Introduction

There is a long history of research into the value of and elements contributing to the success of classroom libraries. They have an important role in ensuring accessibility of written works to promote fluency and skill in literacy and thereby contributing to academic achievement. But the literature appears to concentrate on elementary schools (Hopenwasser & Noel, 2014; James, 1923; Jones, 2006; Krarup, 1955; Powell, 1966; Sanacore & Palumbo, 2010; Todd, Gordon, & Lu, 2011; Worthy, 1996). Although partnership and collaboration with the school and/or public library and librarian is recommended, the literature often deals with the two spaces in isolation. Further, the problem of aliteracy in middle school – whereby students can read but don’t want to – is well documented (Kelley & Decker, 2009; Krashen, 2004; Lesesne, 1991; Sheldon & Davis, 2015; Worthy, 1996). This case report will show how the two environments library and classroom, can successfully be seen as extensions of each other through the principles of design and design thinking and explicit cooperation between the language humanities (Eng/Hum) teachers, literacy coach and school librarian in order to promote voluntary reading.

Case development

United World College South East Asia East (UWCSEA-East) is a K-12 international school located in Singapore. It commenced operations in 2008 and took occupancy of a purpose built campus in 2011. In this campus, the secondary school library initially served around 500 middle school students – see table 1. It now caters to three distinct communities, middle school, high school and the International Baccalaureate (IB) – see Table 2.

Despite consultation with the librarian in the planning phase, certain spaces of the library were designated different functions than agreed upon and furnished accordingly by the architect and building manager. One such area was upstairs overlooking the main school plaza with purpose built magazine racks. The idea was it would be a well-frequented showcase area for magazine reading. In reality a number of factors prevented this from being realised:

- The furniture design didn’t accommodate its purpose as it was not deep or high enough and the storage area didn’t fit back copies

- The zoning of the library post occupancy meant that materials affording quick casual reading such as graphic novels and periodicals were better located in the “noisier” and fast turnover area which allowed food and beverages, i.e. downstairs.

- The trend in libraries is to move away from physical magazines and periodicals towards online providers including online databases and aggregators such as PressReader that provide the same product at a lower cost and without delays and issues with cataloguing and maintenance.

The question of what to do with the space was resolved by noticing that as the secondary school reached post occupancy capacity the lowest students in the pecking order i.e. middle school students were increasingly marginalised with students of higher sections taking over the prime library real estate (students are visually distinct due to different coloured polo shirts for their uniforms). In addition, middle school students no longer had library visits planned into their schedule. Furthermore, the large influx of new students and teachers meant that reading books in the classrooms were unevenly distributed both in terms of volume and quality without any structured form of classroom library, which the students had become accustomed to in the primary section. Finally, Eng/Hum teachers were noticing a decline in voluntary reading as students moved up through middle school.

These issues were addressed initially through collaboration between the librarian and Eng/Hum teachers and more recently by the new literacy coach over a period of three years as follows:

- The conversion of the magazine area into a middle school reading zone

- The establishing of a core library for each of the three middle school grades (Day, 2013b)

- The creation of middle school classroom libraries in a formal and structured manner with materials integrated into the library catalogue (Day, 2015d)

- The integration of informational / nonfiction texts into both areas

This is an on-going process and worth a critical analysis to examine the choice process, latent or existing attitudes and assumptions, exterior pressures and design constraints and collaboration and communication.

Critical analysis

Choice of process

The spatial change in the library was conceived and led by the teacher-librarian (TL) with the Eng/Hum teachers joining in the collaboration as the process evolved. Since the TL has experience in design thinking (Day, 2013a, 2015a, 2015c) the process followed the design thinking cycle of inspiration, ideation, iteration and getting to scale (Brown, 2008; IDEO, 2014).

This was achieved by:

- Agreeing on a “core library” of 30 titles per grade for grades 6-8 which were prominently displayed

- Adjusting shelving to accommodate front facing books

- Relocating books of interest to this age group from the fiction collection

- Using large posters to highlight the favourite books of middle school teachers in the library and class corridors and classroom walls

- Ensuring multiple copies of books, by using class and literary circle sets

- Adequate lighting, comfortable furniture and the creation of a private space

The above steps and final spatial design incorporated the elements that are recommended as enhancing school library spaces (Cha & Kim, 2015; Elliott-Burns, 2003; La Marca, 2008; A. McDonald, 2006; Serafini, 2011).

