Here is the presentation I gave at the Bangkok Librarian workshare last weekend. Basically my argument is we shouldn’t start our conversations on information literacy with the choice of which model we’ll employ, but should take a step back to what our philosophy of learning is, ….. read more

Category: ETL401

Professional Blog for ETL401_201490

Critical Reflection ETL401

In this course, what I have learnt in the library and information sphere is now placed in the context of the school library, which is where I hope to further my career. In doing so it has clarified and added detail to concepts such as the role of the teacher librarian (TL) and information literacy (IL), while making me aware of what I don’t know much about – particularly in the area of curriculum and learning theories. As such, I am in a slightly stronger position meta-cognitively in ‘knowing what I don’t know’ (Morris, 2010). The comments of my fellow students and the course co-ordinator in the online fora, who come from a teaching background have been invaluable in this respect.

The role of the teacher librarian is complex, multi-faceted and dependent on the school context – which I explored in my first blog post (Bailey, 2014). As I work in a large K-12 international school means that some of the roles are assumed by or shared with the literacy and digital literacy coaches, leading to the need for constant collaboration and partnership not only with classroom teachers, school leadership and administrators but also these coaches.

Evidence and accountability in our role is something I would like to explore further in my work, particularly as we start up new initiatives such as classroom libraries and continue existing work in creating library pathfinders and co-teaching in some humanities models. In this way we can ensure that we are strategic in our time and resource planning to optimise our efficacy.

One of the main themes of this course has been information literacy, where we were introduced to the main thought leaders in this area, including Kuhlthau (2010; 2012a, 2012b, 2012c), Herring (2011; Herring, Tarter, & Naylor, 2002), and Eisenberg (2008; Wolf, Brush, & Saye, 2003). While many of the models of information literacy focus on the scaffolding of skills, information literacy can be seen as having four dimensions: cognitive (skill based); meta-cognitive (reflective); affective (positive and negative emotions); and the socio-cultural, including digital citizenship and ethical use of information (Kong & Li, 2009; Kuhlthau, 2013; Waters, 2012). This, and the question of transferability is something I explored in my blog discussing why information literacy is more than a set of skills (Bailey, 2015b). Literacy convergence and the 21st Century learner are valid realities that rethink the ambit of literacy in an information society that doesn’t only rely on text, and has expectations for learners that go beyond the personal consumption of information to contributing to using knowledge for personal or social transformation (Bailey, 2015a). However they can also be used as buzz words that can obfuscate the essence of information literacy irrespective of the medium used for access and dissemination of information (Crockett, 2013).

Learning naturally goes on outside the (virtual) classroom, and I have learnt a considerable amount through attending TL conferences, work shares, knowledge exchange workshops and conversations with my peers and more experienced TLs. One such conversation led to me investigating the fascinating concept of Threshold Concepts, particularly as it relates to information literacy (Hofer, Townsend, & Brunetti, 2012; Tucker, Weedman, Bruce, & Edwards, 2014). Although most research is currently in tertiary education (Flanagan,2015) I would like to explore which concepts would be relevant for our students and at what level we could introduce them and the most effective activities to do so. I’d also like to investigate assessment tools to aid us in pinpointing the problematic concepts in new students who have not come through the Guided Inquiry process of the school.

Our collaboration is not just with students, teachers and administrators but also parents who are often the ones picking up the slack and tasked with helping frustrated children with assignments or homework (Hoover‐Dempsey et al., 2005; Kong & Li, 2009). I have started doing some outreach to parents through co-ordinating our parent volunteer program, and marketing our online resources but realise I can do far more in educating parents in IL concepts and how best to continue scaffolding these concepts at home and making them aware of how our resources can aid them in this process.

One of the most valuable parts of this course was gaining an understanding of my own learning including cognitive and affective processes in the past two years and reflecting on my attempts to go through this process effectively unscaffolded, relying on instinct and common sense! Perhaps my learning would have been more efficient and effective if I’d known this all at the start, but certainly now I will be better at passing on the knowledge and experience to my students and children.

