Communicating across cultures: cultural identity issues and the role of the multicultural, multilingual school library within the school community

Dr. Helen Boelens

School Library Researcher and Consultant, The Netherlands

John M. Cherek Jr. MSc

Project Manager, Zorgboerderij “De Kweektuin”, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands

Dr. Anthony Tilke

Head of Library Services & TOK Teacher, United World College of South-East Asia (Dover Campus), Singapore

Nadine Bailey

United World College of South East Asia (East Campus), Singapore

Abstract

The arrival of increasing numbers of refugees and immigrants has caused large increases in multicultural school populations.This interdisciplinary paper describes an ongoing study which began in 2012, discussing the role of the school library in multicultural, multilingual school communities and offering suggestions about how the school library could become a multicultural learning environment. It provides information to help school library staff to look closely at these issues and to provide help and useful suggestions to the entire school community. The prime objective is to help the school community to safely and constructively deal with the dynamics of a multi-cultural society, using the school library as a base. Safe facilitation requires “trained” leaders from the school community. An e-learning program for school librarians is being adapted for this purpose.

Keywords: multi-culturalism, multi-lingualism, languages, cultural identity, global literacy.

Introduction

At the IASL Conference 2012, a paper discussed the role of the school library in multicultural, multilingual school communities and offered suggestions about how the school library could become a multicultural learning environment (Bloelens, van Dam and Tilke, 2012). Since 2012, various factors have affected multicultural school populations in many different types of primary and secondary schools in countries throughout the world.

Limitation of this study

This paper seeks to understand how learning experiences of multicultural, multilingual students can be accommodated in the school library. Boelens and Tilke (2015) recently described relevant trends and ideas which posits the role of the library in multicultural/lingual school communities from different areas of study: education and pedagogy, library and information science, psychology, sociology and anthropology, and linguistics.

Educational trends

Some international organisations have indicated educational trends. UNESCO’s statement on global education provides a set of objectives for international education until the year 2030. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recommended that schools support both “the identifiable needs of today, and the uncertain demands of the future” (OECD, 2005); schools should provide an environment that will support and enhance the learning process, encourage innovation, foster positive human relationships – in short, be “a tool for learning”. The term “learning environment” suggests place and space: a school, a classroom, a library. However, in today’s interconnected and technology-driven world, a learning environment can be virtual, online, remote – it doesn’t have to be a physical place at all. Perhaps a better way to think of 21st century learning environments is as support systems that organize the conditions in which humans learn. How does this affect the school library?

Library and information Science trends

How do these changes in educational theories and expectations affect the school library? Commentators in North America have suggested that the library has now become part of the school learning commons (Canadian Library Association, 2014; Loertscher et al, 2011; Loertscher et al, 2008). Educuase (2011) considers that learning or information commons

has evolved from a combination library and computer lab into a full-service learning, research, and project space. … In response to course assignments, which have taken a creative and often collaborative turn … learning commons provides areas for group meetings, tools to support creative efforts, and on-staff specialists to provide help as needed. The strength of the learning commons lies in the relationships it supports, whether these are student-to-student, student-to-faculty, student-to-staff, student-to-equipment, or student-to-information (p. 1)

Can the needs of multicultural/lingual learners be specifically supported in a Learning Commons environment? Osborne (2014, p. 7) states that “more and more schools … are committing to provide physical spaces that align with, promote and encourage, a more modern vision for learning” and asks “how might the library act as a ‘third place’ to provide unique, compelling and engaging experiences for staff, students and community that aren’t offered elsewhere?” (p. 8)

Furthermore, librarians are co-teachers within multicultural/lingual school communities (Medaille and Shannon, 2014); co-teachers are “two equally-qualified individuals who may or may not have the same area of expertise jointly delivering instruction to a group of students” (Curry School of Education, 2012).

Racial, Cultural and Ethnicity issues (Psychology, Sociology, and Anthropology)

Key factors are:

- Students cannot start learning until they feel safe, seen and valued;

- Learning is diminished and/or does not occur without addressing equity and diversity topics;

- Equity and diversity topics are intertwined with academic achievement.

This paper will also discuss subjects such as “diversity” and “difference” in multicultural situations within the school community and how these matters affect the school library, not only in developed countries, but also those which are located in emerging and developing countries (Boelens and Tilke, 2015, p. 2). Students from diverse cultural backgrounds, who differ from mainstream students in terms of ethnicity, socioeconomic status and primary language, are entering schools in growing numbers. The education which these students receive needs to address multicultural and intercultural issues. Intercultural education relates to culture, religion, cultural diversity and cultural heritage and respects the cultural identity of learners through the provision of culturally appropriate and responsive education, which focuses on key issues and interrelationships (UNESCO, 2006). It concerns the learning environment as a whole and impacts many different aspects of the educational processes, such as school life and decision making, teacher education and training, curricula, languages of instruction, teaching methods, student interactions and learning materials. (UNESCO, 2003a)

Language acquisition

Based on international research, practice and comment, Della Chiesa, Scott and Hinton (2012) identified strong connection between language and culture(s), looking for future benefits in human endeavour, partly as a result of recognizing that language acquisition and use does not develop in isolation from socio-cultural and indeed brain development. International understanding is perceived as a desired social outcome of such interventions.