The design elements that contribute to successful classroom libraries are not dissimilar and include:

- Sufficient space which is a focal area but partitioned and private

- Comfortable furniture

- Variety of material in range of complexity including different literary genres and informational texts

- Category organisation and shelf labelling

- Combination shelving allowing for quantity of books and display (front facing)

- Advertising by means of posters and notices on whiteboards

- Graphic organisation either thematic or by connections

- Involvement of students in selection, organisation and maintenance (Fractor, Woodruff, Martinez, & Teale, 1993; Hopenwasser & Noel, 2014; Reutzel & Fawson, 2002, cited in Sanacore & Palumbo, 2010)

Discussion and research on the elements predominantly come from the elementary school environment, and the adoption to middle school requires some adjustments to account for the fact that students do not remain in one classroom, lessening the sense of ownership of a space on the part of students, and teachers needing to cater to multiple classes with different profiles and interests. Learning spaces are also typically smaller relative to the size of the students.

The creation of the library and classroom reading spaces and populating them with books is “necessary but not sufficient” (McGill-franzen, Allington, Yokoi, & Brooks, 1999). Other components of encouraging reading include training teachers to enhance their instructional routines to incorporate the material, and to ensure that teachers are familiar not only with their literary canon, but also the latest in good young adult fiction (Day, 2015b; McGill-franzen et al., 1999). The school has invested in training with Penny Kittle to assist in the instructional routines (Raisdana, 2015), while the librarian is working with the teachers on the latter.

Latent or existing attitudes and assumptions

An international school is blessed with diversity in cultures, languages and backgrounds both of their students and teachers. This results in a context of people coming from different systems with different attitudes, assumptions, beliefs and experiences around education, reading and libraries. In just the middle school, teachers come from Australia, United States, Philippines, Ireland, Canada and the United Kingdom, each with their own literary core. In addition, there are personal preferences and beliefs, for example around young adult literature (see Raisdana, 2014). Teachers may not be used to or have experience of collaboration with the TL, the benefits thereof, nor aware of the ways in which libraries have evolved (Gibbs, 2003; Montiel-Overall, 2006, 2008; Sullivan-Macdonald, 2015). And naturally there are assumptions around what constitutes an ideal learning or reading space and the balance between the two (Elliott-Burns, 2005). In a meta-review of access to print and educational outcomes, Lindsay (2010) concluded that limiting choices with a larger distribution interval led to more reading, particularly if it was accompanied by activities such as training and book talks. This is in contrast to the assumption that collections should be as large as possible. It also suggests that rotation of materials leads to better outcomes.

Exterior pressures and design constraints

The creation of the complementary spaces faced a number of constraints, design and otherwise. These included a small budget, limited time and variability in the reading level of students. In design thinking the presence of constraints is seen as a positive force that encourages creative solutions and exploring options that would not otherwise be considered, and this proved to be true in this case study (Brown & Katz, 2011; Hill, 1998; Ness, 2011).

Naturally budget was an important constraint that shaped the way in which the space was converted and books and furniture was acquired or moved and repurposed. As discussed earlier, the librarian was involved in the “fuzzy front end” (Sanders & Stappers, 2008, p. 6), of the secondary library design and once the space was completed it was not possible to change the space, only to adapt its purpose. In the classrooms the availability of furniture in the room to hold the books and the available space for the classroom library vis-à-vis other learning spaces determined how many books could effectively by stored and displayed. In this respect creative design thinking was deployed, for example by taking the doors off built-in cupboard space both in the classrooms and in the library, creating additional shelving. Comfortable furniture was either acquired by donations from the community or purchased to ensure equity between the classrooms.

Although the library and classes each have a budget for the acquisition of books, both wanted to ensure that existing resources were not wasted – for example the books already owned in multiple copies. However their repurposing had to be examined within the constraints of the reading level of the students and the curriculum themes for each grade.