References:

Bailey, N. (2014, December 7). ETL401 Blog Task 1: The role of the TL in schools [Web Log]. Retrieved January 24, 2015, from http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/informativeflights/2014/12/07/etl401-blog-task-1-the-role-of-the-tl-in-schools/

Bailey, N. (2015a, January 4). The role of the TL in practise with regard to the convergence of literacies in the 21st Century [Web Log]. Retrieved January 24, 2015, from http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/informativeflights/2015/01/04/the-role-of-the-tl-in-practise-with-regard-to-the-convergence-of-literacies-in-the-21st-century/

Bailey, N. (2015b, January 18). Blog task 3: Information Literacy is more than a set of skills [Web Log]. Retrieved January 24, 2015, from http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/informativeflights/2015/01/18/blog-task-3-information-literacy-is-more-than-a-set-of-skills/

Crockett, L. (2013, February 28). Literacy is NOT Enough: 21st Century Fluencies for the Digital Age [Streaming Video]. Retrieved January 4, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8DEeR1sraA

Eisenberg, M. B. (2008). Information Literacy: Essential Skills for the Information Age. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 28(2), 39–47.

Flanagan, M. (2015, January 21). Threshold Concepts: Undergraduate Teaching, Postgraduate Training and Professional Development. A short introduction and bibliography [Website]. Retrieved January 25, 2015, from http://www.ee.ucl.ac.uk/~mflanaga/thresholds.html

Herring, J. E. (2011). Assumptions, Information Literacy and Transfer in High Schools. Teacher Librarian, 38(3), 32–36.

Herring, J. E., Tarter, A.-M., & Naylor, S. (2002). An evaluation of the use of the PLUS model to develop pupils’ information skills in a secondary school. School Libraries Worldwide, 8(1), 1.

Hofer, A. R., Townsend, L., & Brunetti, K. (2012). Troublesome Concepts and Information Literacy: Investigating Threshold Concepts for IL Instruction. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 12(4), 387–405. doi:10.1353/pla.2012.0039

Hoover‐Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M. T., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., & Closson, K. (2005). Why Do Parents Become Involved? Research Findings and Implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 105–130. doi:10.1086/499194

Kong, S. C., & Li, K. M. (2009). Collaboration between school and parents to foster information literacy: Learning in the information society. Computers & Education, 52(2), 275–282. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2008.08.004

Kuhlthau, C. C. (2013, October). Information Search Process [Website]. Retrieved from http://comminfo.rutgers.edu/~kuhlthau/information_search_process.htm

Kuhlthau, C. C., & Maniotes, L. K. (2010). Building Guided Inquiry Teams for 21st-Century Learners. School Library Monthly, 26(5), 18.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2012a). Assessment in guided inquiry. In Guided inquiry design: a framework for inquiry in your school (pp. 111–131). Santa Barbara, California: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2012b). Guided inquiry design: a framework for inquiry in your school. Santa Barbara, California: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari, A. K. (2012c). The research behind the design. In Guided inquiry design: a framework for inquiry in your school (pp. 17–36). Santa Barbara, California: Libraries Unlimited.

Morris, E. (2010, June 20). The Anosognosic’s Dilemma: Something’s Wrong but You’ll Never Know What It Is (Part 1). Retrieved February 4, 2014, from http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/the-anosognosics-dilemma-1/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=1

Tucker, V. M., Weedman, J., Bruce, C. S., & Edwards, S. L. (2014). Learning Portals: Analyzing Threshold Concept Theory for LIS Education. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 55(2), 150–165.

Waters, J. K. (2012, September 4). Turning Students into Good Digital Citizens. Retrieved January 2, 2015, from http://thejournal.com/Articles/2012/04/09/Rethinking-digital-citizenship.aspx

Wolf, S., Brush, T., & Saye, J. (2003). The Big Six Information Skills As a Metacognitive Scaffold: A Case Study. School Library Media Research, 6, 1–24. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/aaslpubsandjournals/slr/vol6/SLMR_BigSixInfoSkills_V6.pdf

Thought experiments and information literacy

A little while back KDA (Librarian Edge), enthusiastically placed a book on my desk and said I had to read it and I had to create a library guide based on it (I did, see this, and it was very enthusiastically received by Mr. Fleischman). She was completely right. What a wonderful resource has been placed into the hands of librarians and teachers everywhere. Read more ….