Features of language learning assist teachers of culturally and linguistically diverse students. Learners learn a language best when treated as individuals, experience authentic activities in communication in the target language and see teaching as relevant to their needs. Learning should be relevant to their needs and they benefit from seeing strong links between language and culture. They also benefit from having helpful feedback on their progress and where they can manage their own learning. (Vale, Scarino and McKay, 1991)

Background information

Demographic shifts, i.e. changes in the demo-linguistic situation, have taken place. Children from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, including immigrant and refugee children, are entering schools all over the world; changing demographics will alter both school practices and policies (Center for Public Education, 2012). Features of experiences for students in various countries include:

Culturally and linguistically diverse students in Australia typically come from a wide range of language, socio-economic, cultural and religious backgrounds. Up to one-fifth of such students are newly arrived in Australia and with a language background other than English; even if some students are born in Australia, they may enter the school system with little or no English language. (Department of Education of Western Australia, 2011). Australian schools may experience large populations of immigrant and/or refugee students (Ho, 2011).

There were similar issues in Canada, where students did not have language skills in the main languages used for teaching and learning, though differences in educational performance reduced as students progressed through the school system (Statistics Canada, 2001).

The United Kingdom too experienced similar issues, where a focus on educating significant numbers of students who spoke English as an additional language (EAL) (British Council, 2014).

Looking at countries where English is not the main or major language of teaching and learning, the European Commission (2015) reported very similar issues for schools and for students, not least for asylum seekers.

The USA too has seen changing demographics in schools. Forty-seven percent of children younger than five belong to a racial or ethnic minority group, and “trends in immigration and birth rates indicate that soon there will be no majority racial or ethnic group in the United States” (Center for Public Education, 2012). Implications for such trends may include needs for qualified bilingual teachers, preschool programmes, concerns over drop-out rates from mainstream education, and other resource issues in schools.

Important identity issues in the context of the school community

This paper posits that the school library must be a safe space that welcomes all questions, perspectives and backgrounds. School libraries offer valuable resources (in both traditional and digital format), information, knowledge and insight. In a school context, a library space is one where students can explore their ideas and ask questions. Librarians provide specialised support within this domain and have a responsibility to support the growth of their students. Such healthy development of students can have a strong impact on self-esteem, academic performance and feelings of cohesion. In a multi-cultural school setting, issues of race, ethnicity and culture play a central role in the identity of the school and its students. Celebrating our differences is one way of acknowledging the diverse backgrounds of members of the school community, though such diversity can be overshadowed by a dominant culture and its narrative.

As professionals in education, it is our responsibility to develop competence in the areas that matter to our students, including our own understanding of race, culture and ethnicity, to ensure that young people receive targeted guidance and support they need in order to explore a healthy sense of self.

Identity

Central to identity formation is the “challenge of preserving one’s sense of personal continuity over time, of establishing a sense of sameness of oneself, despite the necessary changes that one must undergo in terms of redefining the self” (Harter, 1990). Adolescence is an important and formative period in life that influences many parts of identity development (sexual, racial, ethnic, gender, etc.). Identity development is a dynamic process that plays a central role in developing our relationship to the self, the other and our social environment. It is especially during adolescence that we play around with multiple identities, experiment with “the rules” and test the institutions around us. As a result of this process, parts of our identity are kept and nurtured, while others are briefly worn and discarded.

Much research about racial and ethnic identity development has focused on adolescent and college age individuals. (Helms (1990) in Phinney, 2007, p. 275) This makes sense because self-reflection is an important part of collecting data. It does not necessarily imply that younger children do not have the ability to reflect, but their process of reflection may be different. For example, younger children tend to describe themselves in a more simple, less sophisticated way, according to their perception of personality characteristics — “I am nice”/ “I like to make other people feel good”/ “I like to help people”. This is less about their relationship to things (toys, food) and more about their understanding of certain qualities (both good and bad). For example, “I am good at writing and bad at soccer”. This relates to ethnic identity development, when children become aware of good and bad qualities about their ethnic group. Understanding why society deems these certain qualities good or bad is perhaps one way to help prepare them for dealing with a multi-cultural environment with dominant ideas that are not their own. Ethnic identity has been studied largely with reference to one’s sense of belonging to an ethnic group, that is, a group defined by one’s cultural heritage, including values, traditions, and often language (Phinney 2007, p. 274). Finding interactive and “fun” ways to help children explore or even explain their understanding of these things is one role the school library can play; by facilitating access to information, librarians can guide students through relevant books, movies and other multimedia tools.

