcess.pdf

Jones, P., & Waddle, L. L. (2002). New directions for library service to young adults. Chicago: American Library Association.

Kenny, R. F. (2011). Beyond the Gutenberg Parenthesis: Exploring New Paradigms in Media and Learning. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 3(1), 32–46. Retrieved from http://www.jmle.org

Kenny, R. F., & Gunter, G. A. (2004). Digital booktalk: Pairing books with potential readers. Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 27, 330–338.

Knight, S. (2012, June 20). Introduction to Digital Storytelling. Retrieved September 6, 2014, from http://www.slideshare.net/sknight/digital-storytelling-ed554?related=1

Meyers, E. M., Fisher, K. E., & Marcoux, E. (2007). Studying the everyday information behavior of tweens: Notes from the field. Library & Information Science Research, 29(3), 310–331. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2007.04.011

Mindconnex Learning Ltd. (2012, January 25). Shakespeare In Bits: Romeo & Juliet iPad Edition on the App Store [iTunes]. Retrieved September 6, 2014, from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/shakespeare-in-bits-romeo/id370803660?mt=8

Morgan, H. (2014). Using digital story projects to help students improve in reading and writing. Reading Improvement, 51(1), 20–26. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1540737338?accountid=10344

Musil, R. (2001). The confusions of young Törless. (S. Whiteside, Trans.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books.

Nilsson, M. (2010). Developing Voice in Digital Storytelling Through Creativity, Narrative and Multimodality. International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 6(2), 148–160. Retrieved from http://seminar.net/index.php/volume-6-issue-2-2010/154-developing-voice-in-digital-storytelling-through-creativity-narrative-and-multimodality

Panetta, F. (2014). A global guide to the First World War [Interactive documentary]. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2014/jul/23/a-global-guide-to-the-first-world-war-interactive-documentary

Ragen, M. (2012). Inspired technology, inspired readers: How book trailers foster a passion for reading. Access, 26(1), 8–13. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/934354989?accountid=10344

Reynolds, G. (2008). Chapter 6 Presentation Design: Principles and Techniques. In Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery (pp. 152–163). New Riders. Retrieved from http://www.presentationzen.com/chapter6_spread.pdf

Su, B., Noble, K., Rorick, K., & Austen, J. (2014). The secret diary of Lizzie Bennet. London ; Sydney: Simon & Schuster.

Thompson, I. (2012). Stimulating reluctant writers: a Vygotskian approach to teaching writing in secondary schools: Stimulating reluctant writers. English in Education, 46(1), 85–100. doi:10.1111/j.1754-8845.2011.01117.x

UWCSEA. (n.d.). Languages at UWCSEA. Retrieved from http://issuu.com/uwcsea/docs/uwcsea_languages

Yoon, T. (2013). Are you digitized? Ways to provide motivation for ELLs using digital storytelling. International Journal of Research Studies in Educational Technology, 2(1). doi:10.5861/ijrset.2012.204

Appendix 1: Program Overview

|

Element

|

Synopsis

|

Relevance

|

Instructor

|

Location

|

|

|

Week 1:

20 October 2014

|

Experience it!

|

A whirlwind tour of digital books, vlogs, interactive apps and tweeted poems.

|

Provide background to program and give understanding of what is possible.

|

Ms. Katie Day – secondary school librarian – expert in YA literature

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 2:

27 October 2014

|

Telling tales

|

Elements of storytelling explained with particular reference to digital storytelling.

|

Storytelling, no matter what the medium is the basis of this program.

|

Ms. Kate Levy – high school English teacher

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 3:

3 November 2014

|

Storyboard

|

Students shown how to create a storyboard using the example of cartoons and graphic novels and elements of good design are introduced.

|

Learn the elements of good design and how to incorporate these in your story.

|

Mr. Noah Katz – visual literacy coach

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 4:

10 November 2014

|

Digital tool box

|

Digital tools for capturing and combining different modal choices (image, sound, text) are explained. Best practise is highlighted.

|

Bring students digital skills to a comparative level of mastery and show how to incorporate into their storytelling.