Blog task 3: Information Literacy is more than a set of skills

The question of whether information literacy (IL) is more than a set of skills is an important one, as it sets the philosophical basis that informs the approach that an institution and its administrators, teachers and teacher librarians (TL) take in the design and implementation of a program.

IL can probably thought as occurring along a continuum of proficiency, dependent on a number of factors including but not limited to:

- Age / developmental stage of the student (Brown, 2004; Miller, 2011)

- Psychological, attitudinal and motivational factors including resilience, persistence, ability to deal with ambiguity, complexity and emotion (American Association for School Librarians, 2007; Kuhlthau & Maniotes, 2010)

- Aptitudes such as prior knowledge, comprehension, interpretation and connection seeking (Herring & Bush, 2011)

- Social, linguistic and cultural context (Dorner & Gorman, 2012)

Drawing on my interest in language acquisition and particularly the field of bilingualism, I think an argument can be made for comparing IL and bilingualism. Cummins (1998, 2001, 2003) distinguishes between Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP). Students who have BICS appear to be fluent in the language, however, although they have developed the surface skills of speaking and listening, they lack the ability to succeed in cognitively demanding context-reduced academic tasks. Research indicated that BICS could be acquired in a couple of years, while CALP took five to seven years. Similarly it could be argued that the superficial skills of IL could be acquired reasonably rapidly within context embedded, concrete tasks that are sufficiently scaffolded by the teacher or TL. However, researchers have observed the sometimes elusive ability of students to internalise information literacy instruction, and employ or transfer it across different learning contexts, depending on assumptions made by the learning community (Herring, 2011) even if IL instruction occurs embedded in Guided Inquiry (GI) (Thomas, Crow, & Franklin, 2011). In any event, it would appear that this internalization and transfer of skills did not occur until the high school years – indicating that it is a process that occurs over time and as a result of repeated exposure to and use of IL skills in increasingly complex and abstract learning tasks.

It can be posited that one could look at the students coming out of an institution and employ a retroactive deduction on whether their institution considers IL to merely be a set of skills rather than considering its aspects of transformational process (Abilock, 2004), a learning practice (Lloyd, 2007, 2010 cited in Herring, 2011) or a construct that goes beyond personal learning of content or concept but also encompasses aspects of digital citizenship (Waters, 2012) and the participatory culture of knowledge (O’Connell, 2012).

To conclude, I still have many questions in the context of school based instruction and acquisition of IL. Does it become self-limiting by the assumptions and process by which it is taught? How far does the school system allow students to progress? If one treats IL as a skill – what would motivate a student to go beyond superficial skill acquisition and apparent information fluency and by going through the motions of pre-determined scaffolds and questions to the point of internalization and deeper learning?

References

Abilock, D. (2004). Information literacy: An overview of design, process and outcomes. Retrieved from http://www.noodletools.com/debbie/literacies/information/1over/infolit1.html

American Association for School Librarians. (2007). Standards for the 21st-Century Learner. AASL. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/standards-guidelines/learning-standards

Brown, A. (2004). Reference services for children: information needs and wants in the public library. The Australian Library Journal, 53(3), 261–274.

Cummins, J. (1998). Immersion education for the millennium: What have we learned from 30 years of research on second language immersion? In M. R. Childs & R. M. Bostwick (Eds.), Learning through two languages: Research and practice (pp. 34–47). Katoh Gakuen, Japan.

Cummins, J. (2001). Bilingual Children’s Mother Tongue: Why Is It Important for Education? Retrieved May 27, 2014, from http://iteachilearn.org/cummins/mother.htm

Cummins, J. (2003). Putting Language Proficiency in Its Place: Responding to Critiques of the Conversational – Academic Language Distinction. Retrieved May 27, 2014, from http://iteachilearn.org/cummins/converacademlangdisti.html

Dorner, D. G., & Gorman, G. E. (2012). Developing Contextual Perceptions of Information Literacy and Information Literacy Education in the Asian Region. In A. Spink & D. Singh (Eds.), Library and information science trends and research Asia-Oceania (pp. 151–172). Bingley, U.K.: Emerald. Retrieved from http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=862261

Herring, J. E. (2011). Assumptions, Information Literacy and Transfer in High Schools. Teacher Librarian, 38(3), 32–36.