Adolescence is a developmental stage between childhood and adulthood when individuals experience biological, social and psychological change. According to psychoanalyst Erik Erikson (1968), ego identity versus role confusion. It is the psychosocial stage of personality development that adolescents encounter when faced with the question, “Who am I?”. A healthy resolution of this stage can lead to strong ego identity. Unhealthy resolution of this stage will contribute to role confusion. Role confusion challenges our ability to build connections and participate as members of society. Here, adolescents create and recreate meaning to provide themselves with a sense of connection. When a lack of connection exists, the ego struggles to build a foundation for fidelity, based on loyalty. If adolescents lack fidelity, they might encounter, in extreme cases, a future of social pathology, crime and prejudicial ideologies. These negative characteristics can manifest when the individual participates as an adult, for example, in religious, athletic, national, and military rites and ceremonies (Engler, 2014).

Racial, Cultural and Ethnic Identity

A healthy racial and ethnic identity can help youth establish a consistent view of themselves. Many aspects of adolescence are transient and changing. One day we love the color yellow and the next day it is the color red. Thus, by creating a permanent anchor from which to develop, we give our students a better chance at achieving positive outcomes; without these anchors, many young people may identify with a completely different culture which has nothing to do with “who they are”.

Identity issues and their importance in the school and the school library

The feeling of belonging is critical to every child’s well-being and helps him/her to fulfill his potential in many different areas of development: physical, social, emotional and cognitive (Welcoming Schools Childhood Education Program, 2015).

Cherek’s 2015 research is concerned with ways that students can develop a healthy racial and ethnic identity and improve their understanding and vocabulary around race and ethnicity, therefore contributing to increased cultural competence; this contributes to higher self-esteem and healthy development. By using these essential skills, students have the opportunity to take ownership over their ideas and are encouraged to examine the world around them — at home, school, work and in the media – thus preparing them to thrive in multicultural environments.

Essentially, children who feel good about themselves may be more successful, not only at school but in different aspects of their lives (Tough, 2012). Identity is not something that individuals automatically have. Identity develops over time, beginning in childhood, through a process of “reflection and observation” (Erikson 1968, p. 22) Important questions to ask about a child’s learning environment is does he/she see other teachers, parents or students in the school who represent his/her own culture or heritage? Who do these children identify with? Who do they see as a reflection of themselves, e.g. public figures?

Using these factors, the school library becomes a safe “public” space where a healthy and proactive sense of diversity encourages deep and meaningful conversations with all members of the school community about stereotypes such as discrimination and racism.

Involvement of the school library/ian in multicultural, multilingual education

Ultimately, the aim is that students, teachers and librarians are prepared to safely and constructively deal with the dynamics of a multi-cultural society. Safe facilitation requires “trained” leaders from the school community.

In larger schools with academic disciplinary silos, it may be difficult to create positive messages about mother tongue and cultural identity and pride across to members of the school community as a whole – school leaders, teachers, students and parents. The EAL (English as an Additional Language) teacher is most concerned about getting the students up to speed and may inadvertently give the wrong message. The teaching of the student’s (minority) language may not be part of the school language policy.

The Welcoming Schools Childhood Education Program (2015) suggests that children who are motivated and engaged in leaning are more committed to the school. By providing books, information and other resources, the library can “provide an important mirror for children to see themselves reflected in the world around them”. Here, library resources “also provide a window to the lives of others. … [and] students also find positive role models through literature”; benefits from such activities are best seen when coordinated in the school community. The library can provide a stable permanent base for the length of the student’s school career.

Research (Bedore and Peña, 2008) indicates that bilingualism can only be sustained if there is at least a 30% input in the less dominant language. If the less dominant language is not a language which is used and taught within the school community, then the library can provide access to relevant materials. This is an intellectual process of proving the benefit and a practical exercise of resource collection, curation, access, promotion and marketing. These can be very simple, such as the creation of displays of books about diversity, multiculturalism and multilingualism and about national days of the countries which are represented by children at the school, and reflecting their cultures.

In any event, the school library is a helpful environment where students can reflect on these issues. It can highlight resources, or profile individuals relevent to various ethnic groups. This can be achieved by exploring literature authored by individuals from their ethnic own group or by reading about the history of their own ethnic group. Additionally, the library can give students the basic skills to find or locate this information.

Multicultural, multilingual school libraries

In 2012, Boelens, van Dam and Tilke focused on various aspects of multicultural and intercultural education, identifying a symbiotic relationship with school libraries. It reported on support needs for both children who were immigrants, i.e. those permanently moving from one country to another, as well as more geo-mobile children, known as Third Culture Kids or Global Nomads. Various relational features were identified: literacy, language, bilingual education, world languages.

Krashen and Bland (2014) have identified the need for second language learners to develop competencies in academic language acquisition. Before that, self-selected recreational reading habits were partly dependent on a varied, indeed wide, selection of reading matter. In itself, this reading matter did not provide access to academic language acquisition, but it prepared children to do so. This reading stamina also had an effective domain, in that it motivated students to become readers, and arguably gave them confidence. For some children who use school libraries in multicultural education environments, the digital age was not wholly relevant, as ebook use was associated with affluence. For children whose socio-economic experience is that of poverty, libraries represent the only stable source of access to reading materials, especially in developing and emerging countries. The provision, promotion and use of such reading materials is a feature of the work of (school) libraries/ians in these countries. These libraries/ians support students and teach them to to navigate abundant sources of information. Such skills and aptitudes are commonly known as information literacy skills. Sometimes, the prevalence of information literacy skills is perceived as being a main role of the school library/ian, however the teaching of these skills and the provision of reading materials need to be symbiotically linked.

