Category: CSU

INF530: Blog post 2: Digital Information Ecology

In information ecology, an information system is compared to a natural organism or ecological system whereby internal and external knowledge is integrated in a balanced manner, and information objects, services and products are managed using organisational and digital tools, and sense making “cleaning filters” which adapt and change in response to changes in the environment or the constituents (Candela et al., 2007; Steinerová, 2011; Wang, Guo, Yang, Chen, & Zhang, 2015).

Information ecology is a multi-disciplinary emerging field that covers digital libraries, information ecosystems, e-commerce, networked environments and the issues around rapidly developing new technologies. It offers a framework within which to analyse the relationships between organisations, information technology and information objects in a context whereby the human, information technology and social information environment is in harmony (Candela et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2015). It provides an alternative point of view to the traditional systems design and engineering perspective of information flow, and answers the central question of how to apply knowledge into a dynamic complex organisation.

Nardi and O’Day (1999) explain the interrelationship between people, tools, and practises (cited in Perrault, 2007; Wang et al., 2015) within the context of a shared environment (eco-system) with a cognitive, language, social and value system. The inter-relationship or dependency between the constituents means that changes impact the whole system. Steinerová (2011) and (Candela et al., 2007) looked at the elements of digital libraries and suggested that librarians examine where value integration can take place between the library service, technology, scholarship and culture adding value through new services or contributions to learning, user experience, research productivity, teaching or presenting and preserving cultural heritage.

Applying these ideas to the school environment, constituents of the eco-system include teachers, teacher librarians, students administration, parents and custodial staff (Perrault, 2007). Elements of the system will co-exist but also compete and share, converge and diverge in a dynamic interactive, complex environment (García‐Marco, 2011). The role of the library is such that the information ecology needs to be understood in order to support information seeking behaviour and thereby discover the zones of intervention and areas to leverage to optimise advance information seeking, usage, creation and dissemination within that eco-system and beyond. In response curriculum, content and subject delivery that can be reshaped and constructed dynamically and in a collaborative way according to changes in the environment or needs of students (O’Connell, 2014).

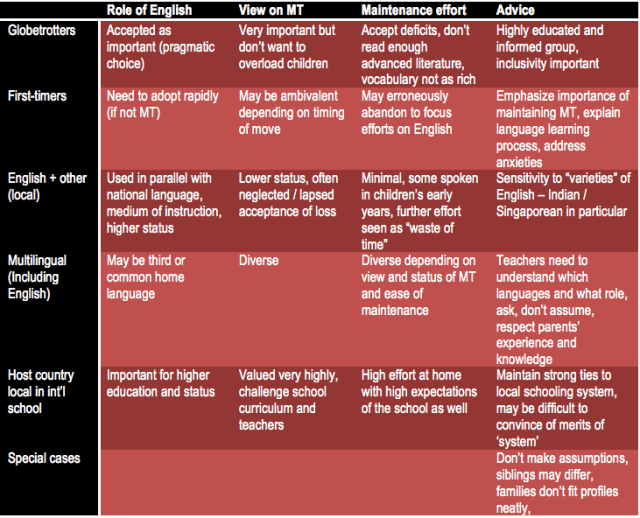

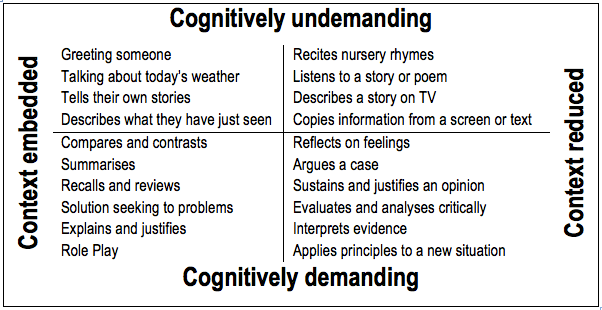

Relating this to my current work, I found the work of Perrault relevant in looking at how multimodal resources and adaptive technologies can best serve students with special educational needs (Perrault, 2010, 2011; Perrault & Levesque, 2012). This type of thinking can be adapted to considering the needs of bi- and multi-lingual students who are part of the school’s information ecology, but have a linguistic and cultural learning and informational need which can be seen as a potential zone of intervention for collaboration between the teacher, teacher librarian, family and community. Provided of course that within the international school group dynamic and context it is understood what is specific to particular linguistic and cultural groups and what is generalizable (Vasiliou, Ioannou, & Zaphiris, 2014) and how best to integrate systematic change and innovation, cognizant of the consequences that may be direct, indirect, desirable and undesirable, and often unanticipated despite our best efforts (Perrault, 2007).

References:

Candela, L., Castelli, D., Pagano, P., Thanos, C., Ioannidis, Y., Koutrika, G., … Schuldt, H. (2007). Setting the Foundations of Digital Libraries – The DELOS Manifesto. D-Lib Magazine, 13(3/4).

García‐Marco, F. (2011). Libraries in the digital ecology: reflections and trends. The Electronic Library, 29(1), 105–120. http://doi.org/10.1108/02640471111111460

O’Connell, J. (2014, July 19). Information ecology at the heart of knowledge [Web Log]. Retrieved March 28, 2015, from http://judyoconnell.com/2014/07/19/information-ecology-at-the-heart-of-knowledge/

Perrault, A. M. (2007). The School as an Information Ecology: A Framework for Studying Changes in Information Use. School Libraries Worldwide, 13(2), 49–62. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=28746579&site=ehost-live

Perrault, A. M. (2010). Reaching All Learners: Understanding and Leveraging Points of Intersection for School Librarians and Special Education Teachers. School Library Media Research, 13, 1–10. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=67740987&site=ehost-live

Perrault, A. M. (2011). Rethinking School Libraries: Beyond Access to Empowerment. Knowledge Quest, 39(3), 6–7. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=58621336&site=ehost-live

Perrault, A. M., & Levesque, A. M. (2012). Caring for all students. Knowledge Quest, 40(5), 16–17. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=82564002&site=ehost-live

Steinerová, J. (2011). Slovak Republic: Information Ecology of Digital Libraries. Uncommon Culture, 2(1), 150–157. Retrieved from http://pear.accc.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/UC/article/view/4081

Vasiliou, C., Ioannou, A., & Zaphiris, P. (2014). Understanding collaborative learning activities in an information ecology: A distributed cognition account. Computers in Human Behavior, 41(0), 544–553. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.057

Wang, X., Guo, Y., Yang, M., Chen, Y., & Zhang, W. (2015). Information ecology research: past, present, and future. Information Technology and Management, 1–13. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-015-0219-3

Blog Task 1: INF530

At the risk of being facetious I’d like to compare my current state of knowledge to the old jaw about being “as old as your tongue and a little older than your teeth”. It is so hard to define where one is in terms of knowledge and understanding in just about any field, particularly this one. Throughout my journey in the MIS (Master of Information Studies) I’ve attempted to grasp at every opportunity to not only be exposed to the digital concepts and practices of information studies and education, but also to integrate them into my own professional, educational and private life. Yet I don’t know what I don’t know. I’ve written before about the anosognosic’s dilemma, and each course refer back to the excellent article by Morris (2010).