Herring, J. E., & Bush, S. J. (2011). Information literacy and transfer in schools: implications for teacher librarians. Australian Library Journal, 60(2), 123–132.

Kuhlthau, C. C., & Maniotes, L. K. (2010). Building Guided Inquiry Teams for 21st-Century Learners. School Library Monthly, 26(5), 18.

Miller, P., H. (2011). Piaget’s Theory Past, Present, and Future. In U. C. Goswami (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development (pp. 649–672). Chichester; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

O’Connell, J. (2012). Change has arrived at an iSchool library near you. In Information literacy beyond library 2.0 (pp. 215–228). London: Facet.

Thomas, N. P., Crow, S. R., & Franklin, L. L. (2011). The Information Search Process – Kuhlthau’s Legacy. In Information literacy and information skills instruction: applying research to practice in the 21st century school library (3rd ed., pp. 33–58). Santa Barbara, Calif: Libraries Unlimited.

Waters, J. K. (2012, September 4). Turning Students into Good Digital Citizens. Retrieved January 2, 2015, from http://thejournal.com/Articles/2012/04/09/Rethinking-digital-citizenship.aspx

The role of the TL in practise with regard to the convergence of literacies in the 21st Century

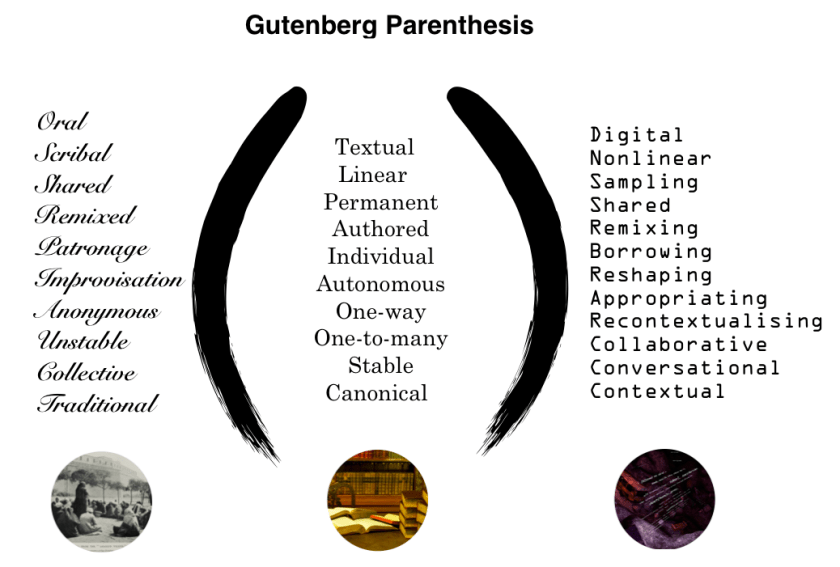

In what authors are referring to as the post Gutenberg parenthesis society, (Kenny, 2011; Pettitt, Donaldson, & Paradis, 2010), an emphasis on textual literacy is no longer sufficient. Shifts in technology, particularly with the advent of Web 2.0 and its social media affordances mean that literacy has become a dynamic and multifaceted concept that goes beyond information literacy but incorporates digital, visual, media and a multitude of other literacies under the umbrella term multi-literacy (Mackey & Jacobson, 2011). Trans-literacy as a concept, attempts to map meaning and interaction across these literacies and different media, including social media (Ipri, 2010).

O’Connell (2012) suggests the teacher librarian (TL) respond along three strategic dimensions. Firstly through an involvement strategy whereby the TL “meets students where they are”, secondly with a responsive information strategy that filters, curates, and shares content and finally through a leadership strategy by taking leadership in curriculum, broaching the digital divide, championing digital citizenship and global sharing. While she encourages TL’s to create a personal learning environment (PLE), utilize their personal learning network (PLN) and personal web tools (PWT), it can be posited that the TL has to go beyond creating and using these tools personally, but to ensure educators and students in the community can also tap into their power.