Smallwood and Becnel (2012) identified various factors in successfully providing library services in multicultural settings – accessing and reaching the clientele; provision of appropriate materials; consideration of use of space; focusing services on linguistic and socio-economic needs; appropriate technology; professional development and awareness-raising amongst school librarians. Indeed, Welch (2011) promoted the idea of the library collection having an aim of influencing student behavior, in terms of increasing tolerance and sensitivity in a multicultural setting.

Whilst not substantially different from good practice elsewhere, the International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO or IB) has identified good practice in library support for multilingual learning environments (International Baccalaureate, 2012). Schools that offer IB programmes comprise state or government schools, semi-independent, independent and international schools. When a school adopts IB programmes, it needs to also take ownership of IB philosophy, including a holistic approach to language and international-mindedness (Singh and Qu, 2013). There is, therefore, a symbiotic link between language and intercultural education approaches in schools which may (or should) experience strong ESL (English as a Second Language) support (Carder, 2014), though the IB stance is that every teacher is a teacher of language (International Baccalaureate, 2011).

Therefore, the literature has identified a need to develop competencies in academic language proficiency and a resource/information role for (both public and school) libraries, especially for children, sometimes immigrants or refugees, who are affected by poverty. Therefore, libraries may be part of scaffolding strategies to support children who need language support, and which include resources and facilities (space). Thinking and planning for such library services and support needs to be holistic and wide-ranging (from facilities and plant to professional development), all based on an understanding of the needs and concerns of targeted client groups.

Focussing services on the needs of multicultural/ingual students

The librarian needs to establish the current and future users of the school and its library, and user demographics (i.e. how many students come from which minority or language group). Library collection and services should then be related to such information.

School libraries have roles related to literacy and reading, and teaching and learning of information literacy skills. To support this, resources – mainly physical – have been curated to serve a mainstream interpretation of students’ needs, often curricular, and in the dominant language (often English). This role could be broadened to meet the needs of the multicultural/lingual school community.

- The library collection should contain books and information (in traditional and digital format) which reflect the diversity of the children in the school. The library exposes the entire school community to many different cultures and languages. This collection can help students to understand that while their families are unique, they share many common values, beliefs and traditions.

- The collection should contain literature in the native language of students, and link to digital international children’s libraries and also digital libraries for children from relatively small indigenous groups. This could include online links to songs, poems and stories from many different cultures and in many different languages. It should also contain current information about student countries of origin. Parents could be asked to help the librarian with this task. (Smallwood and Becnel, 2012)

Using these guidelines, the school librarian can strengthen the collection, and then present this information in attractive ways to the entire school community, so that it becomes aware of the extent of their library’s resources.

Librarians can provide an enabling portal function for immigrant, refugee and Third Culture Kids. They may be hesitant to assume this role, perhaps due to mono-lingual experience or lack of expertise in the creation of digital personal learning environments (PLEs) or personal learning networks (PLNs).

The librarian may consider applying principles of information ecology to the school library. This multi-disciplinary emerging field offers a framework within which to analyse the relationships between organisations, information technology and information objects in a context whereby the human, information technology and social information environment is in harmony (Candela et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2015).

Steinerová (2011) and Candela et al., (2007) looked at features of digital libraries and suggested that librarians examine where value integration can take place between the library service, technology, scholarship and culture, adding value through new services or contributions to learning, user experience, research productivity, teaching or presenting and preserving cultural heritage. Applying these ideas to the school environment, constituents of the eco-system include teachers, teacher librarians, students administration, parents and custodial staff (Perrault, 2007). Elements of the system will co-exist but also compete and share, converge and diverge in a dynamic interactive, complex environment (García‐Marco, 2011). The role of the library is such that information ecology needs to be understood in order to support information-seeking behaviour and thereby discover zones of intervention and areas to leverage to optimise advance information-seeking, usage, creation and dissemination within that eco-system and beyond. In response, curriculum, content and subject delivery can be collaboratively reshaped and constructed according to changes in the environment or needs of students (O’Connell, 2014).

Different kinds of resources and adaptive technologies can optimally support students with special educational needs (Perrault, 2010, 2011; Perrault & Levesque, 2012). This type of thinking can be adapted to considering the needs of bi- and multi-lingual students who are part of the school’s information ecology, but have linguistic and cultural learning and informational needs. These can be seen as a potential zone of intervention for collaboration between the teacher, teacher librarian (TL), family and community.