The context of my learning professionally is working part-time as an “apprentice” in the secondary library of a K-12 international school in Singapore while I complete my Masters in Education. My “master” is well entrenched in the digital world and steps bravely where many shy away. We spoke recently about the teachers who employ the old tactics of the formerly illiterate, the phrases “I’ve forgotten my glasses, / it’s too dark / too small can you just read that for me?” have been replaced by “I don’t have time / you’re so much quicker at doing that / do you mind quickly finding …” or more defensive negations of the entire digital realm.

A school has a number of constituencies; one that I like to try and focus time and energy on as a librarian are the parents. I’ve also spent quite a few years discovering where the intersection of my interests, passions and profession lies. As a person who grew up bilingual and has spent the last 23 years living in different places around the world, each time learning new languages, the idea of language, mother tongue maintenance and sustainability preoccupies me. I also believe it is an area where we (as teacher librarians) can make a significant difference by leveraging our knowledge of personal learning networks / environments and communities of practice even if we are not bi or multi-lingual ourselves. I recently held a parents’ forum at school with our self-taught language coordinator that was very well received. I have fallen into this area by dint of interest and co-incidence, however with the benefit of hindsight I make some guesses at why this would be a good area to commence evangelizing about the benefits of digital learning. There is a need / deficit in the current models, specialization is globally dispersed, and the current practices and lack of emphasis make it a low stakes area for experimentation. Given global mobility through choice or circumstance it is also an area that will need considerable attention in the future.

In my opinion the central theme in all these discussions is that of ownership and control. And the battling for or relinquishing of control and ownership over learning is at the heart of conflicts over curriculum, teaching and learning philosophy – how threatening guided inquiry, collaboration and formative assessment can be! Following through on the concepts, practice and promise of what we are learning may prove to be very unsettling for the status quo and vested interests. Which side are we on personally in our own learning and professionally as gatekeepers or conduits of the learning of others?

Morris, E. (2010, June 20). The Anosognosic’s Dilemma: Something’s Wrong but You’ll Never Know What It Is (Part 1). Retrieved February 4, 2014, from http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/the-anosognosics-dilemma-1/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=1

New Course

This time it is INF530 – Concepts and Practices for a Digital Age.

Even my blog(s) header(s) have been updated with a pretty picture I took in Myanmar.

Yup, we’re moving house AGAIN. I’ve stopped even counting local moves and just count the trans-continental ones these days. It was the usual landlord games of wanting to hike up the rent in a falling market – between the landlord trying to increase the rent (no go, I just found a place at the same price – which was 30% cheaper than the advertised price), the school increasing school fees, and CSU increasing the university fees (46% from my MIS if you please …) without any salary increase and bonus freezes, it’s going to be a tight year. But that leaves me with having to pack up, sort out and declutter before mid March – oh, and did I mention my inlaws arrive just after the move? Luckily my MIL is an ace at helping me get sorted.

But decluttering is good. And necessary. And even after 2 years we’ve accumulated stuff that can go. So that’s what I’ll be doing in between getting my study life sorted.

Digital Storytelling tools worth looking at (1)

Here are a few of the tools I’ve experimented with personally, or have seen well used during my INF533 Literature in Digital Environments course at CSU (if you’re looking for a great course to upskill yourself, I can thoroughly recommend it – you can take it as a single course “just for fun” and it is fun).

Creativist is an example of “scrollitelling”. It’s a really low-barrier tool where you can combine pictures and video with a story. The free version limits the size of your files (150 MB). DW Academie gives a rather nice guide here which is worth reading through before you try.

|

| https://www.creatavist.com/featured |

Inklewriter by Inklestudios is a platform for interactive choice based stories. It is really easy to get started on and in its simplest version one can just add text. Photos can be added relatively easily but there is no video option, which is a pity. I can see great possibilities for use with students who are exploring options for example of subject choice or university or study choices – they could explore options and alternatives in a “safe” and personal environment imagining “what if…”

|

| http://www.inklestudios.com/firstdraft/ |

Popcorn Webmaker by Mozilla is another easy “plug and play” tool. It uses some of the basic conventions of video editing with various layers (sound, video, picture) and allows one to embed elements in a story. One of the interesting variations on this is that the interactive element allows the audience to remix the original and make their own stories.

|

| https://urbanstorytellers.makes.org/thimble/MzY3OTE5MTA0/urban-storytelling-a-how-to-guide-start-here |

- Kathy Shrok

- Joyce Valenza

- Submarine Channel

- Mindshift

- 50 ways

- 9 Tools for Journalists (some very good tools)

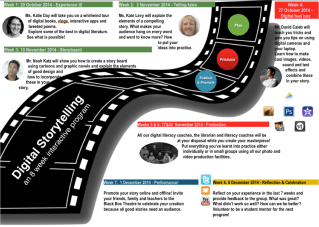

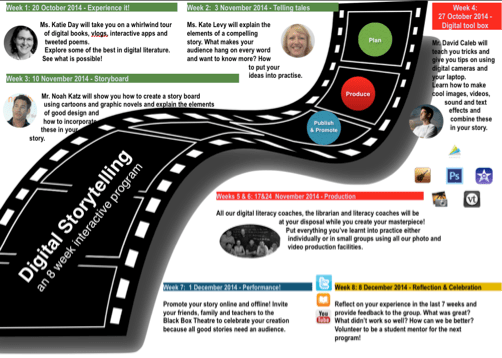

Digital Storytelling – an 8-week interactive program for Middle School students

____________________________________________________________________

Assessment Item 1: Report and program for specified age group

INF 505 – Library Services for Children and Youth

___________________________________________________________________

Part 1: Background and context

|

Section

|

Number

|

|

Kindergarten

|

353

|

|

Primary School

|

654

|

|

Middle School

|

587

|

|

High School

|

324

|

|

IB

|

321

|

|

Total

|

2,239

|

Part 2: Design and develop a program

Goals and objectives

|

Objective

|

Relevance

|

Related Developmental need

|

|

1. Introduce students to concepts, examples and tools of digital storytelling

|

Students are familiar with literature and with digital tools, however not with digital storytelling. This will broaden their competencies while scaffolding on what they already know.

|

Competence and achievement

Structure and clear limits |

|

2. Support students in the creation of their own narratives using the tools of digital storytelling

|

For successful creative output, students will need technical, literacy and social support in an encouraging non-judgmental environment

|

Creative expression

Positive social interaction with Adults and Peers Competence and Achievement Opportunities for Self-definition |

|

3. Provide a forum for sharing, promotion, collaboration and interaction

|

Student’s digital storytelling outputs receive validation through providing an appreciative audience while allowing them to contribute the same to their fellow participants.

|

Positive social interaction with Adults and peers

Meaningful participation |

Figure 2: Objectives, relevance and developmental needs

Cost, staffing and other logistical considerations

Program delivery

Week 1: Experience it!