Information literacy concerns itself with the selection, evaluation and use of information to solve a problem or research question, however, trans-literacy goes beyond this paradigm to the creation and sharing of ideas and the importance of social connections. Besides constructivism, the TL should incorporate principles of connectivism in their teaching approach, emphasizing the connections between the individual, data and others in the current networked culture (McBride, 2011). This principle is wonderfully illustrated by Joyce Valenza in her video “See Sally Research” (Valenza, 2011), which also highlights the importance of TLs creating an environment in which students go beyond using information for personal research but as a means of expressing themselves as digital citizens. Waters (2012) expounds on the theme of digital citizenship and rightly points out that this should go beyond behaviours and prohibitions creating a safe and civil digital environment but that TLs should encourage their students to participate as producers and managers of information and perspectives in a globally socially responsible manner.

In their book “Literacy is not enough”, Crockett, Jukes and Church (2011) create a conceptual model incorporating information, solution, creativity, collaboration and media fluency and provide the educator or TL with suggested processes and scaffolds for teaching each (reviewed by Loertscher & Marcoux, 2013). In his talk, Lee Crockett emphasizes that these fluencies are important to the 21st-Century learner independent of the amount of digital technology employed, something that is often neglected when technology dominates the conversations (Crockett, 2013).

As TLs we need to be aware of all these discussions around the various iterations of literacies as well as taking leadership in our learning environments and ensuring our teaching and assessments follow the latest standards where these are available.

References:

Crockett, L. (2013, February 28). Literacy is NOT Enough: 21st Century Fluencies for the Digital Age [Streaming Video]. Retrieved January 4, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N8DEeR1sraA

Crockett, L., Jukes, I., & Churches, A. (2011). Literacy is not enough: 21st-century fluencies for the digital age. Kelowna, B.C. : Thousand Oaks, Calif.: 21st Century Fluency Project ; Corwin.

Ipri, T. (2010). Introducing transliteracy: What does it mean to academic libraries? College & Research Libraries News, 71(10), 532–567. Retrieved from http://crln.acrl.org/content/71/10/532.short

Kenny, R. F. (2011). Beyond the Gutenberg Parenthesis: Exploring New Paradigms in Media and Learning. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 3(1), 32–46. Retrieved from http://www.jmle.org

Loertscher, D. V., & Marcoux, E. (2013). Literacy is not enough: 21st-century fluencies for the digital age. Teacher Librarian, 40(3), 42–42,71.

Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. E. (2011). Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy. College & Research Libraries, 72(1), 62–78. doi:10.5860/crl-76r1

McBride, M. F. (2011). Reconsidering Information Literacy in the 21st Century: The Redesign of an Information Literacy Class. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 40(3), 287–300.

O’Connell, J. (2012). Change has arrived at an iSchool library near you. In Information literacy beyond library 2.0 (pp. 215–228). London: Facet.

Pettitt, T., Donaldson, P., & Paradis, J. (2010, April 1). The Gutenberg Parenthesis: oral tradition and digital technologies. Retrieved August 29, 2014, from http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/forums/gutenberg_parenthesis.html

Valenza, J. (2011). See Sally Research @TEDxPhillyED [Streaming Video]. Retrieved May 22, 2014, from http://blogs.slj.com/neverendingsearch/2011/09/05/see-sally-research-tedxphillyed/

Waters, J. K. (2012, September 4). Turning Students into Good Digital Citizens. Retrieved January 2, 2015, from http://thejournal.com/Articles/2012/04/09/Rethinking-digital-citizenship.aspx

Role of the TL trends and more assignment

I’m in the process of complete immersion and drowning in information, data points, ideas, readings literature, to do my latest assignments. I’ve been trying mind mapping – does that make any sense? It does to me it’s life the universe and everything of TLship. The issue is to translate that into 2500 words, no more no less appropriately referenced.