|

Mr. David Caleb – digital literacy coach, photographer and author of “The Photographer’s Toolkit”

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 5:

17 November 2014

|

Production

|

Students will be given the time and resources to put their ideas and skills into practise. They can choose between individual, paired or group production.

|

Students will be aided in their creation of digital stories by competent experts they can achieve their creative goals within a clear structure.

|

All 7 school digital literacy coaches, librarian and Ms. Levy

|

Library – Emily Dickinson, Pablo Neruda rooms & Think Tank – green, blue or white screens available

|

|

Week 6:

24 November 2014

|

Production

|

||||

|

Week 7:

1 December 2014

|

Performance!

|

Output is produced and promoted. Friends, family and teachers are invited to the Black Box Theatre watch the digital storytelling productions.

|

An explicit audience is an important aspect of storytelling. Students will have a sense of competency and achievement.

|

Ms. Katie Day, participants, digital literacy coaches

|

Black Box Theatre

|

|

Week 8:

8 December 2014

|

Reflection

|

Time is given for reflection and feedback of the last 7 weeks. The end results are celebrated and promoted further.

|

The end of the program is indicated by this activity both setting a limit to the formal program and allowing reflection and also validating participants by requesting their evaluation and suggestions for improvement.

|

All instructors

|

Library Think Tank

|

Appendix 2: Promotional Calendar

Appendix 3: Pre-program Survey

|

Definitely

|

Usually

|

Some-what

|

Not really

|

Not at all

|

|

|

I enjoy reading or watching

|

|||||

|

Fiction, stories, memoirs

|

|||||

|

Non-fiction or documentaries

|

|||||

|

Poetry

|

|||||

|

I can use the following technology

|

|||||

|

Digital Camera

|

|||||

|

Digital Video Camera

|

|||||

|

iPhoto

|

|||||

|

Photoshop

|

|||||

|

iTunes

|

|||||

|

Garage Band

|

|||||

|

iMovie

|

|||||

|

I use the following social media

|

|||||

|

Facebook

|

|||||

|

Instagram

|

|||||

|

Twitter

|

|||||

|

YouTube

|

|||||

|

Other – please state which ……

|

|||||

|

I express my creativity through

|

|||||

|

Writing

|

|||||

|

Art or photography

|

|||||

|

Music or dance

|

|||||

|

Drama and acting

|

|||||

|

Video or film

|

|||||

|

I am not creative

|

|||||

|

What do you expect from this program?

|

|||||

Appendix 4: Post Program Survey

|

Definitely

|

Usually

|

Some-what

|

Not really

|

Not at all

|

|

|

I understand the concepts and tools of Digital Storytelling

|

|||||

|

Different types of digital stories

|

|||||

|

What is important in storytelling

|

|||||

|

How to create a storyboard

|

|||||

|

I can produce my own digital story

|

|||||

|

I can use the following technology

|

|||||

|

Digital Camera

|

|||||

|

Digital Video Camera

|

|||||

|

iPhoto

|

|||||

|

Photoshop

|

|||||

|

iTunes

|

|||||

|

Garage Band

|

|||||

|

iMovie

|

|||||

|

I would recommend this program

|

|||||

|

To friends / classmates

|

|||||

|

To teachers

|

|||||

|

What was the best / most positive part of this program?

|

|||||

|

What didn’t you enjoy about this program?

|

|||||

|

What improvements would you suggest?

|

|||||

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Building a LOTE collection at an International School

Most international schools have a sizeable student population who speak a language other than English (LOTE), and offer language instruction in either mother tongue or second language at various levels. The question then is what role the school library plays in building a LOTE collection and how this can be financed and what other options exist.

Both the IBO (International Baccalaureate Organisation) and UNESCO encourage schools and learning communities to provide active support to promote learning and maintenance of mother tongue (Morley, 2006; UNESCO Bangkok, 2007). A school library’s aim should be to ensure that the LOTE collection supports the aims of the school for classroom instruction and external examination, pleasure reading and exposure to the literature of the various cultures of the campus community.