Literature intended for school librarians generally discusses cultural diversity in materials and the building of a world literature collection in response to student diversity or as part of language and humanities curricula (Garrison, Forest, & Kimmel, 2014). Some schools build a “Languages other than English” (LOTE) collection. To do so, schools may try to recruit bilingual or minority TLs or ask for help from parents; schools can also provide training in competencies in multicultural education (Colbert-Lewis & Colbert-Lewis, 2013; Everhart, Mardis, & Johnston, 2010; Mestre, 2009).

The main educational and social issues within schools are to ensure students acquire the official language of instruction so that they can adapt to the new learning environment without loss of educational momentum, while maintaining and developing their mother tongue (Kim and Mizuishi, 2014). Carder (2007) and Cummins (2001; 2003) suggest that even though there is evidence that supports the maintenance of mother tongue (the most effective way of supporting such students), schools place most effort and resources on the official language of instruction of the school. Evidence now presented above suggests that by doing so, children may lose some of their own healthy cultural and ethnic identity.

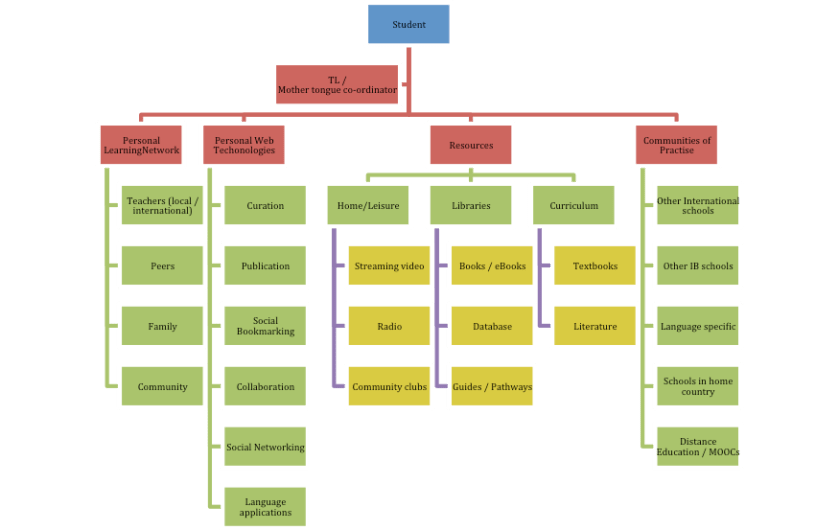

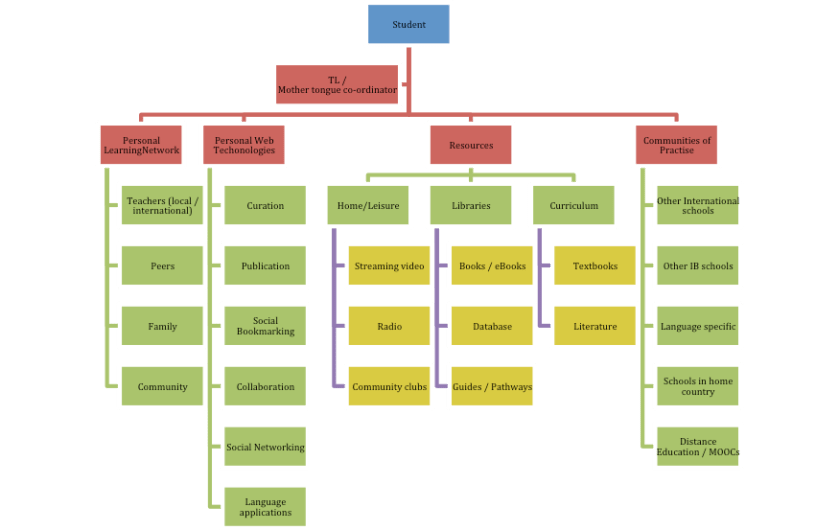

School librarians may be aware of geographically dispersed personal learning networks (PLNs) in order to create a personal learning environment (PLE) using various technological tools (McElvaney & Berge, 2009; O’Connell, 2014), and could assist different individuals throughout the school community to make use of a PLE. For instance, the International Baccalaureate (IB) allows students the option of guided mother tongue self-study if the school does not teach that specific language. Figure 1 below describes a PLE of an IB self-taught language student.

Figure 1: PLE of an IB self-taught language student

A training program about multicultural/lingual issues for the school community

In 2015, Boelens and Cherek examined the possibility of creating a personal development training program for the entire school community, facilitated by the school library. This is an attempt to help teachers, school leaders, librarians and parents to better understand problems being confronted by the multicultural/lingual school community, especially immigrants and refugees. This program would be made available through the school’s electronic learning environment.

The first part is a 24-minute video that provides an open conversation about race and ethnicity between professionals and young people. Here, participants listen to different perspectives about race and ethnicity, and appreciate why these topics are important to both caregivers (teachers, social workers, child welfare professionals) and young people. Finally, with the help of a study guide, participants explore the possibility of integrating racial and ethnic identity development into daily practice.