I also have other stuff. Lots and lots of other stuff. Way too much stuff. Like the matrix I made of all the issues around being a TL. Beautifully referenced even.

| Issue | Implication | Response |

| Demographic shift to students with more linguistic and cultural diversity (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013; “Canadian Demographics at a Glance: Some facts about the demographic and ethnocultural composition of the population,” n.d.; Center for Public Education, 2012; Ho, 2011) | Issues around equity and access to learning and resources (Mestre, 2009)Teaching strategies to address strengths and needs of students (Australian School Library Association, 2014) | Resources, staffing and collections necessary to reflect diversity of students and scaffold to language of instruction (Center for Public Education, 2012) |

| CCSS and other centrally determined standards and assessment (Dow, 2013; Lewis & Loertscher, 2014)

Emphasis on testing / learning outcomes (Weaver, 2010) |

Need strategies and deep understanding of standardsProvide teacher support & student instruction

TL should show how their existence enhances testing / learning outcomes

|

10 initiatives to put library at center of learning (Lewis & Loertscher, 2014)Content and inquiry skills support opportunities by TL (Todd, 2012)

Examine ways to integrate resources / tools in teacher in learning Extend textbook Teach IL – retrieval / search terms Tap into discussion at national and professional level Librarian as co-teacher with curriculum overview Show importance of reading to academic success Focus on learner needs

|

| Budgetary constraints coupled with under-estimating value of TL (Weaver, 2010)

Return on Investment (ROI) for TL needs to be evident (Gillespie & Hughes, 2014) |

Staffing shifted to teachers, aides, or librarians rather than teacher librarians

Accountability and evidence based practice

|

Reconsider time and priority managementMaximize opportunity for adding value

Outsource / terminate or streamline activities not focused on learner needs Provide qualitative and quantitative evidence of impact |

| Only librarian at a school (Valenza, 2011) | Cannot fulfil all aspects of role / spread thin across school | Mastery of publishing platforms to enhance website and web-based path-finders |

And how about the current and future trends? All there.

| Trend | Implication | TL response |

| Shift to inquiry based learning / project based learning / resource based learning (Boss & Krauss, 2007) | Curriculum resourcing needs to be more sophisticatedLearning not limited by time or space | Guide process with teachersCreate guides / pathways

Integrate technology Networks for meaningful collaboration |

| Technology integration in classrooms; BYOD; 1:1 programs (Everhart, Mardis, & Johnston, 2010; Johnston, 2012; Lagarde & Johnson, 2014)

Part of collection is digital (particularly non-fiction) Physical space (Lagarde & Johnson, 2014) |

LT’s need to have knowledge, skills and strategies to assume leadershipIssues with DRM (digital rights management), academic honesty, intellectual property,

Ethical and plagiarism issues due to ease of copying Information literacy becomes more important Use of space in library changes – fewer stacks more collaborative spaces; change in balance from “consumption” to “creation”

|

Lead / teach teachers and students, be positive role model / expertUnderstand DRM and IP

Ensure digital collection is visible Teach searching internet & databases Teaching and coaching academic honesty Rethink collection and space Shift to flexible teaching, meeting, collaborating and presentation space (Hay & Todd, 2010) Rethink promotion and display Think also about psychological space – not just physical (Todd, 2012)

|

5 Trends (International society for technology in Education)

|

Easy to be overwhelmed hard to discern what is effective / fits learning needs / goals | Know what is trending and what the implication is for teaching / learning / information literacyBe discerning, what is valuable / effective for learning

Network / make connections Deconstruct technology |

| Access to all and any information (Marcoux, 2014) | Possibility of students using irrelevant / incorrect or unsafe information | Information literacy instruction, separate, embedded in curriculum, learning themes, at every opportunity |

| Inter-textuality, transmediation and semiotics (Schmit, 2013)

Post literate society (Todd, 2012)

Gutenberg parenthesis (Pettitt, Donaldson, & Paradis, 2010)

Shift from Information literacy to meta-literacy (O’Connell, 2012b) |

Shift from text to other sign symbols (audio, spatial, visual, gestural, linguistic)

Change in type and media of collections

Adapt (information) literacy teaching

|

Literacy and text definition expanded to “architecture, art, dance, drama, mathematics, kinaesthetic, play, technology, and so forth,” (Schmit, 2013, p. 44), transmediation in curriculum and lesson planning, use of technology, digital storytelling. |

| Distance Learning / MOOC (Massive Open Online Courses)/ Professional learning communities (PLC) / Professional Learning Networks (PLN) and Communities of practice (COP) (Lagarde & Johnson, 2014) | Learning no longer bounded by time, space and location |

And all useless. Totally totally useless. I just can’t find a structure. I can’t find a thread, meaning, a theme, something to tie it all together. Something wonderful and powerful and amazing. It is too much. It’s probably enough for a dozen blog posts and 4 articles.