A review of the LOTE collection can be undertaken in the following steps: an overview of the existing collection; information gathering on the language profiles of the school community (students, parents, educators); understanding of the language provision at the school including mother tongue and second language acquisition; reviewing LOTE collections in the community; creating a LOTE collection development policy and other considerations.

Overview of the existing collection

Initially it is important to gain an overview of the school’s existing collection and how that is catalogued. If our school is anything to go by, there will be reading books, language text books (temporarily as they get loaned out at the start of the school year), and language teaching resources for teachers in the library. Those are the books we know of. However, depending on how tightly or loosely the library manages resources, individual language departments or teachers may have anything from vast to tiny collections in their classrooms purchased by departmental budgets (or often the purse of the teacher) which are neither catalogued by the library nor even known of outside of that department. This will differ from school to school depending on the amount of control the library has over resource budgets, the amount of sharing that goes on and the co-operation between the library and departments.

Even finding out the extent and location of resources can potentially be a political minefield, so proceed with caution and bear in mind what may seem to be an innocent question / request on your side may be misinterpreted on theirs …

Language profile of the school community

Try to understand the language profile of your school community. Are there any significant language groups within the student, parent or educator body? Think carefully where you get this information from – for example if the school is English medium, parents may put “English” as the mother tongue and the mother tongue as a second language or even omit other languages spoken at home completely in any admissions documents. Hopefully the school does some kind of census that is separate from the admissions process. Does the Parent Association have language or nationality representatives who can support the library, financially or otherwise?

Understanding school’s language provision

In addition you need to establish how many students follow which language streams in the various sections of the school, and gain an understanding of the various levels. Hopefully language teachers are cooperative and enthusiastic in explaining the needs of their students for books that encourage reading outside and around the curriculum and for pleasure, not just what is required in the classroom. They should also be able to help with the levelling of materials to ensure a culture of reading is sustained in all languages not just English and students are not frustrated with the complexity of materials available but the library has a range of materials at all difficultly levels.

Reviewing LOTE collections in the community

In the International / expatriate community, LOTE collections often exist outside of the school. Need for LOTE resources in a particular language is not necessarily a function of number of L1 (mother tongue) or L2 (second language) speakers. For example in Singapore, a few sizeable language communities (Korean, Japanese, and to a certain extent Dutch and French) rely on language and culture centres in Singapore spo

nsored in part by their National Governments, while the Singapore National Library holds Chinese, Malay and Tamil books. The role of the library would be one of collaboration and directing these populations to the relevant resource, (e.g. through the website and inter-library loans) rather than building up a potentially redundant collection. If the community has any International schools that focus primarily on one language (in Singapore this includes the German, French, Dutch, Korean and Japanese schools each with their own library), they could be approached for reciprocal borrowing or interlibrary loan privileges. Embassy and cultural attaches may be another source of funding or resources.

Creating a LOTE collection development policy

Depending on the size and status of the LOTE collection, it may not be necessary to create a separate LOTE collection development policy (CDP). LOTE collection issues can be dealt with within the overall CDP.

For example, the library strives to a goal of up to 20 books, excluding textbooks, per student. LOTE books can be expressed as a meaningful percentage per language of this aim.

Provision should be made for language teachers selecting books with input from parents or native speakers in the college community. Use can made of various recommendation lists including that of the IB Organisation (IBO) and collaborative lists of the International School Library Networks and language specialist schools.

Acquisition may be a tricky areas where books are either not available locally, are prohibitively expensive or are not shipped to the country. Provision often needs to be made for the acquisition by teachers, parents or students during home leave and reimbursed by the school. However, the budget and type of books needs to be vetted in advance so that there is little chance of miscommunication on either the cost or type of books thus acquired. A LOTE selection profile, such as that created by Caval Languages Direct (Caval. n.d.) can be adapted to fit the school’s needs.

As far as possible, it would be helpful if the library processes and catalogues all books which the school has paid for, irrespective of whether it came from the library budget or not. In this way, the real collection is transparent, searchable and available to the whole community (on request obviously for classroom / department materials) and to avoid duplication in acquisition or under-utilisation of materials.