Week 2: Telling Tales

Week 3: Storyboard

Week 4: Digital tool box

Weeks 5 & 6: Production

Week 7: Performance

Week 8: Reflection and celebration

Detailed activity plan – Week 1

Materials required

|

Type

|

Name

|

Link

|

|

Interactive Documentary

|

A global guide to the first world war (Panetta, 2014)

|

|

|

Twitterature

|

100 Greek Myths retold in 100 tweets (Crown Publishing, 2012)

|

|

|

Digital Novel

|

Inanimate Alice (DreamingMethods, 2012)

|

|

|

Vlog

|

Lizzie Bennet Diaries (Su, Noble, Rorick, & Austen, 2014)

|

|

|

Animated dreamtime stories

|

Dust Echoes (ABC, 2007)

|

|

|

iPad app and eBook

|

Shakespeare in Bits – Romeo and Juliette (Mindconnex Learning Ltd, 2012)

|

Figure 4: Digital Literature examples for screening

Step by step procedures of what is to be done

|

Item

|

Equipment / Material

|

Timing

|

|

Greet students and ask for a brief introduction with name, class, where they are from and any experience or expectations they have from the program.

|

Stickers for students to write the names on

|

10 minutes

|

|

Perform a short icebreaker such as “two truths and one lie” with students in pairs.

|

n/a

|

10 minutes

|

|

Ask students to do initial survey using google forms.

|

Survey (Appendix 3)

|

5 minutes

|

|

Show snippets of the first three examples of digital story telling – A Global guide to the first world war, 100 Greek Myths and Inanimate Alice.

|

Laptop, projector and screen. Ensure various resources are open to minimise turnover time

|

3 resources, 5 minutes each = 15 minutes

|

|

Open discussion on what appeals to the students

|

Use the elements of successful digital story telling i.e. Interactive; Authentic; Meaningful; Technological; Organized; Productive; Collaborative; Appealing; Motivating; and Personalized (Yoon, 2013) to scaffold activity

|

20 minutes

|

|

Give students a break to have a snack, use the washroom, etc.

|

10 minutes

|

|

|

Show snippets of the next three examples of digital story telling – Lizzie Bennet Diaries, Dust Echoes and Shakespeare in Bits – Romeo and Juliette.

|

Laptop, projector and screen. Ensure various resources are open to minimise turnover time.

|

3 resources, 5 minutes each = 15 minutes

|

|

Ask students to choose the type of digital storytelling that most appeals to them; they can explore the resource in the remaining class time and borrow the resource to explore further at home.

|

Assist with loan and downloading of materials or searching of similar materials.

|

20 minutes

|

|

Finish in time for buses / pickup

|

Total 1 hour 45 minutes

|

Figure 5: Step by Step Procedure for week 1

Audience, staffing and other considerations

Marketing and promotion

Part 3: Evaluation and reflection

How to evaluate the program

Reflection

|

Objective

|

|

1. Introduce students to concepts, examples and tools of digital storytelling

|

|

2. Support students in the creation of their own narratives using the tools of digital storytelling

|

|

3. Provide a forum for sharing, promotion, collaboration and interaction

|

Figure 7: Objectives revisited

|

Developmental Need

|

Expression

|

Program Objectives

|

Program characteristics

|

|

Positive Social Interaction with Adults & Peers

|

Seek attention, socialization

|

2, 3

|

Small group of students with specialist teachers with a variety of skills and personalities

|

|

Structure & Clear Limits

|

Push boundaries, challenge authority

|

1, 2, 3

|

Program is limited to 8 sessions with a clear structure within which choice and autonomy is possible

|

|

Physical Activity

|

Running, jostling, roaming

|

n/a

|

Not applicable

|

|

Creative Expression

|

Vandalism, Vine, Instagram, Snapchat

|

2

|

Creative storytelling is the main thrust of the program

|

|

Competence & Achievement

|

Competitive behaviour, Minecraft, number of followers on social media

|

1,2,3

|

The program allows for mastery of technological and storytelling skills within a new format, end result is performed and published

|

|

Meaningful Participation

|

Opinionated, socialization, clique club or team membership

|

2, 3

|

Activities allow for interaction in the physical and virtual space

|

|

Opportunities for Self-Definition

|

Status symbols, dress and hair,

|

2

|

Students are encouraged to consider their culture, linguistic and social identities in producing their story

|

Figure 8: Summary of developmental needs, expression, program objectives and characteristics

References

ABC. (2007). Dust Echoes. Retrieved August 20, 2014, from http://www.abc.net.au/dustechoes/dustEchoesFlash.htm

Barnard, C., A. (2011). How Can Teachers Implement Multiple Modalities into the Classroom to Assist Struggling Male Readers? (Education Masters Paper 26). St. John Fisher College, Rochester, NY.

Beach, R. (2012). Uses of Digital Tools and Literacies in the English Language Arts Classroom. Research in the Schools, 19(1), 45–59.

Buchholz, B. (2014). “Actually, that’s not really how I imagined it”: Children’s divergent dispositions, identities, and practices in digital production. In Working Papers in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education (Vol. 3, pp. 25–53). Bloomington, IN: School of Education, Indiana University. Retrieved from http://education.indiana.edu/graduate/programs/literacy-culture-language/specialty/wplcle/index.html

Burke, Q., & Kafai, Y. B. (2012). The writers’ workshop for youth programmers: digital storytelling with scratch in middle school classrooms (pp. 433–438). Presented at the Proceedings of the 43rd ACM technical symposium on Computer Science Education, ACM.

Crown Publishing. (2012, November). @LucyCoats: 100 Greek Myths Retold in 100 Tweets (with tweets). Retrieved September 4, 2014, from https://storify.com/CrownPublishing/100-greek-myths-retold-in-100-tweets

DreamingMethods. (2012). Inanimate Alice – About the Project [Digital Novel]. Retrieved September 4, 2014, from http://www.inanimatealice.com/about.html

Dreon, O., Kerper, R. M., & Landis, J. (2011). Digital Storytelling: A Tool for Teaching and Learning in the YouTube Generation. Middle School Journal, 42(5), 4–9.

Gallaway, B. (2008). Pain in the Brain: Teen Library (mis)Behavior. Retrieved September 4, 2014, from http://www.slideshare.net/informationgoddess29/pain-in-the-brain-teen-library-misbehavior-presentation

Gorrindo, T., Fishel, A., & Beresin, E. (2012). Understanding Technology Use Throughout Development: What Erik Erikson Would Say About Toddler Tweets and Facebook Friends. Focus, X(3), 282–292. Retrieved from http://focus.psychiatryonline.org/data/Journals/FOCUS/24947/282.pdf

Green, M. R. (2011). Writing in the Digital Environment: Pre-service Teachers’ Perceptions of the Value of Digital Storytelling. In American Educational Research Association (pp. 8–12). Retrieved from http://worldroom.tamu.edu/Workshops/Storytelling13/Articles/Green.pdf

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., & Hughes, J. E. (2009). Learning, Teaching, and Scholarship in a Digital Age: Web 2.0 and Classroom Research: What Path Should We Take Now? Educational Researcher, 38(4), 246–259. doi:10.3102/0013189X09336671

Gunter, G. A., & Kenny, R. F. (2008). Digital booktalk: Digital media for reluctant readers. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 8(1), 84–99.