The second part is an eLearning course that provides participants with necessary tools to develop a deeper understanding of issues related to racism and discrimination. The content is specifically designed so that professionals (adults, educators, caretakers) develop a vocabulary for discussing race and ethnicity with others who are interested in and concerned about these subjects. A constructive vocabulary is an essential tool when discussing identity development, as it enables participants to safely address issues of racism and discrimination. Finally, participants can further integrate this deepened knowledge into daily practice. This is an important part of the training because it prepares participants for a facilitated in-person learning event.

The third and final part of the curriculum is a two-day in-person learning event. In this face-to-face meeting, trained facilitator’s guide participants as they begin to incorporate their new skills into daily practice. The most effective and powerful events occur when both young people and professionals are present. The training is highly interactive and challenging. Participants are encouraged to openly discuss the impact of stereotypes and the social influences that affect their own racial and ethnic identity.

A similar training program is by The Welcoming Schools Childhood Education Program (2015), which provides a starter kit for a personal development training programme for members of the school community, relating to equity, school climate and academic achievement.

Tapping into the experiences and communities of practise (COP) of distance education, massive open online courses (MOOCs), school librarians could be trained to facilitate this training program through PLNs and PLEs, Training programs would be available at any time and in any geographic location providing internet access is available. Initially, a pilot program would be tested with one language group, and could later be extended to other groups.

This training program will help to establish a multicultural/lingual school community based not only on academic achievement but also on a healthy climate with regard tp racial, cultural and ethnicity issues. It will also contribute to a school´s goals of equity in teaching and will require the support and involvement of the entire school community. Since library staff will be facilitating this program, their reputation will be enhanced, and be perceived as integral members of the school community.

Conclusion

This paper has discussed a developing role for the school library in the multicultural/lingual school community in 2015. It promotes a training program for the entire school community which will be facilitated by the librarian. Because of their involvement in the school´s learning commons, the librarian is already involved in interdisciplinary activities related to the multicultural/lingual nature of the entire school.

While all aspects of identity development are valuable, one area that is often ignored, especially when talking about young people who are detached from their culture, is racial and ethnic identity. Along with ever-changing realities of society, demographics and politics, the impact of race and ethnicity have never been more important.

With an increasing number of migrant and immigrant students, the acute reality of living in multiple worlds becomes more apparent. Social norms and values become entangled. Home life, school life and street life compete for attention. Without proper guidance and support, alienation that occurs when individuals feel split between dissonant forces results in a confused sense of “Who am I?”. Addressing these issues in an educational setting means that we as educators have the power to create “safe spaces” for our captive student audience. Thus, students can be prepared to effectively deal with the realities of a multi-cultural society while at the same time developing a healthy sense of racial and ethnic identity.

As a result of the proposed training program, students at the school will learn more about `who they are`, especially those who come from an immigrant or refugee background. With the support of the entire school staff, they will some to terms with their own cultural identity and ethnicity in their new school and in their new place of residence, and have positive feelings, with an expected corollary that their academic achievement will increase.

References

Bedore, L. M. and Peña, E. D. (2008). ‘Assessment of Bilingual Children for Identification of Language Impairment: Current Findings and Implications for Practice’, International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 11(1), 1–29. doi: 10.2167/beb392.0.

Boelens,H. van Dam, H. and Tilke, A. (2012). School Libraries across cultures. Presented during the Research Forum of the 2012 IASL (International Association of School Librarianship) in Qatar.

Boelens, H. and Tilke, A. (2015). The role of school libraries in our multicultural, multilingual society. Submitted for publication to the CLELE (Children’s Literature in English Language Education) Journal, in March, 2015. Not yet published. Munster, Germany: CLELE.

Boelens, H. and Cherek, J. (2015). Education 2030 (EU), and Onderwijs 2032 and Excellent Education in the Netherlands: a vision of the role of the multicultural, multilingual school library within these concepts. To be presented during the IASL (International Association of School Librarianship) 2015 Conference in Maastricht.

British Council. (2014). How can UK schools support young children learning English? Retrieved from http://www.britishcouncil.org/blog/how-uk-schools-support-young-learners-english.

Canadian Library Association (2014). Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada. Ottawa, On., Canada: Canadian Library Association. Retrieved from http://clatoolbox.ca/casl/slic/llsop.html

Candela, L., Castlli, D., Pagano, P., Thano, C., Ioannielis, Y., Koutrika, G., Ross, S., Schek, H-J., and Schuldt, H. (2007). Setting the Foundations of Digital Libraries: The DELOS Manifesto. D-Lib Magazine, 13 (3-4). Retrieved from http://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/157227

Carder, M. (2007). Bilingualism in international schools: a model for enriching language education. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Carder, M. (2014). Tracing the path of ESL provision in international schools over the last four decades. Part 1. International Schools Journal, 34 (1), 85-96.

Center for Public Education. (2012). The United States of education: The changing demographics of the United States and their schools. Retrieved from http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/You-May-Also-Be-Interested-In-landing-page-level/Organizing-a-School-YMABI/The-United-States-of-education-The-changing-demographics-of-the-United-States-and-their-schools.html

Colbert-Lewis, D., & Colbert-Lewis, S. (2013). The Role of Teacher-Librarians in Encouraging Library Use by Multicultural Patrons. In C. Smallwood & K. Becnel (Eds.), Library services for multicultural patrons: strategies to encourage library use (pp. 73–81). Lanham, MA: The Scarecrow Press.