Collaboration and communication

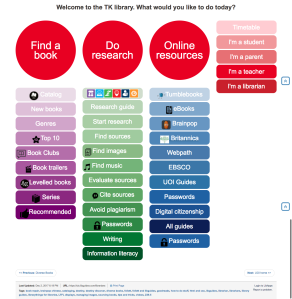

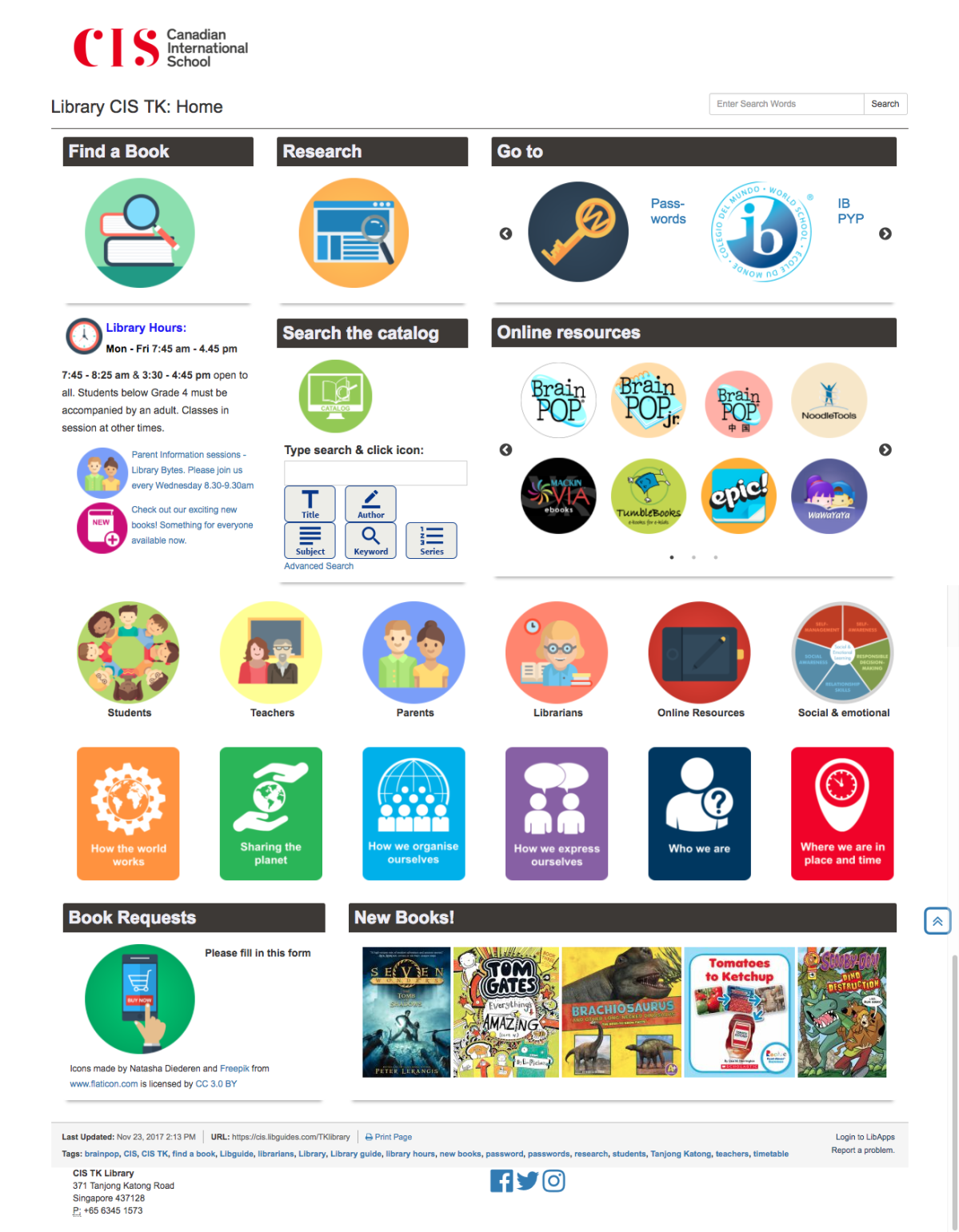

Collaboration and communication between the TL and teachers has received a lot of attention as has the ways in which spatial design and design thinking can enhance collaboration (Avallon & Schneider, 2013; Ferer, 2012; Gibbs, 2003; Knapp, 2014; Montiel-Overall, 2006; Williamson, Archibald, & McGregor, 2010). Enhancing collaboration between the TL and the Eng/Hum department has occurred on a number of fronts, both physical and virtual – such as book chat mornings to book talk new books, encouraging teachers and students to be involved with the selection of books for the Red Dot Awards (ISLN, 2015), processing and cataloguing the books, and the creation of a virtual space for the books (Day, 2015b).

Given time constraints and curriculum pressures, additional moments for collaboration and communication have had to be designed into the process. For example teachers can book the reading zone space to conduct lessons, and invite the TL to book talk new or noteworthy books. In addition the library receives supervision assistance from teachers during lunch, recess times and after school. The Eng/Hum teachers have first priority in requesting this duty, creating the opportunity for the important “casual conversations” that result in informal learning and information exchange (Oblinger, 2006; Somerville & Brown-Sica, 2011).