Gunter, G. A., & Kenny, R. F. (2012). UB the director: Utilizing digital book trailers to engage gifted and twice-exceptional students in reading. Gifted Education International, 28(2), 146–160. doi:10.1177/0261429412440378

Hall, M., Hall, L., Hodgson, J., Hume, C., & Humphries, L. (2012). Scaffolding the Story Creation Process. In 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education. Porto, Portugal. Retrieved from http://www.lynnehall.co.uk/pubs/ScaffoldingTheStoryCreationProcess.pdf

Jones, P., & Waddle, L. L. (2002). New directions for library service to young adults. Chicago: American Library Association.

Kenny, R. F. (2011). Beyond the Gutenberg Parenthesis: Exploring New Paradigms in Media and Learning. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 3(1), 32–46. Retrieved from http://www.jmle.org

Kenny, R. F., & Gunter, G. A. (2004). Digital booktalk: Pairing books with potential readers. Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 27, 330–338.

Knight, S. (2012, June 20). Introduction to Digital Storytelling. Retrieved September 6, 2014, from http://www.slideshare.net/sknight/digital-storytelling-ed554?related=1

Meyers, E. M., Fisher, K. E., & Marcoux, E. (2007). Studying the everyday information behavior of tweens: Notes from the field. Library & Information Science Research, 29(3), 310–331. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2007.04.011

Mindconnex Learning Ltd. (2012, January 25). Shakespeare In Bits: Romeo & Juliet iPad Edition on the App Store [iTunes]. Retrieved September 6, 2014, from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/shakespeare-in-bits-romeo/id370803660?mt=8

Morgan, H. (2014). Using digital story projects to help students improve in reading and writing. Reading Improvement, 51(1), 20–26. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1540737338?accountid=10344

Musil, R. (2001). The confusions of young Törless. (S. Whiteside, Trans.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books.

Nilsson, M. (2010). Developing Voice in Digital Storytelling Through Creativity, Narrative and Multimodality. International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 6(2), 148–160. Retrieved from http://seminar.net/index.php/volume-6-issue-2-2010/154-developing-voice-in-digital-storytelling-through-creativity-narrative-and-multimodality

Panetta, F. (2014). A global guide to the First World War [Interactive documentary]. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2014/jul/23/a-global-guide-to-the-first-world-war-interactive-documentary

Ragen, M. (2012). Inspired technology, inspired readers: How book trailers foster a passion for reading. Access, 26(1), 8–13. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/934354989?accountid=10344

Reynolds, G. (2008). Chapter 6 Presentation Design: Principles and Techniques. In Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery (pp. 152–163). New Riders. Retrieved from http://www.presentationzen.com/chapter6_spread.pdf

Su, B., Noble, K., Rorick, K., & Austen, J. (2014). The secret diary of Lizzie Bennet. London ; Sydney: Simon & Schuster.

Thompson, I. (2012). Stimulating reluctant writers: a Vygotskian approach to teaching writing in secondary schools: Stimulating reluctant writers. English in Education, 46(1), 85–100. doi:10.1111/j.1754-8845.2011.01117.x

UWCSEA. (n.d.). Languages at UWCSEA. Retrieved from http://issuu.com/uwcsea/docs/uwcsea_languages

Yoon, T. (2013). Are you digitized? Ways to provide motivation for ELLs using digital storytelling. International Journal of Research Studies in Educational Technology, 2(1). doi:10.5861/ijrset.2012.204

Appendix 1: Program Overview

|

Element

|

Synopsis

|

Relevance

|

Instructor

|

Location

|

|

|

Week 1:

20 October 2014

|

Experience it!

|

A whirlwind tour of digital books, vlogs, interactive apps and tweeted poems.

|

Provide background to program and give understanding of what is possible.

|

Ms. Katie Day – secondary school librarian – expert in YA literature

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 2:

27 October 2014

|

Telling tales

|

Elements of storytelling explained with particular reference to digital storytelling.

|

Storytelling, no matter what the medium is the basis of this program.

|

Ms. Kate Levy – high school English teacher

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 3:

3 November 2014

|

Storyboard

|

Students shown how to create a storyboard using the example of cartoons and graphic novels and elements of good design are introduced.

|

Learn the elements of good design and how to incorporate these in your story.

|

Mr. Noah Katz – visual literacy coach

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 4:

10 November 2014

|

Digital tool box

|

Digital tools for capturing and combining different modal choices (image, sound, text) are explained. Best practise is highlighted.

|

Bring students digital skills to a comparative level of mastery and show how to incorporate into their storytelling.

|

Mr. David Caleb – digital literacy coach, photographer and author of “The Photographer’s Toolkit”

|

Library Think Tank

|

|

Week 5:

17 November 2014

|

Production

|

Students will be given the time and resources to put their ideas and skills into practise. They can choose between individual, paired or group production.

|

Students will be aided in their creation of digital stories by competent experts they can achieve their creative goals within a clear structure.

|

All 7 school digital literacy coaches, librarian and Ms. Levy

|

Library – Emily Dickinson, Pablo Neruda rooms & Think Tank – green, blue or white screens available

|

|

Week 6:

24 November 2014

|

Production

|

||||

|

Week 7:

1 December 2014

|

Performance!

|

Output is produced and promoted. Friends, family and teachers are invited to the Black Box Theatre watch the digital storytelling productions.

|

An explicit audience is an important aspect of storytelling. Students will have a sense of competency and achievement.

|

Ms. Katie Day, participants, digital literacy coaches

|

Black Box Theatre

|

|

Week 8:

8 December 2014

|

Reflection

|

Time is given for reflection and feedback of the last 7 weeks. The end results are celebrated and promoted further.

|

The end of the program is indicated by this activity both setting a limit to the formal program and allowing reflection and also validating participants by requesting their evaluation and suggestions for improvement.

|

All instructors

|

Library Think Tank

|

Appendix 2: Promotional Calendar

Appendix 3: Pre-program Survey

|

Definitely

|

Usually

|

Some-what

|

Not really

|

Not at all

|

|

|

I enjoy reading or watching

|

|||||

|

Fiction, stories, memoirs

|

|||||

|

Non-fiction or documentaries

|

|||||

|

Poetry

|

|||||

|

I can use the following technology

|

|||||

|

Digital Camera

|

|||||

|

Digital Video Camera

|

|||||

|

iPhoto

|

|||||

|

Photoshop

|

|||||

|

iTunes

|

|||||

|

Garage Band

|

|||||

|

iMovie

|

|||||

|

I use the following social media

|

|||||

|

Facebook

|

|||||

|

Instagram

|

|||||

|

Twitter

|

|||||

|

YouTube

|

|||||

|

Other – please state which ……

|

|||||

|

I express my creativity through

|

|||||

|

Writing

|

|||||

|

Art or photography

|

|||||

|

Music or dance

|

|||||

|

Drama and acting

|

|||||

|

Video or film

|

|||||

|

I am not creative

|

|||||

|

What do you expect from this program?