I know. Simplify. Stick to one or two things. Let the rest go. But I don’t have any clarity yet…

References:

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Australian Social Trends, April 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2014, from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features30April+2013

Australian School Library Association. (2014, January). Evidence Guide for Teacher Librarians in the Highly Accomplished Career Stage. Australian School Library Association.

Boss, S., & Krauss, J. (2007). Mapping the Journey – Seeing the Big Picture. In Reinventing Project Based Learning: Your Field Guide to Real-World Projects in the Digital Age (pp. 11–24). Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education. Retrieved from http://www.iste.org/images/excerpts/REINVT-excerpt.pdf

Canadian Demographics at a Glance: Some facts about the demographic and ethnocultural composition of the population. (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2014, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-003-x/2007001/4129904-eng.htm

Center for Public Education. (2012, May). The United States of education: The changing demographics of the United States and their schools. Retrieved December 14, 2014, from http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/You-May-Also-Be-Interested-In-landing-page-level/Organizing-a-School-YMABI/The-United-States-of-education-The-changing-demographics-of-the-United-States-and-their-schools.html

Dow, M. J. (2013). Meeting Needs: Effective Use of First Principles of Instruction. School Library Monthly, 29(8), 8–10. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=iih&AN=87773552&site=ehost-live

Everhart, N., Mardis, M. A., & Johnston, M. P. (2010). Diversity Challenge Resilience: School Libraries in Action. In Proceedings of the 12th Biennial School Library Association of Queensland. Brisbane, Australia: IASL.

Gillespie, A., & Hughes, H. (2014). Snapshots of teacher librarians as evidence-based practitioners [online]. Access, 28(3), 26–40. Retrieved from http://search.informit.com.au.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/documentSummary;dn=589128468876375;res=IELAPA

Hay, L., & Todd, R. (2010). School libraries 21C : the conversation begins. Scan, 29(1), 30–42. Retrieved from http://search.informit.com.au.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/fullText;dn=183676;res=AEIPT

Ho, C. (2011). “My School” and others: Segregation and white flight. Australian Review of Public Affairs, 10(1). Retrieved from http://www.australianreview.net/digest/2011/05/ho.html

Johnston, M. P. (2012). School Librarians as Technology Integration Leaders: Enablers and Barriers to Leadership Enactment. School Library Research, 15, 1–33. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=82442509&site=ehost-live

Lagarde, J., & Johnson, D. (2014). Why Do I Still Need a Library When I Have One in My Pocket? The Teacher Librarian’s Role in 1:1/BYOD Learning Environments. Teacher Librarian, 41(5), 40–44. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1548230103?accountid=10344

Lewis, K. R., & Loertscher, D. V. (2014). The Possible Is Now: The CCSS Moves Librarians to the Center of Teaching and Learning. Teacher Librarian, 41(3), 48–52,67. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1504428059?accountid=10344

Marcoux, E. “Betty.” (2014). When Winning Doesn’t Mean Getting Everything. Teacher Librarian, 41(4), 61–63. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1523915729?accountid=10344

Mestre, L. (2009). Culturally responsive instruction for teacher-librarians. Teacher Librarian, 36(3), 8–12. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA195325714&v=2.1&u=csu_au&it=r&p=EAIM&sw=w&asid=fc46665000eaf30a53c320a0b77bc226

O’Connell, J. (2012). Learning without frontiers: School libraries and meta-literacy in action. Access, 26(1), 4–7. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/934355007?accountid=10344

Pettitt, T., Donaldson, P., & Paradis, J. (2010, April 1). The Gutenberg Parenthesis: oral tradition and digital technologies. Retrieved August 29, 2014, from http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/forums/gutenberg_parenthesis.html

Schmit, K. M. (2013). Making the Connection: Transmediation and Children’s Literature in Library Settings. New Review of Children’s Literature and Librarianship, 19(1), 33–46. doi:10.1080/13614541.2013.752667

