At times people will write to me and ask about things in library-land where they assume that somehow I or the (highly regarded) school I’m at have managed to “get it right” and they, poor normal human shouldn’t be struggling as there is a magic formula or secret sauce that could help. Alas we’re all human and all schools are the same in having struggles, perhaps the only difference being in what they struggle with and how good their marketing and communications departments are in convincing that it is otherwise.

A couple of weeks ago someone asked me about implementing NoodleTools as a citation tool in a school and how to do it. I promised a blog article as I said it wasn’t a simple thing. Ironically just yesterday I had to sincerely offer my apologies to a colleague as I had put zeal in front of our relationship around just that topic. So this is as much a “how to” as a “proceed with caution.

In the information literacy landscape, citations are a sub-topic of academic integrity. Any student who has passed through my hands in the last in the last 10 years will tell you I use the “brushing teeth” analogy with citations. As in – “you don’t just brush your teeth before you go to the dentist” you need to brush them regularly / daily. And I tell them about when I was grading Masters’ students at university how many had an absolute crisis just before submission as they didn’t have a works cited list. Heck I’ve known adult PhD students in a similar situation (and even out of perhaps misplaced righteousness refused to be paid to do it for them). It’s a nice analogy – especially when you add the idea of decayed teeth! It’s also a nice analogy because citations are what Herzberg (1959) would refer to as “hygiene factors” – ie. related to ‘the need to avoid unpleasantness’.

Now to take this a step further – parents and caregivers generally start helping very young children brush their teeth before they even have teeth, with special rubber gadgets they put on their fingers, and it’s even suggested to start early visits to the dentist to acclimatise kids to the idea of having dental checkups. Bear with me. Citations are not just a sub-topic of academic integrity, they’re part of the threshold concept in information literacy of “scholarly discourse”. Now in many areas of life, we learn how to “do” before we learn or understand “why” we do. When my kids were in Chinese Bilingual school aged 6-8 years, they learnt the San Zi Jing (三字經) and some of the three hundred Tang dynasty poems by heart without any comprehension of what they really meant – occasionally to my horror when I saw the translations of filial and patriarchal piety. Not being the kind of person or parent who ever takes things for granted I spent a lot of time trying to understand the mechanisms and reasons for this “learning by heart” and the best I could conclude was just like the English “Grammar” stage of the “Trivium” the ideas is that memorisation is best done at an early age so that logic and rhetoric (analysis and synthesis) can happen later.

So to bring this back to citations – the idea is to initially use a citation tool with pre-selected types and qualities of resources, and the students learn the steps of citing correctly and at a certain point this is expanded to understand what how these resources were selected, what scholarly discourse means along with the other threshold concepts.

Our school has chosen NoodleTools as the citation tool – you can see a set of slides I made on “5 reasons why to use it) including the ability to create inboxes for teachers to follow the process and it’s pedagogical merits of guiding students to make sure they have all the bits and pieces of a good citation. Now do all teachers and students love using it. No. Definitely not. There are a lot of things in education that are absolutely no fun initially but still somehow need to occur. The “hygiene” stuff I’d posit we want to create friction around initially so that they avoid the “unpleasantness” later. Under that heading I’d place things like times-tables, handwriting, spelling, vocabulary, learning facts etc. Now a funny thing about these things is that students will always grumble and grouse about them, but when they master the skills they are so disproportionally happy and proud of it. I notice that in the corridor talk. When in G6 they first encounter citations and NoodleTools they’re all jokey and will call me “Ms NoodleTools” in the hallway. After a couple of times, if teachers consistently use it in their research projects and I’m in the lessons refining and reminding – or rather getting them to do that – they’ll stop me – particularly the boys – and say “Ms, I did it, right? I could tell everyone in the class how to put a book/video/ website into NoodleTools!”

Why is NoodleTools suboptimal so much for so many people? Well, it’s what I’d call an MS-DOS tool. The UX (user experience) is just not what our typical Generation Alpha students or Millennial teachers are used to (or deserve). 12 point font and having to find the right box to click and bits hidden behind drop down menus are not the rizz. PalmPilot back in the 90’s already knew that users didn’t want to have to click several times in order to get to where they wanted to go.