|

|||||

Appendix 4: Post Program Survey

|

Definitely

|

Usually

|

Some-what

|

Not really

|

Not at all

|

|

|

I understand the concepts and tools of Digital Storytelling

|

|||||

|

Different types of digital stories

|

|||||

|

What is important in storytelling

|

|||||

|

How to create a storyboard

|

|||||

|

I can produce my own digital story

|

|||||

|

I can use the following technology

|

|||||

|

Digital Camera

|

|||||

|

Digital Video Camera

|

|||||

|

iPhoto

|

|||||

|

Photoshop

|

|||||

|

iTunes

|

|||||

|

Garage Band

|

|||||

|

iMovie

|

|||||

|

I would recommend this program

|

|||||

|

To friends / classmates

|

|||||

|

To teachers

|

|||||

|

What was the best / most positive part of this program?

|

|||||

|

What didn’t you enjoy about this program?

|

|||||

|

What improvements would you suggest?

|

|||||

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Research summary on Language

_________________________________________________________________________________

Background Research

This study has presented the typical knowledge management dilemma – there is a considerable amount of information and research, both academic and practical but it is widely dispersed and personal experience is often not documented.

History

Most research into BML (bi- and multi-lingualism) concerns itself with assimilation of immigrants (Fillmore, 2000; Slavin, Madden, Calderon, Chamberlain, & Hennessy, 2011; Slavin et al., 2011; Winter, 1999); maintaining minority (or majority) languages in a dominant language environment (Ball, 2011; Dixon, Zhao, Quiroz, & Shin, 2012) or language immersion or bilingual programmes; (Caldas & Caron-Caldas, 2002; Carder, 2008; Cummins, 1998; Genesee, 2014; Hadi-Tabassum, 2004; Soderman, 2010) aspects of which may or may not be relevant to this study or its population.

Bilingualism

Researchers distinguish between three types of bilingualism. Simultaneous bilingualism – exposure to two languages from birth; early successive bilingualism – first exposure aged 1 – 3 years; and second language bilingualism – first exposure aged 4 – 10 years. There is considerable debate as to what exactly the “critical” ages are for successful language learning. As Kirsten Winter pointed out “Language learning is a continuum and bilingualism is not a perfect status to be achieved.” (Winter, 1999, p. 88). Typical language learners cycle through alternating stages of passive (receptive) and productive (expressive) skills, usually in the order of listening, speaking, reading and then writing.

Factors Impacting Acquisition

Researchers agree on a number of factors which impact on the successful acquisition and retention of a second or subsequent language in the BML population. These relate to the student, family, school and the community or society.

Student

Family

A large vocabulary in any language contributes to overall “oral proficiency, word reading ability, reading comprehension, and school achievement”(Dixon, Zhao, Quiroz, et al., 2012, p. 542). Vocabulary is influenced by the parent’s level of education, access to and availability of resources, and the quality and quantity of parent-child interactions, including shared reading, frequency of story telling and conversations.

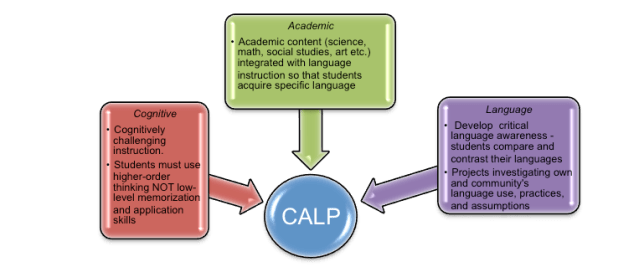

School

The International school context results in a number of issues that complicate MT provision, including the multicultural and multilingual nature of the student population, resulting in ‘fictive monolingualism’ and the transience of both the student and teacher population, with the resultant socio-psychological implications on learning (Caldas & Caron-Caldas, 2002; Hacohen, 2012; Hornberger, 2003). However, where the “cultural capital” of the school included valuing language diversity in its environment and teaching practise, students had an increased sense of belonging, higher levels of reading literacy and they scored significantly higher academically. Continued development of ability in two or more languages on a daily basis resulted in a deeper understanding of language across contexts. Best practice includes a well structured MT program with at least some inclusion in the school timetable and fee structure, inclusion of other subject matter in MT lessons, support for English acquisition through a daily ESL/EAL program, a socio-culturally supportive environment, better awareness and training for subject teachers, affirmation of students’ identity as bi- or multi-lingual and collaboration with parents, while block scheduling was not optimal for language learning (Carder, 2014; IBO, 2011; Tramonte & Willms, 2010; Vienna International School, 2006; Wallinger, 2000). Research in heritage language (HL) teaching and learning indicates that macro-approaches and other specific strategies that build on learners’ existing language skills could be leveraged to improve reading and writing abilities, increase motivation and participation and validate students’ identity although specific teacher training for HL is recommended (Lee-Smith, 2011; Wu & Chang, 2010).

Community and Society

The support of a locally based language community, including faith and cultural communities had a positive impact which could mitigate socio-economic status (SES) factors and enhance learning through beliefs and practises, classes and cultural and religious activities (Dixon, Zhao, Quiroz, et al., 2012). Finally the availability of and access to learning resources, complementary schooling, books and other materials impacted on acquiring and maintaining language(Scheele, Leseman, & Mayo, 2010)

Concerns

Although the value of BML has become more widely accepted and most parents and educators appreciate and encourage the process, a number of concerns have rightly been voiced on the process and efficacy of reaching the goal of a BML child. In the first instance, the quality of the productive language – oral and or written skills – of one or all of the child’s languages may not develop to a sufficiently high level for academic or employment purposes (Cummins, 1998).

References:

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Assessment Item 8: Digital Storytelling Project and Reflection

Part A: Context for Digital Story Telling Project

“Knowledge, then, is experiences and stories, and intelligence is the apt use of experience, and the creation and telling of stories. Memory is memory for stories, and the major processes of memory are the creation, storage, and retrieval of stories.” (Schank & Abelson, 1995, p. 8)

In Asia, particularly Hong Kong, where parenting is a competitive sport, giving your children the opportunity to learn Chinese has become the holy grail of expatriate parenting. Children are enrolled in language programs and immersion schools without much understanding or consideration of the possible consequences. Research is scant, seldom longitudinal and evidence is mainly anecdotal, A focus on positive success stories and oral ability prevails, while a climate of shame and fear prevents openness, analysis and understanding when children do not succeed.

Our family’s story of “chasing the dragon” is one of success, failure and ultimate triumph. Storytelling is a way of making sense of events and experiences and communicating this (Botturi, Bramani, & Corbino, 2012) to others in a similar situation.