Conclusion

The process can neither be criticized for its efficacy nor results. Teachers, students and the librarian have largely viewed the change positively. Due to making small iterative changes to the spaces, starting with a small budget and a limited number of books in the first year, and subsequently adapting the choice of books, the selection and weeding process based on experience and feedback, the combined library / class library spaces appear to have grown organically despite a lot of “behind the scenes” work on book processing, cataloguing and making books classroom / shelf ready.

There are five main recommendations arising from the analysis of this case study, all which can be tackled through employing design thinking rather than further changes to the current spatial design:

- Balance the contradictory forces of novelty and familiarity through how books are selected, displayed and rotated

- Focus efforts on the most efficacious element of encouraging reading – book talks

- Expand the space to include the home environment, particularly in the case of bilingual students

- Increase involvement of students in the spatial design and change process

- Quantify the benefits of this spatial / design thinking collaboration through evidence based research.

These will be elaborated in the next section.

Recommendations

Balance novelty and familiarity

Students like and respond to novelty in display and a constant supply of “new” titles, they would also possibly benefit from choice limitation (Iyengar, 2011). This can be achieved by a rotation of titles between spine and front facing, and through a rotation between the books in the various classes (Lindsay, 2010). At present the core and class libraries are refreshed annually and the class libraries are not rotated between classes or teachers. It is recommended this be considered to prevent staleness. The class library placement of books in bins rather than shelves with a mixture of front and spine facing, allowing changes is display is not best practise, nor is having all books available simultaneously (Fractor et al., 1993; Lindsay, 2010; Sanacore, 2000; Sanacore & Palumbo, 2010).

Book talks

The importance of teachers’, librarians’, students’ and the community’s increasing exposure of diverse books in all genres by book talking can’t be overstated (Bentheim, 2013; Gallo, 2001; L. McDonald, 2013; Serafini, 2011). But, as examined in the analysis, a number of barriers stand in the way of regular book talks. In addition, requiring reading related tasks from students runs the risk of resulting in unfavourable associations with reading and further reluctance (Eriksson, 2002; Gallo, 2001; Miller, 2009).

Many practioners have described how digital innovation and the creation of virtual spaces can enhance and augment traditional book talks as well as expand transliteracy skills of students (Dreon, Kerper, & Landis, 2011; Gogan & Marcus, 2013; Gunter & Kenny, 2008; Ragan, 2012). It is recommended that students be given ownership of exploring the potentials of the digital realm in this respect as a guided design thinking exercise.

Mother tongue material and the home environment

Access to mother tongue materials continues to be a weakness in the library and even more so in the classroom library. There are logistical and financial constraints including the wide spread of languages, the undervaluation of low status languages, and misinformation and misunderstanding on the value of reading in the mother tongue amongst students and parents (Bailey, 2014a, 2014b, 2015; Boelens, Cherek, Tilke, & Bailey, 2015). This is an area that would benefit greatly from increased collaboration between the college and parent body where previously “unknowable” resources could be tapped into through utilizing the analytical and process skills of design thinking (IDEO, 2014; Landis, Umolu, & Mancha, 2010; McIntosh, 2015).

Student involvement

While literature indicates collaboration by all stakeholders is essential for acceptance, particularly in learning environments (Hamilton, 2013; Jones, 2006; Sanders & Stappers, 2008), this has largely been a librarian / teacher initiative with some student involvement in book selection. Moving forward, the virtual or digital sphere is an area where students can also be encouraged to carve out a presence and take ownership with teachers taking on an enabler role as use of all seven learning spaces are maximised (Grisham & Wolsey, 2006; McIntosh, 2010; Thornburg, 2007; Wilson & Randall, 2012).

Quantify the benefits

Despite numerous hurdles in providing data and making analysis founded on circulation figures or student attainment records, there is considerable value in documenting and providing evidence for practises – not the least that it supports budget requests.

Circulation records do not provide a complete record or necessarily correlate with reading because:

- Books may be read in library / class without being checked out

- In affluent multi-cultural communities, students may have access to large personal libraries, including books in their mother tongue

- Students may be borrowing books from the public library

Despite this, circulation is still the best proxy for reading. The decentralised nature of the class libraries results in less control over book checkout. Even in the library, that has no exit barriers, at the end of 2014/5 academic year roughly 20% of returned books had not been checked out of the system. While this can be lauded as an indication of the high moral and ethical standards of the students, it does pose difficulties in creating any evidence based data on the actual impact of either separating part of the library or decentralising the collection to class libraries in terms of increases in circulation.