Cataloguing LOTE materials can be a challenge, particularly if they are not in Latin script. It is important to still have cataloguing guidelines that are followed to ensure consistency and ease of search and retrieval. Our school makes use of parent volunteers and teachers who fill the data into a spreadsheet that is then imported into our OPAC system. Our convention is to have the title details in script, followed by transliteration, followed by translation in English. Search terms need to be agreed with by the LOTE collection users, such as language teachers and students.

As far as donations are concerned, the library still needs to have a clear policy on what books they accept and in what condition. Although donated books may be “free”, they are not without cost, including processing and cataloguing cost.

Apart from physical books, it is worthwhile looking at what resources are available online either as eBooks or as other digital resources. For example BookFlix and TumbleBooks offer materials in Spanish. Often individual language departments maintain their own lists and links to digital resources, which could be incorporated into a Library Guide and made available to the whole community.

Budget may be a contentious area and often language material discussions occur at administration or department level without the involvement of the library and an expectation may exist that the library will provide LOTE “leisure reading” materials within its overall resource budget perhaps without an explicit discussion on the matter or a breakdown between resources and budget of the various languages.

Other considerations

International schools are a dynamic environment, and a language group may be dominant for a period of time and then disappear completely due to the investment or disinvestment of multi-national companies in the area. IB schools face the need to provide for self-taught languages and any changes made by the IBO and the school from time to time. The IBO currently offers 55 languages, which theoretically could be chosen. The IBO introduced changes in its language curriculum in 2011, substantially increasing the number of works that need to be studied in the original language rather than in translation. This places an additional burden on the library to have sufficient texts in the correct language available on time.

The socio-economic demographic of students with LOTE needs should also be considered. If most of the student body comes from a privileged background where LOTE books are purchased during home leave, the school could institute donation drives where “outgrown” books are donated to the school. It would be more equitable to use resources for scholarship students in order to maintain their L1 even if these languages do not form a large part of the communities’ LOTE.

The quality of materials in Southeast Asian languages is generally extremely poor. The cost of acquiring, processing and cataloguing the materials far exceeds the purchase price and books deteriorate rapidly. There is considerable scope for moving to digital materials, however the availability, format, access, licensing issues and compatibility will have to be investigated.

Schools, in conjunction with parents, needs to consider language provision for students who plan on returning to a LOTE university after graduation.

Centres of Excellence

A literature review suggests that the centre for excellence and expertise in building LOTE collections is Victoria Australia, (Library and Archives Canada, 2009), in fact the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Multicultural Communities Guidelines for Library services is based on their guidelines (IFLA, 1996). These guidelines suggest the four steps of; needs identification and continual assessment, service planning for the range of resource and service need, plan implementation and service evaluation.

Some LOTE Digital resources

http://librivox.org/about-listening-to-librivox/

http://www.radiobooks.eu/index.php?lang=EN

http://www.booksshouldbefree.com/language/Dutch

http://www.childrenslibrary.org/icdl/SimpleSearchCategory

Library services

http://www.lote-librariesdirect.com.au/contact/

http://www.caval.edu.au/solutions/language-resources

http://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/lotelibrary/index.html

http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/services/multicultural/multicultural_services_public_libraries.html

http://www.reforma.org/content.asp?pl=9&sl=59&contentid=59

http://chopac.org/cgi-bin/tools/azorder.pl

http://civicalld.com/our-services/collection-services

References

American Library Association. (2007). How to Serve the World @ your library. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.ala.org/offices/olos/toolkits/servetheworld/servetheworldhome

International Baccalaureate Organisation. (2011). Guide for governments and universities on the changes in the Diploma Programme groups 1 and 2. IBO. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/recognition/dpchanges/documents/Guide_e.pdf

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (1996). Multicultural Communities Guideline for Library Services. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://archive.ifla.org/VII/s32/pub/guide-e.htm

Kennedy, J., & Charles Sturt University. Centre for Information Studies. (2006). Collection management : a concise introduction. Wagga Wagga, N.S.W.: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