Cummins, J. (2001). Bilingual Children’s Mother Tongue: Why Is It Important for Education? Retrieved from http://iteachilearn.org/cummins/mother.htm

Cummins, J. (2003). Putting Language Proficiency in Its Place: Responding to Critiques of the Conversational – Academic Language Distinction. Retrieved from http://iteachilearn.org/cummins/converacademlangdisti.html

Curry School of Education, (2012). Co-teaching defined. Retrieved from http://faculty.virginia.edu/coteaching/definition.html

Della Chiesa, B., Scott, J., and Hinton, C. (2012). Language in a global world: learning for better cultural understanding. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Department of Education, Western Australia (2011). Gifted and talented: Developing the talents of gifted children. Retrieved from http://www.det.wa.edu.au/curriculumsupport/giftedandtalented/detcms/navigation/identification-provision-inclusivity-monitoring-and-assessment/inclusivity/culturally-and-linguistically-diverse-background/

Educause Learning Initiative (2011). Seven things you should know about the Modern Learning Commons. Retrieved from https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eli7071.pdf

Engler, B. (2013). Personality theories : An introduction. 9th ed. London: Cengage Learning.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis.New York: Norton.

European Commission, Eurostat. (2015). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/help/support

Everhart, N., Mardis, M. A., & Johnston, M. P. (2010). Diversity Challenge Resilience: School Libraries in Action. In Proceedings of the 12th Biennial School Library Association of Queensland. Brisbane, Australia: IASL.

Garcia-Marco, F- J. (2011). “Libraries in the digital ecology: reflections and trends”, The Electronic Library, 29(1), 105–120.

Garrison, K. L., Forest, D. E., & Kimmel, S. C. (2014). Curation in Translation: Promoting Global Citizenship through Literature. School Libraries Worldwide, 20(1), 70–96.

Harter, S. (1990). Self and identity development. In S. S. Feldman & G. R. Elliott (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 352–387). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harter, S. (2012). The construction of the self : developmental and sociocultural foundations. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y.: Guilford Press.

Helms, J. (1990). Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice.New York: Greenwood Press.

Ho, C. (2011). “My School” and others: Segregation and white flight. Australian Review of Public Affairs, 10(1). Retrieved from http://www.australianreview.net/digest/2011/05/ho.html

Horsley, A. (2011b). Acquiring languages. In G. Walker (Ed.), The changing face of international education: challenges for the IB (pp. 54-69). Cardiff, UK: International Baccalaureate Organization.

International Baccalaureate. (2011). Language and learning in IB programmes. Cardiff, UK: International Baccalaureate Organization.

International Baccalaureate. (2012). An IB educator’s story about the role of librarians in multilingual learning communities. International Baccalaureate Organization. Retrieved from http://www.isgr.se/nn13/pdf/Roleoflibrarians.pdf

Kim, M., & Mizuishi, K. (2014, December 10). Language and Cultural Differences and Barriers in an International School Setting – Personal Experiences and Reflections [Presentation]. UWCSEA-East.

Krashen, S., & Bland, M. (2014) Compelling comprehensive input, academic language and school libraries. Children’s Literature in English Language Education (CLELE) Journal, 2(2). Retrieved 8 March 2015 from http://clelejournal.org/article-1-2/

Loertscher, D et al. (2008). The New Learning Commons: Where Learners Win! Salt Lake City, UT: Hi Willow Research and Publishing.

Loertscher, D et al. (2011). The New Learning Commons: Where Learners Win! 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Hi Willow Research and Publishing.

McElvaney, J., & Berge, Z. (2009). Weaving a Personal Web: Using online technologies to create customized, connected, and dynamic learning environments. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 35(2). Retrieved from http://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/viewArticle/524/257

Medaille, A. and Shannon, A. (2014). Co-Teaching Relationships among Librarians and Other Information Professionals. Collaborative Librarianship, 6(4).

Mestre, L. (2009). Culturally responsive instruction for teacher-librarians. Teacher Librarian, 36(3), 8–12.

O’Connell, J. (2014). Researcher’s Perspective: Is Teacher Librarianship in Crisis in Digital Environments? An Australian Perspective. School Libraries Worldwide, 20(1), 1–19.

OECD, (2005) Design. As cited in Pink, Daniel. (2005). A Whole New Mind. New York: Riverhead. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2001). Designs for Learning. Paris: OECD.