It is recommended that both current and longitudinal research be carried out to see if there is any correlation between increased access to text, the amount of reading / circulation and other objective measures of attainment such as the annual PISA or TIMS tests. This will take the initiative beyond transformative individual anecdotal stories to evidence based research. The CLEP (Classroom Literacy Environmental Profile) (McGill-franzen et al., 1999; Wolfersberger, Reutzel, Sudweeks, & Fawson, 2004) and more recently the TEX-IN3 (Hoffman, Sailors, Duffy, & Beretvas, 2004) tools have successfully been used in the evaluation of elementary school class libraries and could be adapted for the middle school environment.

The recent inclusion of informational (nonfiction) texts in both the middle school zone and the classroom libraries is also one worth further investigation. Whether the expansion of the collections has impacted on the space, the ability to choose, and the completion of summative assessments in the individual subjects can be investigated in the light of the existing literature on the matter (Hopenwasser & Noel, 2014; Ness, 2011; Sanacore & Palumbo, 2010; Young & Moss, 2006; Young, Moss, & Cornwell, 2007).

References

Boelens, H., Cherek, J., Tilke, A., & Bailey, N. (2015). Communicating across cultures: cultural identity issues and the role of the multicultural, multilingual school library within the school community. Presented at the “The school library rocks” IASL 2015, Maastricht, Netherlands.

Dreon, O., Kerper, R. M., & Landis, J. (2011). Digital storytelling: A tool for teaching and learning in the YouTube generation. Middle School Journal, 42(5), 4–9.

Elliott-Burns, R. (2003). Space, place, design and the school library. Journal of the Australian School Library Association, 17(2).

Elliott-Burns, R. (2005). Designing spaces for learning and living in schools: perspectives of a flaneuse. Presented at the Australian Curriculum Studies Association Biennial Conference, Queensland, Australia: University of the Sunshine Coast. Retrieved from

http://eprints.qut.edu.au/4345/1/4345.pdfFractor, J. S., Woodruff, M. C., Martinez, M. G., & Teale, W. H. (1993). Let’s not miss opportunities to promote voluntary reading: Classroom libraries in the elementary school.

The Reading Teacher,

46(6), 476–484. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20201114Gogan, B., & Marcus, A. (2013). Lost in transliteracy – how to expand student learning across a variety of platforms. Knowledge Quest, 41(5), 40–45.

Grisham, D. L., & Wolsey, T. D. (2006). Recentering the middle school classroom as a vibrant learning community: Students, literacy, and technology intersect.

Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy,

49(8), 648–660.

http://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.49.8.2Gunter, G. A., & Kenny, R. F. (2008). Digital booktalk: Digital media for reluctant readers. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 8(1), 84–99.

Hill, A. M. (1998). Problem solving in real-life contexts: An alternative for design in technology education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 8, 203–220.

Hoffman, J., Sailors, M., Duffy, G., & Beretvas, S. N. (2004). The effective elementary classroom literacy environment: Examining the validity of the TEX-IN3 observation system.

Journal of Literacy Research,

36(3), 303–334.

http://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3603_3IDEO. (2014). Design thinking for libraries – a toolkit for patron-centered design (p. 121).

James, M. E. (1923). Use of classroom libraries to stimulate interest and speed in reading.

The Elementary School Journal,

23(8), 601–608.

http://doi.org/10.2307/994550Krashen, S. D. (2004). The power of reading: insights from the research. Westport, Conn.; Portsmouth, N.H.: Libraries Unlimited ; Heinemann.

Landis, D., Umolu, J., & Mancha, S. (2010). The power of language experience for cross-cultural reading and writing.

The Reading Teacher,

63(7), 580–589.

http://doi.org/10.1598/RT.63.7.5McDonald, L. (2013). Literature for children and young adolescents. In A literature companion for teachers (pp. 1–7). Newtown, Australia: Primary English Teaching Association Australia (PETAA).

McGill-franzen, A., Allington, R. L., Yokoi, L., & Brooks, G. (1999). Putting books in the classroom seems necessary but not sufficient.

The Journal of Educational Research,

93(2), 67–74.

http://doi.org/10.1080/00220679909597631Miller, D. (2009). The book whisperer: awakening the inner reader in every child (1st ed). San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass.

Oblinger, D. (2006). Learning spaces. Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE.

Ragan, M. (2012). Inspired technology, inspired readers – How book trailers foster a passion for reading. Access, March, 8–13.

Wolfersberger, M., Reutzel, D. R., Sudweeks, R., & Fawson, P. (2004). Developing and validating the Classroom Literacy Environmental Profile (CLEP): A tool for examining the “print richness” of early childhood and elementary classrooms.

Journal of Literacy Research,

36(2), 211–272.

http://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3602_4