Library and Archives Canada. (2009). Multicultural Resources and Services – Toolkit – Developing Multicultural Collections. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/multicultural/005007-302-e.html

Morley, K. (2006). Mother Tongue Maintenance – Schools Assisted Self-Taught A1 Languages. Presented at the Global Convention on Language Issues and Bilingual Education, Singapore. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/news/documents/morley2.pdf

Reference & User Services Association. (1997). Guidelines for the Development and Promotion of Multilingual Collections and Services. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines/guidemultilingual

UNESCO Bangkok. (2008). Improving the Quality of Mother Tongue-based Literacy and Learning Case Studies from Asia, Africa and South America. UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education Asia-Pacific Programme of Education for All (APPEAL). Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001777/177738e.pdf

Creative Commons License

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Language, Bilingualism and Multi-lingualism in the news

There is a lot of information out there (I’ve found 575 articles in the last year alone), and there is a lot of repetition and there is a lot of nonsense, but plenty of gems as well. Published “as it comes” and up to the reader to educate themselves and separate the hype from the reality.

Get flipboard here: https://about.flipboard.com/

And follow this board here: https://flipboard.com/section/bilingualism%2C-mother-tongue-%26-language-bxo7KX

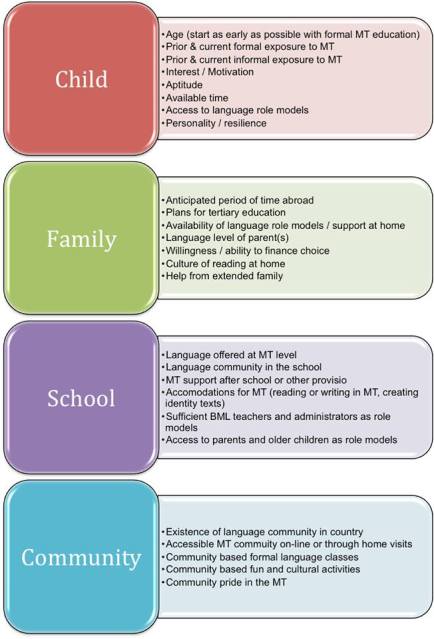

Mother Tongue – How to assess your likelihood of success

First I present the table of factors, and then I present myself filling in this table as an exercise in my own home.

Analysis: The theories of MT acquisition and maintenance versus the reality of our situation

|

Theory

|

Reality – Chinese

|

Reality – Dutch

|

|

|

Child

|

Age (start as early as possible with formal MT education)

|

Both started Chinese immersion in Grade 1 (age 6)

|

Son started formal Dutch in Grade 5 (age 10)

|

|

Prior & current formal exposure to MT

|

1 hour per day class in International School

|

None

|

|

|

Prior & current informal exposure to MT

|

Not much – Hong Kong is Cantonese not Mandarin speaking. Daughter did learn characters through observation on the street.

|

Dutch spoken at home, exposure through paternal grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins.

|

|

|

Interest / Motivation

|

Daughter – High;

Son – Low |

Daughter not particularly interested, speaks on holiday and to family

Son – High

|

|

|

Aptitude

|

Daughter – excellent memory which is necessary for amount of memorization necessary

Son – difficulties with working memory due to ADHD doesn’t rely on memory for learning

|

Son – very good ear and pronunciation, has taken well to spelling and grammar as it’s taught in a formal structured way (unlike English)

|

|

|

Available time

|

In HK had ample time (27/28 hours a week in class plus a lot of homework)

Daughter: in SG 5x 40 minutes a week class time, 90 minutes a week tutoring, 100 minutes a week required homework plus whatever time she has for self-motivated study and reading

|

5 x 40 minutes a week class time (1x of which is self-study)

1 x 120 minutes after school tutoring.

