I subscribe to way too many Facebook groups. I need to stop it actually, they’ve become like women’s magazines. But worse. You keep seeing the same things come up over and over again, but instead of ignoring them you can actually have a say, which is giving yourself the delusion of helpfulness, but actually the smartest person in the room of Facebook groups is not the room itself, to misquote David Weinberger.

Some of the smartest people I know don’t do Facebook and when they do, they’re lurkers not participators. So I guess that’s making me stupid. I just can’t help myself because the fact that someone may actually genuinely want an accurate answer AND follow up is illusionary enough to put up with the ignorance of echo-chambers and the chance that you may learn something.

No where is worse than education groups, and within those groups nothing is worse than questions and answers about bilingualism and language. Except perhaps dinner parties between parents of children of roughly the same age that are excruciating examples of passive aggressive one-upmanship. Right now the sum of my parenting advice can be summed up as:

- It’s hard to kill a baby (i.e. CTFD)

- Regularity, sleep and reading (and don’t be too poor)

- Avoid dinner parties with other parents unless their children are at least 10 years older than yours

- Pick two languages and give them all you’ve got

It’s the last point I’d like to write about today. On one of the groups the following was posted:

2yr old (born NOV 2015) who is trilingual (if you can even say this about a 2yr old). German mum, French dad, English spoken with nanny and language between parents. I’m looking for kindergarten options from around next summer … have no idea where to start.

No preference towards public/private or towards any language even though I’m wondering if adding mandarin might be a bit confusing given that there are already the other 3. What do you think? Focus is more on play/social activities rather than academics

This is a pretty typical question and the answers were also pretty typical – a combination of shouting out school names that have either French or German, alternating with saying that children can easily learn any amount of languages (the number 12 was even suggested), compared with humblebrags about how “fluent” their 5 year old was in any number of languages.

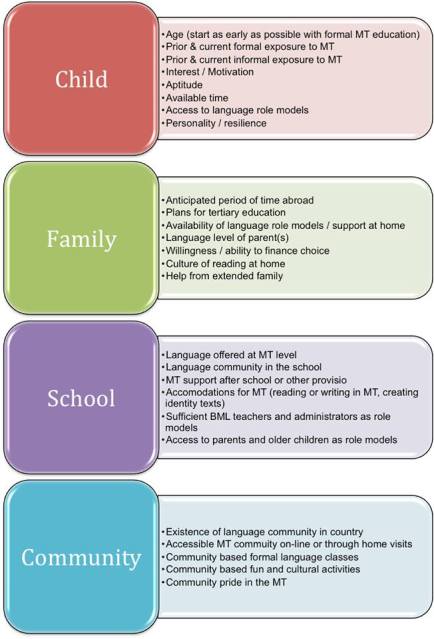

I must admit to entering the fray and suggesting that they chose the language of the school based on their future plans if known – i.e. go back to a French / German speaking environment or continue in the international sphere, and based on who would be at home to support the homework and reading. And to choose 2 languages and do them properly. There are language experts who can help people on this. There are books and research papers written on this. And don’t ask parents of young children – they know not what they say. Don’t even talk to educators in primary schools. speak to parents with teenagers, preferably at the point where they have to choose their IB language. Talk to teenagers, and talk to teachers of IB languages.

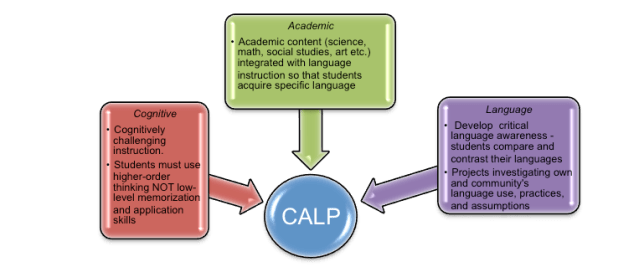

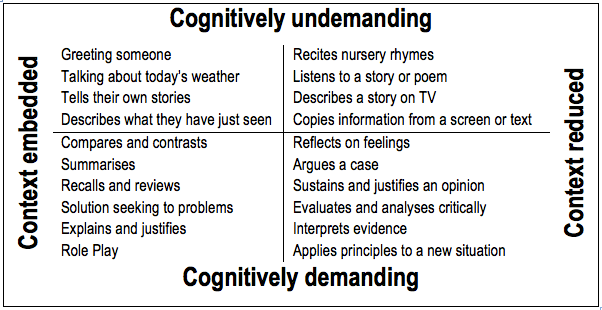

Being bilingual is NOT just speaking a language. It is reading and writing. Being literate. And that takes formal lesson time, time spent reading and writing AT grade level. There are so many barriers to that. I’m now talking general international schools, of course there are exceptions / bilingual schools. If you’re lucky you’ll get 40 minutes a day in the language at school. Probably in that language as a SECOND language, i.e. language learning may just be a combination of groundhog day (learning the same things year after year) and/or teaching to the lowest common denominator. So you’re going to have to supplement at home. Either by classes in the afternoon / weekends, online or with a tutor. Besides having to read to and with your child in that language. And dedicate at least part of your holidays to immersion in that language environment. As one expert who recently visited our school said “language is not buy one, get one free”. My personal statement is always “you don’t learn a language by breathing the same air as others who speak it”. Bottom line is it takes planning, time and money.

As I write (Saturday afternoon) my husband is in my son’s room reading in Dutch with him. He’s 14. He has in-school after hours Dutch classes for 3 hours a week plus out-of-school additional tutoring for about 2 hours a week / fortnight depending on his needs. According to his Dutch teacher there are many students who cannot enter the program as the level of their “literate” Dutch is too low. And many of the students in the program are doing Dutch at a much lower level than their chronological age. We took action when he was 9 and started intensive work on his Dutch after he was failing at Chinese. It’s been expensive and time-consuming but he’s on track for a bilingual diploma plus he can communicate with his Dutch family and if necessary could student there in Dutch at university level.

My daughter thrived in the bilingual English-Chinese environment in Hong Kong, hated the only alternative of Chinese second language at her primary school, Had me nagging her to continue reading and writing chinese in her spare time with a tutor until middle school, got into the native stream for middle school / iGCSE where she’s the only caucasian / non-Chinese-heritage child left in a class of about 8 students only. This is only because she’s an exceptionally diligent child and kept up her reading and writing. She bemoans the low expectations and standards at school. Most of the students in her class are only doing Chinese on the insistence of their parents. She may do first language IB and has been recommended for it, but has lost motivation.

All of my French friends who have had children come up the system internationally have, to their regret, children doing French second language.

If you’re interested in reading more on this topic, I’ve read, thought and written reams about it.