The subject area covers language, bilingualism and mother tongue from both a pedagogical and socio-emotional point of view. The purpose is to illuminate the complexities underlying language choices in families in the international school context through storytelling. The intended audience are parents, educators and administrators in International Schools. This story will be basis of a presentation at a conference on language next year. It will be used to add context to academic theory on mother-tongue, language learning and identity so that educators and parents alike not only have an intellectual understanding of the theories but an emotional response through this story to the platitude that “every child is unique”.

Academics and educators may lose sight of the fact that the audience that may best profit from their research and knowledge on bilingualism may only be vaguely aware of the information they need, often filtered through their own or other’s experience (King & Fogle, 2006). The intended audience of this project may have not have the time, inclination or access to scholarship in a form and format that is easily understood and resonates with them. Stories influence “attitudes, fears, hopes, and values” and are more effective at changing belief than persuasive writing as a result of changing how information is processed by the audience (Gottschall, 2012) due to escape into an alternative reality, connection with characters, emotional involvement and self-transformation (Green, Brock, & Kaufman, 2004). The affordances of digital story-telling including audience participation enhance this engagement (Alexander, 2011). Although students are required to have a high level of English proficiency, often parents do not and their learning needs may therefore not be met. The affordance of digital storytelling is to incorporate multi semiotic systems that ‘allow for the linking and integration of cognitive, tacit, affective, cultural, personal, graphic and photographic ways of exploring, articulating, expressing and representing sense-making about learning and identity’ (Williams, 2009, cited in Walker, Jameson, & Ryan, 2010, p. 219).

Within the international school context, language is an area fraught with assumptions, misapprehension and emotion . This interactive digital experience has value for program implementation as it highlights many of the issues surrounding language acquisition and maintenance in an accessible format allowing for both breadth and depth in understanding of the topic. Parents, with the best intentions in the world make pedagogically unsound decisions while educators, often coming from a mono-lingual background, may be unable to assist families in their linguistic paths and school administrators may be hampered to do right by the individual due to the logistical and cost complexity of catering to multiple linguistic backgrounds and nuances.

This project aims to increase awareness in all intended audiences so that choices can be made based on current understanding of best practice, educational and logistical issues and potential hurdles along the way. Perhaps we can let go of the “holy grail” of Chinese at the cost of our mother tongues and embrace, pursue and celebrate our own languages, culture and identity, reassured by what we know about language skill transferability.

Part B: Digital Story Telling Project

URL: chasingthechinesedragon.blogspot.com

Please note:

In the creation of my digital story, I have made extensive use of old video footage and photos of my children and others in a classroom setting. I have received the permission from my children to do so, and they partook in a series of interviews with me. However, in order to preserve their and others privacy and confidentiality I have decided to make the product and the blog in which the content occurs private until they are old enough to give permission that is legally binding. As they are now aged 11 and 12, I do not think their consent is as informed as it should be.

I would therefore request people to email me their email addresses so that I can include them on the list of people with permission to access the blog. I’m sorry for the inconvenience around this.

I have discussed this with a number of educators at our school and they feel this is the best way to proceed.

I will use some of the video clips and research for the presentation at the language conference in May, but that will be a dynamic rather than static presentation which will limit the exposure to a wide audience without the necessary context.

Part C: Critical Reflection

There are a number of dimensions related to working as an educational professional in the increasingly pervasive digital environment. We no longer merely have a duty to teach content and information but need to equip ourselves, and our students with digital literacy and critical evaluative skills to deal with the multi-modal formats encountered in the education journey.

Value of digital story telling

In the “context” section, it was highlighted how effective stories are in changing belief and how information is processed and understood including the emotional engagement and interactive potential of digital media (Bailey, 2014c; Coleborne & Bliss, 2011; Gottschall, 2012; Green et al., 2004; Matthews, 2014). A case can also be made for the role storytelling has in assimilating knowledge and memory (Schank & Abelson, 1995).

Tools and strategies for teaching / learning

In a recent essay, The Economist proposes a hierarchy of knowledge and learning and distinguishes between digital formats that have a function of “presenting people with procedural information they need in order to take on a simple task or fulfil a well-stated goal” versus teaching through “books” that can have its “pedagogy enriched by embedded media and software that adapts them to the user’s pace and needs” (The Economist, 2014, Chapter 5). Certainly the digital realm offers the possibility of engaging learners in a multi-modal environment which is more likely to resonate with their preferred way of receiving information provided the educator has a good understanding of how to select and use the tools (Anstey & Bull, 2012; Bowler, Morris, Cheng, Al-Issa, & Leiberling, 2012; Phillips, 2012; Unsworth, 2008; Walsh, 2010).

As educators our role needs to evolve and combine aspects of discovery, critical evaluation and enabling access to the most appropriate material (Dockter, Haug, & Lewis, 2010; Leacock & Nesbit, 2007; Nokelainen, 2006; Parrott, 2011), while at the same time educating our students to be mindful consumers and producers of content aware of the “weapons” in their and other’s storytelling “arsenal” and how these can be deployed for good and ill (Gottschall, 2012; Walker et al., 2010; Walsh, 2010).

Then there is the psycho/socio-neurological dimension of the impact digital literature has on how our students access, absorb, process and reflect on information and learning (Edwards, 2013; Goodwin, 2013; Jabr, 2013; Margolin, Driscoll, Toland, & Kegler, 2013; Wolf & Stoodley, 2008). Finally, for our students there are questions around the evolution of their skill sets as they move from consumption of digital products to creation, expression, engagement and interactivity (Hall, 2012).

Current and future developments

An exciting function of digital creations is the way materials can meet learning needs of all types of learners (Kingsley, 2007; Rhodes & Milby, 2007). However, one has to wonder about ephemeral nature of material, formats and platforms in the digital environment with the related issues of curation, preservation and archiving. Just as it appears that blogging as a tool for learning and storytelling has had its rise and demise, so too other platforms may not have longevity.

The whole field appears to be in its infancy with emerging and evolving norms, standards and platforms, (Maas, 2010; Valenza, 2014) where one can only wonder who the winners and losers will be.

Factors around design and publication

There are economic issues of efficiency, resource and time wastage as many individual teachers with varying levels of capability; capacity; understanding and access to tools attempt to participate in the creation of materials (Bailey, 2014b). One issue is the absence of a clearing house or “store” such as “Teachers pay Teachers” (Teachers Pay Teachers, 2014) or “Teacher created Resources” (Teacher Created Resources, 2014) so the discovery of relevant material remains serendipitous and local. For example, YouTube abounds with “educational” material, but lacks a rating system appropriate for educational quality control including checking for producer bias.

For digital curriculum based material, critical mass, economies of scale, and the integration of pedagogy, design and technical tools and marketing are needed which puts educational publishers or organisation such as TED Education (Ted-ed, n.d.) rather than individual educators in a strong position to take control of this arena.

Copyright, Digital rights, licensing

There are issues around digital rights, rights management, copyright and the like, both for the creator and the consumer of digital products for the classroom. Cost and ownership is a tricky area as many products are leased rather than purchased, are platform captive and access to full text for students with disabilities may be precluded (Michaud, 2013; O’Brein, Gasser, & Palfrey, 2012; Puckett, 2010).