Homework around 60 minutes

Daily reading expected 15-20 minutes (doesn’t always happen)

|

|

|

Access to language role models

|

Limited to school and tutor and one family friend who we see irregularly

|

Parents speak Dutch at home to each other, Father speaks Dutch to him, Mother speaks English unless in Dutch context

|

|

|

Personality / resilience

|

Very determined, sees events as challenges rather than setbacks, competitive, responds well to reward systems, perfectionist, introverted and shy

|

Very sociable, extroverted, not scared of making mistakes. Quite emotional, inclined to give up when things get difficult, or need help to keep going

|

|

|

Family

|

Anticipated period of time abroad

|

Indefinite

|

Indefinite

|

|

Plans for tertiary education

|

Undecided, probably English medium

|

Considering studying film or photography in Netherlands (early thoughts)

|

|

|

Availability of language role models / support at home

|

Mother studied Chinese but level is not sufficient to support high level language and literacy needs practically, only in abstract

|

Both Mother and father speak Dutch in the home

|

|

|

Language level of parent(s)

|

Mother – Low level

Father – none

|

Mother – Fluent speaking reading, listening, written poor

Father – Fluent speaking, reading, listening, writing

|

|

|

Willingness / ability to finance choice

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

|

Culture of reading at home

|

Yes – but needs prompting and encouragement as slow difficult process and access to the right leveled material is difficult.

|

Yes – when father is home do co-reading as well

|

|

|

Help from extended family

|

None, only moral support

|

Yes – regular phone calls / FaceTime, visits during vacation and go to school with cousins for a few days

|

|

|

School

|

Language offered at MT level

|

Yes in theory. However in practice the amount of time and level is not adequate, plus not enough leveled reading resources and mentoring

|

None in curriculum until G9. In G7 & G8 offered after school. His Dutch classes are an exception and privately arranged and funded

|

|

Language community in the school

|

Yes, however she is not particularly a part of it.

|

Yes

|

|

|

MT support after school or other proviso

|

Yes, 90 minutes private tutoring after school, school provides walk in clinics 2x a week

|

Only from G7, however he’s not at the level required yet

|

|

|

Accommodations for MT (reading or writing in MT, creating identity texts)

|

Yes, in school (since middle school only) and tutor supplements

|

Yes, but still limited due to level

|

|

|

Sufficient BML teachers and administrators as role models

|

Administration & non-language teachers traditionally English / mono-lingual with some exceptions. This is changing a bit.

|

Administration & non-language teachers traditionally English / mono-lingual with some exceptions. This is changing a bit.

|

|

|

Access to parents and older children as role models

|

In principal – but need to tap into this more. No formal structures.

|

Yes, cultural events organized by Dutch Teacher.

|

|

|

Community

|

Existence of language community in country

|

Yes, large Chinese speaking population, however local families are not part of school

|

Yes, Dutch club and fair sized community with events

|

|

Accessible MT community on-line or through home visits

|

Possibly – not investigated yet

|

Yes

|

|

|

Community based formal language classes

|

Many tutoring schools that cater to the Chinese curriculum of local schools

|

Yes

|

|

|

Community based fun and cultural activities

|

Not as many as in Hong Kong

|

Yes through Dutch club and school

|

|

|

Community pride in the MT

|

Many classmates in MT group are not very motivated to learn Chinese, within SG community Mandarin is the formal standard Chinese while most families speak a dialect at home

|

Generally yes, however many Dutch people speak English well and will switch in mixed groups

|

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Research summary on Language

_________________________________________________________________________________

Background Research

This study has presented the typical knowledge management dilemma – there is a considerable amount of information and research, both academic and practical but it is widely dispersed and personal experience is often not documented.

History

Most research into BML (bi- and multi-lingualism) concerns itself with assimilation of immigrants (Fillmore, 2000; Slavin, Madden, Calderon, Chamberlain, & Hennessy, 2011; Slavin et al., 2011; Winter, 1999); maintaining minority (or majority) languages in a dominant language environment (Ball, 2011; Dixon, Zhao, Quiroz, & Shin, 2012) or language immersion or bilingual programmes; (Caldas & Caron-Caldas, 2002; Carder, 2008; Cummins, 1998; Genesee, 2014; Hadi-Tabassum, 2004; Soderman, 2010) aspects of which may or may not be relevant to this study or its population.