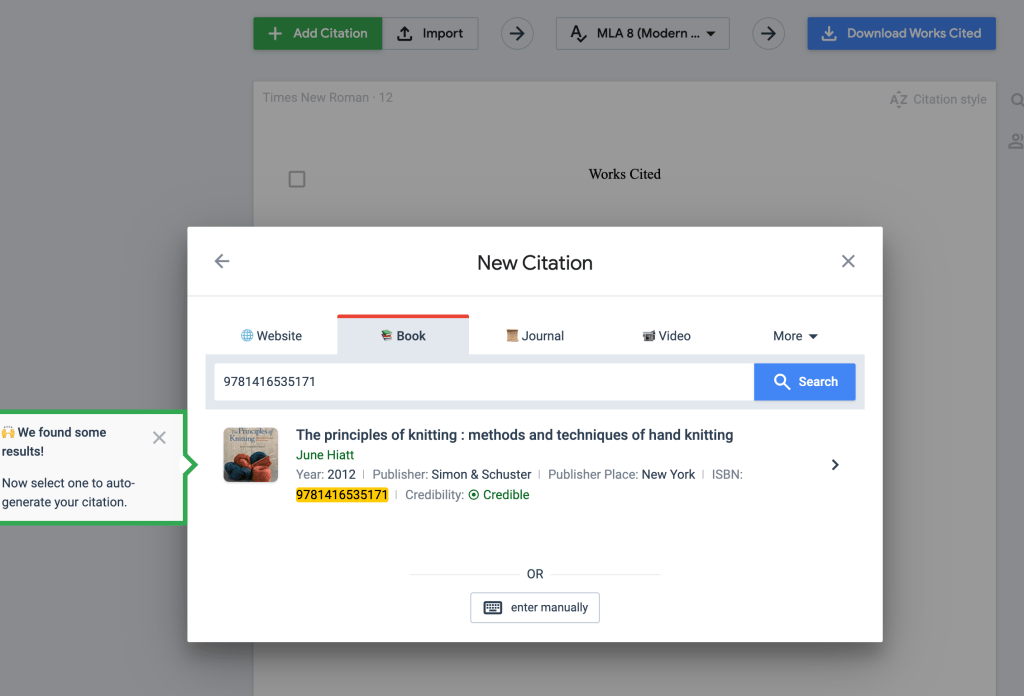

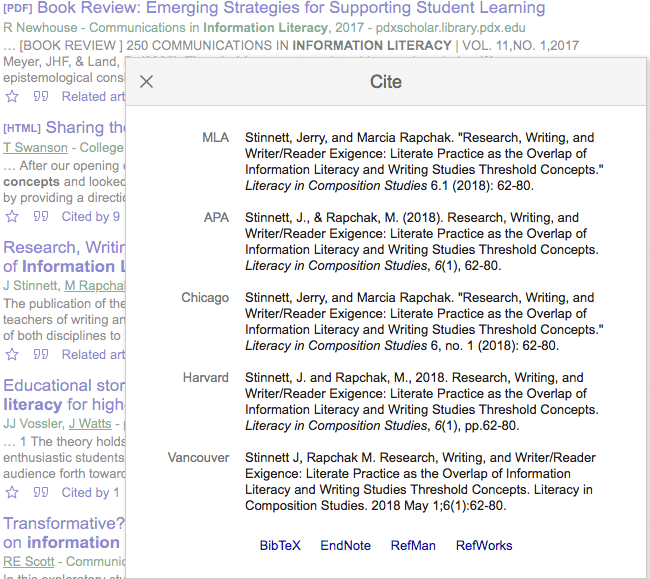

Compare MyBib.com interface and adding a book below – two steps, both visible:

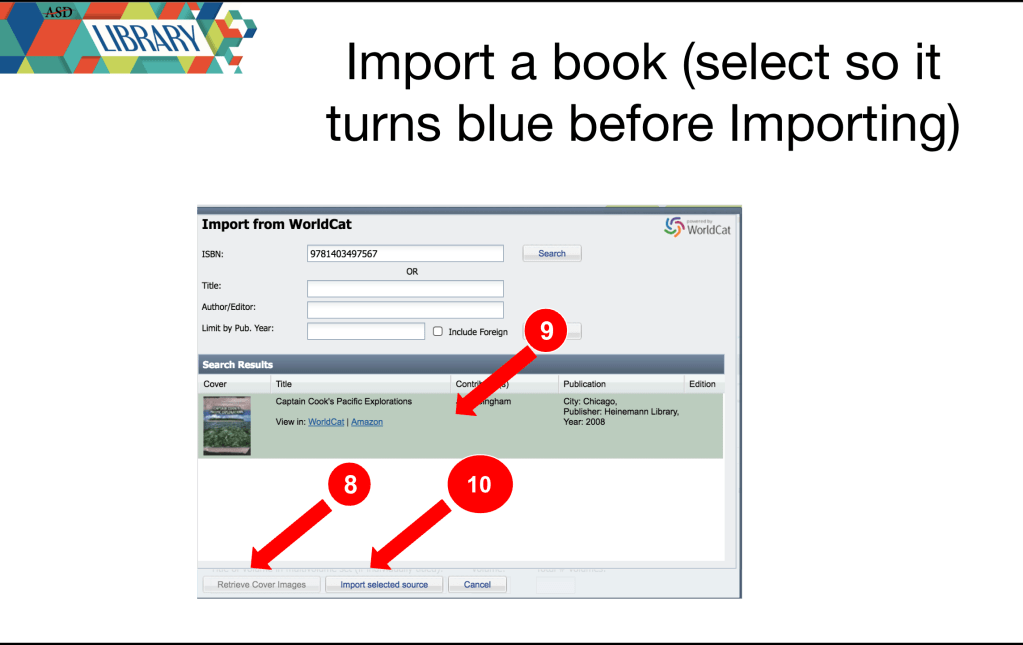

to NoodleTools – twelve steps in 7 consecutive screens (is it any wonder my kids are so proud of remembering it all and getting it right!) – see more here:

Of course there are a myriad of other citation tools, but these are the two more common ones in the secondary school landscape that are not predatory / try to sell you an essay along with your citations or steal your data / information?

So why not go for my.bib – and rather choose Noodletools IMHO? Well:

- it’s not great with identify the Author and Date of sources – all these tools scrape the metadata from the sites you’re using and lazy webmasters and programmers won’t necessarily bother putting these in, or won’t identify them correctly with the correct tags.

- It doesn’t play nice with databases, you need to export the citation in RIS or BibTex format and import it into your MyBib bibliography – where as NoodleTools have managed to integrate themselves into most of the common databases we use, including Credo, Gale, Infobase, JSTOR etc.

- It doesn’t have the same level of pedagogical step-by-step guidance and error identification (for example capitalisation which is very easy to get wrong)

- Teachers can’t follow the research process through a shared “inbox” (and the great thing is in trans-disciplinary assignments the same project can be shared with two different teachers with different class groupings.

- It doesn’t have a notecard / outline function

- It doesn’t have the collaborative features of NoodleTools where you can also see exactly which student contributed which citations / notecards to a project – a great feature when it comes to the “not fair” arguments on work division

- It doesn’t have the “history” feature which allows teachers to see the unfolding of the research and the instances of “immaculate conception” of perfect research papers and notecards

- Although my.bib is free, NoodleTools is only a couple of hundred dollars for nearly 1,000 students i.e incredibly cheap for the extra features

- You actually WANT to create friction in the research process – a source needs to be relevant and credible to merit inclusion in the research and if there are speed-bumps in putting the source in students may be less inclined to go down the WWW (world wild web) route of random googling and more inclined to use our databases and sources in our Libguides.

So how to implement / “sell” the system

Basically it’s a push-me pull-you gig. It helps to have it as part of your information literacy scope and sequence as “the only tool recognised”. If we are student centred it is important that adults set aside some of their preferences and independence so that one system is used and students can become competent and not be confused.

Some of it is persuading departments to adopt it for the above-mentioned reasons, despite it’s ugly UX and multi-step process. Offering to set up inboxes for teachers for research projects helps. As does creating project templates with outlines and tailored notecard headings.

Students need to be taught step by step how to use the tool, and it has to be re-iterated for each assignment and the librarian needs to be prepared to be on hand to help out as there is a very long tail of students becoming competent in its use. And simultaneous to the “doing” skill, the work in the “understanding” has to begin. Why does it matter if something has n.d (no date) or n.a (no author)? How does that correlate to credibility and reliability?

So there was the very long answer to what may have seemed like a simple question. It’s great for Grade 5 to Grade 12. And what do I use personally? Well, if I’m doing an academic paper or helping an adult (or Extended Essay student) sort out their research life I still go for Zotero. I pay for the extra storage even now I’m not a student anymore and I love the integration of in-text citations and Bibliography/Works Cited in Word and GoogleDocs.

In my current position I’m considered to be part of the school wide coaching team, and as a group it was suggested we read “

In my current position I’m considered to be part of the school wide coaching team, and as a group it was suggested we read “ information structure

information structure