Conclusion

At the end of following this course, it could be suggested that the course name “Literature in Digital Environments” is a misnomer (Bailey, 2014a), and “Literacy in Digital Environments” could be an alternative title to encompass all the aspects of this rich arena.

References:

Alexander, B. (2011). Storytelling: A tale of two generations (Chapter 1). In The new digital storytelling: creating narratives with new media (pp. 3–15). Santa Barbara, California: Praeger.

Anstey, M., & Bull, G. (2012). Using multimodal factual texts during the inquiry process. PETAA, 184, 1–12. Retrieved from http://chpsliteracy.wikispaces.com/file/view/PETAA+Paper+No.184.pdf

Bailey, N. (2014a, August 20). When is it digital literature? [Web Log post]. Retrieved October 12, 2014, from http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/informativeflights/2014/08/20/when-is-it-digital-literature/

Bailey, N. (2014b, September 10). Module 4.1: What questions or answers do you have in relation to digital storytelling? [Web log post]. Retrieved October 12, 2014, from http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/informativeflights/2014/09/10/module-4-1-what-questions-or-answers-do-you-have-in-relation-to-digital-storytelling/

Bailey, N. (2014c, September 30). Assessment item 7: Blog 4 – Electronic media and the nature of the story [Web log post]. Retrieved October 12, 2014, from http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/informativeflights/2014/09/30/assessment-item-7-blog-4-electronic-media-and-the-nature-of-the-story/

Botturi, L., Bramani, C., & Corbino, S. (2012). Finding Your Voice Through Digital Storytelling. TechTrends, 56(3), 10–11. doi:10.1007/s11528-012-0569-1

Bowler, L., Morris, R., Cheng, I.-L., Al-Issa, R., & Leiberling, L. (2012). Multimodal stories: LIS students explore reading, literacy, and library service through the lens of “The 39 Clues.” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 53(1), 32–48.

Coleborne, C., & Bliss, E. (2011). Emotions, Digital Tools and Public Histories: Digital Storytelling using Windows Movie Maker in the History Tertiary Classroom. History Compass, 9(9), 674–685. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00797.x

Dockter, J., Haug, D., & Lewis, C. (2010). Redefining Rigor: Critical Engagement, Digital Media, and the New English/Language Arts. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(5), 418–420. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ871723&site=ehost-live

Edwards, J. T. (2013). Reading Beyond the Borders: Observations on Digital eBook Readers and Adolescent Reading Practices. In J. Whittingham, S. Huffman, W. Rickman, & C. Wiedmaier (Eds.), Technological Tools for the Literacy Classroom: (pp. 135–158). IGI Global. Retrieved from http://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/978-1-4666-3974-4

Goodwin, B. (2013). The Reading Skills Digital Brains Need. Educational Leadership, 71(3), 78. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=91736083&site=ehost-live

Gottschall, J. (2012, May 2). Why Storytelling Is The Ultimate Weapon. Retrieved September 29, 2014, from http://www.fastcocreate.com/1680581/why-storytelling-is-the-ultimate-weapon

Green, M. C., Brock, T. C., & Kaufman, G. F. (2004). Understanding Media Enjoyment: The Role of Transportation Into Narrative Worlds. Communication Theory, 14(4), 311–327. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00317.x

Hall, T. (2012). Digital Renaissance: The Creative Potential of Narrative Technology in Education. Creative Education, 03(01), 96–100. doi:10.4236/ce.2012.31016

Jabr, F. (2013, April 11). The Reading Brain in the Digital Age: The Science of Paper versus Screens [Article]. Retrieved August 31, 2014, from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reading-paper-screens/

King, K., & Fogle, L. (2006). Bilingual Parenting as Good Parenting: Parents’ Perspectives on Family Language Policy for Additive Bilingualism. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(6), 695–712. doi:10.2167/beb362.0

Kingsley, K. V. (2007). Empower Diverse Learners With Educational Technology and Digital Media. Intervention in School & Clinic, 43(1), 52–56. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=26156207&site=ehost-live

Leacock, T. L., & Nesbit, J. C. (2007). A Framework for Evaluating the Quality of Multimedia Learning Resources. Educational Technology & Society, 10(2), 44–59.

Maas, D. (2010, June). Web-based Digital Storytelling Tools and Online Interactive Resources [Web Log]. Retrieved from http://maasd.edublogs.org/files/2010/06/Web-based-Digital-Storytelling-Tools-Online-Interactives-2gwjici.pdf

Margolin, S. J., Driscoll, C., Toland, M. J., & Kegler, J. L. (2013). E-readers, Computer Screens, or Paper: Does Reading Comprehension Change Across Media Platforms?: E-readers and comprehension. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27(4), 512–519. doi:10.1002/acp.2930

Matthews, J., RGN BSc PG Dip. (2014). Voices from the heart: the use of digital storytelling in education. Community Practitioner, 87(1), 28–30. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1474889132?accountid=10344

Michaud, D. (2013). Copyright and Digital Rights Management: Dealing with artificial access barriers for students with print disabilities. Feliciter, 59(1), 24–30. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/docview/1286679756?accountid=10344

Nokelainen, P. (2006). An empirical assessment of pedagogical usability criteria for digital learning material with elementary school students. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 9(2), 178–197. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=85866426&site=ehost-live

O’Brein, D., Gasser, U., & Palfrey, J. G. (2012, July 1). E-Books in Libraries: A Briefing Document Developed in Preparation for a Workshop on E-Lending in Libraries. Berkman Center Research Publication No. 2012-15. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2111396

Parrott, K. (2011, July 18). 5 Questions to Ask When Evaluating Apps and Ebooks [Web log post]. Retrieved August 31, 2014, from http://www.alsc.ala.org/blog/2011/07/5-questions-to-ask-when-evaluating-apps-and-ebooks/

Phillips, A. (2012). A creator’s guide to transmedia storytelling: how to captivate and engage audiences across multiple platforms. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Puckett, J. (2010). Digital Rights Management as Information Access Barrier. Progressive Librarian, Fall-Winter(34/35), 11–24. Retrieved from http://www.progressivelibrariansguild.org/PL_Jnl/pdf/PL34_35_fallwinter2010.pdf

Rhodes, J. A., & Milby, T. M. (2007). Teacher-Created Electronic Books: Integrating Technology to Support Readers With Disabilities. The Reading Teacher, 61(3), 255–259. doi:10.1598/RT.61.3.6

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1995). Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story. In R. S. Wyer (Ed.), Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story (Vol. VIII, pp. 1–85). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved from http://cogprints.org/636/1/KnowledgeMemory_SchankAbelson_d.html

Teacher Created Resources. (2014). Teacher Created Resources – Educational Materials and Teacher Supplies. Retrieved October 11, 2014, from http://www.teachercreated.com/

Teachers Pay Teachers. (2014). TeachersPayTeachers.com – An Open Marketplace for Original Lesson Plans and Other Teaching Resources. Retrieved October 11, 2014, from http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/

The Economist. (2014, October). The future of the book. Retrieved October 11, 2014, from http://www.economist.com/news/essays/21623373-which-something-old-and-powerful-encountered-vault

Unsworth, L. (2008). Multiliteracies, E-literature and English Teaching. Language and Education, 22(1), 62–75. doi:10.2167/le726.0

Valenza, J. (2014). The Digital Storytelling Tools Collection. Retrieved October 11, 2014, from https://edshelf.com/profile/joycevalenza/digital-storytelling-tools

Walker, S., Jameson, J., & Ryan, M. (2010). Skills and strategies for e-learning in a participatory culture (Ch. 15). In R. Sharpe, H. Beetham, & S. Freitas (Eds.), Rethinking learning for a digital age: How learners are shaping their own experiences (pp. 212–224). New York, NY: Routledge.