Bilingualism

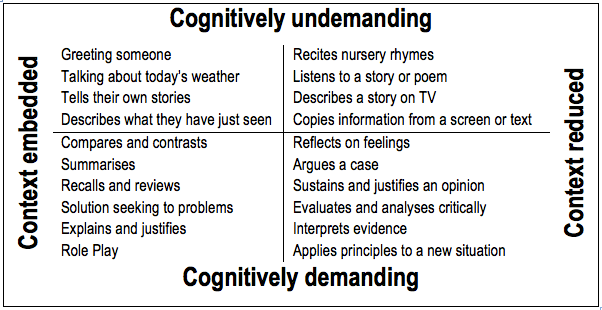

Researchers distinguish between three types of bilingualism. Simultaneous bilingualism – exposure to two languages from birth; early successive bilingualism – first exposure aged 1 – 3 years; and second language bilingualism – first exposure aged 4 – 10 years. There is considerable debate as to what exactly the “critical” ages are for successful language learning. As Kirsten Winter pointed out “Language learning is a continuum and bilingualism is not a perfect status to be achieved.” (Winter, 1999, p. 88). Typical language learners cycle through alternating stages of passive (receptive) and productive (expressive) skills, usually in the order of listening, speaking, reading and then writing.

Factors Impacting Acquisition

Researchers agree on a number of factors which impact on the successful acquisition and retention of a second or subsequent language in the BML population. These relate to the student, family, school and the community or society.

Student

Family

A large vocabulary in any language contributes to overall “oral proficiency, word reading ability, reading comprehension, and school achievement”(Dixon, Zhao, Quiroz, et al., 2012, p. 542). Vocabulary is influenced by the parent’s level of education, access to and availability of resources, and the quality and quantity of parent-child interactions, including shared reading, frequency of story telling and conversations.

School

The International school context results in a number of issues that complicate MT provision, including the multicultural and multilingual nature of the student population, resulting in ‘fictive monolingualism’ and the transience of both the student and teacher population, with the resultant socio-psychological implications on learning (Caldas & Caron-Caldas, 2002; Hacohen, 2012; Hornberger, 2003). However, where the “cultural capital” of the school included valuing language diversity in its environment and teaching practise, students had an increased sense of belonging, higher levels of reading literacy and they scored significantly higher academically. Continued development of ability in two or more languages on a daily basis resulted in a deeper understanding of language across contexts. Best practice includes a well structured MT program with at least some inclusion in the school timetable and fee structure, inclusion of other subject matter in MT lessons, support for English acquisition through a daily ESL/EAL program, a socio-culturally supportive environment, better awareness and training for subject teachers, affirmation of students’ identity as bi- or multi-lingual and collaboration with parents, while block scheduling was not optimal for language learning (Carder, 2014; IBO, 2011; Tramonte & Willms, 2010; Vienna International School, 2006; Wallinger, 2000). Research in heritage language (HL) teaching and learning indicates that macro-approaches and other specific strategies that build on learners’ existing language skills could be leveraged to improve reading and writing abilities, increase motivation and participation and validate students’ identity although specific teacher training for HL is recommended (Lee-Smith, 2011; Wu & Chang, 2010).

Community and Society

The support of a locally based language community, including faith and cultural communities had a positive impact which could mitigate socio-economic status (SES) factors and enhance learning through beliefs and practises, classes and cultural and religious activities (Dixon, Zhao, Quiroz, et al., 2012). Finally the availability of and access to learning resources, complementary schooling, books and other materials impacted on acquiring and maintaining language(Scheele, Leseman, & Mayo, 2010)

Concerns

Although the value of BML has become more widely accepted and most parents and educators appreciate and encourage the process, a number of concerns have rightly been voiced on the process and efficacy of reaching the goal of a BML child. In the first instance, the quality of the productive language – oral and or written skills – of one or all of the child’s languages may not develop to a sufficiently high level for academic or employment purposes (Cummins, 1998).

References:

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.