Osborne, M. (2014). Modern learning environments and libraries. Collected, SLANZA Magazine, 12. Wellington, New Zealand: The School Library Association of New Zealand Aotearoa Te Puna Whare Mātauranga a Kura (SLANZA). Retrieved from http://www.slanza.org.nz/uploads/9/7/5/5/9755821/collected_june_2014.pdf

Perrault, A. M. (2007). The School as an Information Ecology: A Framework for Studying Changes in Information Use. School Libraries Worldwide, 13(2), 49–62. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=28746579&site=ehost-live

Perrault, A. M. (2010). Reaching All Learners: Understanding and Leveraging Points of Intersection for School Librarians and Special Education Teachers. School Library Media Research, 13, 1–10. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=67740987&site=ehost-live

Perrault, A. M. (2011). Rethinking School Libraries: Beyond Access to Empowerment. Knowledge Quest, 39(3), 6–7. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=58621336&site=ehost-live

Perrault, A. M., & Levesque, A. M. (2012). Caring for all students. Knowledge Quest, 40(5), 16–17. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=82564002&site=ehost-live

Phinney, J., and Ong, A. (2007). Conceptualization and Measurement of Ethnic Identity: Current Status and Future Direction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3) 271–281.

Singh, M. and Qi, J. (2013). 21st century international mindedness: An exploratory study of its conceptualisation and assessment. South Penrith: Centre for Educational Research, School of Education, University of Western Sydney. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/contentassets/ 2470e1b3d2dc4b8281649bc45b52a00f/singhqiibreport27julyfinalversion.pdf.

Smallwood, C., and Becnel, K. (2012). Library services for multicultural patrons: strategies to encourage library use. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

Statistics Canada (2001) School Performance of Children of Immigrants in Canada 1994-98, Statistics Canada catalogue number 11F0019MIE2001178. Retrieved from http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/olc-cel/olc.action?objId=11F0019M2001178&objType=46&lang=en&limit=0

Steinerová, J. (2011). Slovak Republic: Information Ecology of Digital Libraries. Uncommon Culture, 2(1), 150–157. Retrieved from http://pear.accc.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/UC/article/view/4081

The Welcoming Schools Childhood Education Programs (2015). Actions You Can Take as a Librarian. Retrieved from http://www.welcomingschools.org/pages/steps-you-can-take-as-a-librarian

Tough, P. M. (2012). How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character. United States: Tantor Media.

UNESCO. (2003). Education in a Multilingual World, UNESCO Education Position Paper. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001297/129728e.pdf

UNESCO, (2006). UNESCO Guidelines on Intercultural Education, Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001478/147878e.pdf

Vale, D., Scarino, A. and McKay, P. (1991). Pocket ALL: A user’s guide to the teaching of languages and ESL. Carlton, Vic. : Curriculum Corp.

Wang, X., Guo, Y., Yang, M., Chen, Y., & Zhang, W. (2015). Information ecology research: past, present, and future. Information Technology and Management, 1–13. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-015-0219-3

Welch, R. (2011). Multiculturalism in school libraries. Warrensburg: University of Central Missouri.

Biographical notes

Helen Boelens (PhD) was awarded a Ph.D. degree by Middlesex University, School of Arts and Education in 2010. She now focuses her work on the development of and assistance to hundreds of thousands of school libraries in developing countries. She is the former co-ordinator of the Research SIG of the IASL (International Association of School Librarianship). She is also one of the founders of the ENSIL Foundation (Stitching ENSIL).

John Martin Cherek Jr. (MSc) received a Master’s in Political Science from the University of Amsterdam in 2009. His thesis examined the post-reintegration needs of former child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Before moving to Amsterdam to study at the UvA, John worked Casey Family Programs. As the largest operating foundation the U.S.A dedicated to improving outcomes for children in foster care, John developed programs related to life skills education, identity development and child welfare policy. Originally from the United States, John holds a degree in Psychology from Seattle University (2004). He works primarily with vulnerable populations and specializes in education, mental health and youth & child development.

Anthony Tilke (PhD) has spent nearly 20 years in the international school sector, in Asia and Europe. His doctoral thesis (from Charles Sturt University, Australia) focused on the impact of an international school library on the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Programme, and which subsequently fed into his book about the Diploma and the school library/ian. A common feature of his work is supporting mother tongue programmes in schools, and he has contributed to an IB document “An IB educator’s story about the role of librarians in multilingual learning communities”.

Nadine Bailey (M Phil, MBA, MIS) has lived and worked internationally for 20 years, in Africa, South America, Europe and Asia. Her area of interest lies in language and identity particularly related to students educated in a third culture environment. In an increasingly digitised educational environment she argues that librarians play an important curation and leadership role in guiding and enabling students to create personal learning networks in and for their mother tongue language. In that way libraries are both a safe physical and virtual space.

pt a marking rubric template to fit your assessment. Broadcast your question as widely as possible. Start a conversation about your topic somewhere on social media. Create a twitter storm. Kill a current holy cow. Go against the goose-stepping flow. Engage a segment of the education community – either in the traditional hug fest or having them flame you down. But DO something.

pt a marking rubric template to fit your assessment. Broadcast your question as widely as possible. Start a conversation about your topic somewhere on social media. Create a twitter storm. Kill a current holy cow. Go against the goose-stepping flow. Engage a segment of the education community – either in the traditional hug fest or having them flame you down. But DO something.