Walsh, M. (2010). Multimodal literacy: What does it mean for classroom practice? Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 33(3), 211–239.

Wolf, M., & Stoodley, C. J. (2008). Proust and the squid: the story and science of the reading brain. New York: Harper Perennial.

The point of literature

I absolutely couldn’t have said it better, so I’d like to share this movie by Marcus Armitage.

What is Literature for? from Marcus Armitage on Vimeo, animated by Marcus Armitage and Ignatz Johnson Higham.

Voice over Alain de Botton.

Assessment item 7: Blog 4 – Electronic media and the nature of the story

Electronic media are not simply changing the way we tell stories: they’re changing the very nature of story, or what we understand (or do not understand) to be narratives. To what extent is this true?

From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p6E8jpFasR0

Many authors have argued that storytelling is intrinsic to humanity (Schank & Abelson, 1995) and part of memory and learning. And yet for some reason it appears to me that storytelling had something of a hiatus in the last century, perhaps as a side effect of the post war modern corporate life, the emphasis on the scientific method and the space race. However the proliferation of research, writings and talks on the power of storytelling in all aspects of life from the scientific (Bailey, 2013) to the corporate (Gottschall, 2012) to education (Matthews, 2014) and everything in-between hints that storytelling is once again coming into its own (Pettitt, Donaldson, & Paradis, 2010; Sauerberg, 2009). Whether electronic media is a cause or an effect of this or whether it is just part of the zeitgeist is something we will only know in hindsight.

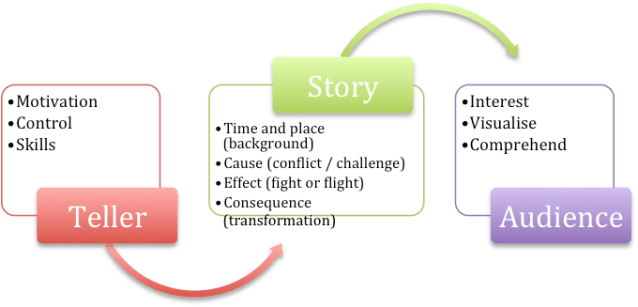

What we traditionally understand to be narrative consists of a storyteller, an audience and the narrative elements of a hero, a problem, an antagonist, tasks, a turning point and an outcome (Alexander, 2011). How electronic media is changing the nature of this is by broadening the concept of who is the storyteller. Once a digital narrative moves beyond being a story delivered electronically as in an eBook, or as a movie, but streamed or available digitally and goes to being an interactive “event” in which the distinction between the storyteller and the audience blurs and is interchangeable, one can talk about the nature of the narrative being changed by the media and its affordances. The creator becomes an initiator and the audience becomes collaborators and co-creators. The question then is whether one can still find the narrative elements back in this new hybrid creation? Does the participation of many voices enhance or hamper the profundity, meaning and emotion at the root of the narrative? Does engagement and involvement and participation equate to the “wisdom of crowds” or does it result in a “lowest common denominator” product? Are we moving from a period of finite works of infinite genius to infinite works of dubious merit (Pickett, 1986) – albeit a series of very clever and networked and buzzed works.

Another matter in all of this that is somewhat bothering me is the way in which the “science” of storytelling and its capacity to capture attention and emotion in its audience is being (ab)used for commercial purposes or to manipulate audiences to create changes in political (Simsek, 2012), social (Burgess & Vivienne, 2013; LaRiviere, Snider, Stromberg, & O’Meara, 2012) or public sphere (Poletti, 2011). Proponents would of course argue that the ends justify the means – but of course both sides of the debate have the same weapons in their arsenals (see the whole climate change narrative as an example of this), and as educators this makes our task of aiding the new generation of learners to be knowledgeable, discernable, informed and aware that much more important.

References:

Alexander, B. (2011). Storytelling: A tale of two generations (Chapter 1). In The new digital storytelling: creating narratives with new media (pp. 3–15). Santa Barbara, Calif: Praeger.

Bailey, P. (2013, March 27). Science Writing: You need to know how to tell a good story [Web log]. Retrieved September 29, 2014, from http://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/mar/27/penny-bailey-science-writing-wellcome

Burgess, J. E., & Vivienne, S. (2013). The remediation of the personal photograph and the politics of self-representation in digital story- telling. Journal of Material Culture, 18(3), 279–298. Retrieved from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/62708/

Gottschall, J. (2012, May 2). Why Storytelling Is The Ultimate Weapon. Retrieved September 29, 2014, from http://www.fastcocreate.com/1680581/why-storytelling-is-the-ultimate-weapon

LaRiviere, K., Snider, J., Stromberg, A., & O’Meara, K. (2012). Protest: Critical lessons of using digital media for social change. About Campus, 17(3), 10–17. doi:10.1002/abc.21081

Matthews, J., RGN BSc PG Dip. (2014). Voices from the heart: the use of digital storytelling in education. Community Practitioner, 87(1), 28–30. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1474889132?accountid=10344

Pettitt, T., Donaldson, P., & Paradis, J. (2010, April 1). The Gutenberg Parenthesis: oral tradition and digital technologies. Retrieved August 29, 2014, from http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/forums/gutenberg_parenthesis.html

Pickett, D. (1986). What is literature – established canon or popular taste? English Today, 2(01), 37. doi:10.1017/S0266078400001735

Poletti, A. (2011). Coaxing an intimate public: Life narrative in digital storytelling. Continuum, 25(1), 73–83. doi:10.1080/10304312.2010.506672

Sauerberg, L. O. (2009). The Encyclopedia and the Gutenberg Parenthesis. In Media in Transition 6: stone and papyrus, storage and transmission (pp. 1–13). Cambridge, MA, USA.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (1995). Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story. In R. S. Wyer (Ed.), Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story (Vol. VIII, pp. 1–85). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Retrieved from http://cogprints.org/636/1/KnowledgeMemory_SchankAbelson_d.html

Simsek, B. (2012). Using Digital Storytelling as a change agent for women’s participation in the Turkish Public Sphere (Doctor of Philosophy). Queensland University of Technology, Queensland, Australia. Retrieved from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/50894/1/Burcu_Simsek_Thesis.pdf