Todd, R. J. (2012). Visibility, Core Standards, and the Power of the Story: Creating a Visible Future for School Libraries. Teacher Librarian, 39(6), 8–14. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/ehost/detail/detail?sid=db2eaed5-c51c-48a2-adf5-8caa9a624d24%40sessionmgr113&vid=0&hid=115&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d

Valenza, J. (2011). Fully Loaded: Outfitting a Teacher Librarian for the 21st Century. Here’s What It Takes. School Library Journal, 57(1), 36–38. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/881456147?accountid=10344

Weaver, A. (2010). Teacher librarians: polymaths or dinosaurs? Access, 24(1), 18–19. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/219618343?accountid=10344

Gamification in the library

ETL401 Blog Task 1: The role of the TL in schools

The role of the teacher librarian (TL) can broadly be understood by looking at the elements of:

- Who we are

- Where we are

- What we need to know and

- What we need to do.

Who we are

To misquote Karl Menninger “What the teacher (librarian) is, is more important than what he teaches.” (“Karl A. Menninger Quote,” n.d.). It is the way in which individuals fulfil their role as TL that defines how both the profession and the individual is viewed. Aspects of this include strength of character (Bonanno, 2011), communication, cooperation, collaboration, interaction and relationships with those they come in contact with including students, teachers, principals and other members of the school community (Bonanno, 2011; Farmer, 2007; Gong, 2013; Lamb & Johnson, 2004a; Morris & Packard, 2007; Oberg, 2006, 2007; Valenza, 2010). Being a positive role model as a life long learner, inquirer and innovator with impeccable honesty and ethics is considered to be at the basis of who a TL is (Farmer, 2007; Lamb & Johnson, 2004b; Oberg, 2006; Valenza, 2010). Drawing from research in the corporate world, it would appear that likeability is more important than competence in fostering collaboration and working relationships (Casciaro & Lobo, 2005).

Where we are

The context within which the TL operates cannot be ignored (Bonanno, 2011; Morris & Packard, 2007). This includes the national educational or LIS (Library Information Science) ideology or systems and the background and personal experiences of all the school library stakeholders. Even within the relatively homogenous environment of a single country and culture, differences exist from school to school while in the context of an International school this can be amplified (Tilke, 2009).

When looking at the literature on school libraries in less developed economies, with single textbook, chalk and talk teaching methods, where there is an absence of policy and research, lack of specialist staff in either the teaching or librarian sphere, and a weak or neglected presence in the information society, (Abdullahi, 2009; Alomran, 2009; Odongo, 2009; Rengifo, 2009) the old Persian proverb “I cried because I had no shoes, until I met a man who had no feet” rings true.

What we need to know

The TL is expected to be a specialist both in teaching and in LIS. They need to combine knowledge, skills and experience in collection and resource management, information literacy, technology integration, curriculum and learning (Herring, 2007; Kaplan, 2007; O’Connell, 2012, 2014; Purcell, 2010; Valenza, 2010a). Various national and international professional organisations attempt to codify the skills and knowledge required in their standards and benchmarks for school librarians and set aspirational standards of excellence (ASLA, n.d.; “Australian School Library Association,” n.d., “International Association of School Librarianship – IASL,” n.d., “SLASA School Library Association of SA,” n.d.; IFLA, n.d.; Kaplan, 2007).

What we need to do

The core of what the TL does is advance school goals in an evidence based and accountable manner (Everhart, 2006; Farmer, 2007; Lamb & Johnson, 2004a; Oberg, 2002; R. Todd, 2003; R. J. Todd, 2007). The principal way in which these goals are achieved is through teaching and collaborating with other teachers (Herring, 2007; Purcell, 2010; Valenza, 2010). In addition, TLs managing people, resources and facilities (Everhart, 2006; Farmer, 2007; Tilke, 2009; Valenza, 2010).

In conclusion, the role of the TL is multi-faceted and dynamic as it continually adapts to the environment. In each of our individual contexts it is worth taking heed of S.I. Hayakawa’s comment that “Good teachers never teach anything. What they do is create the conditions under which learning takes place.” Those conditions are a combination of attitude, knowledge, skills and actions.

References

Abdullahi, I. (Ed.). (2009). Global library and information science: a textbook for students and educators: with contributions from Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East, and North America. München: K.G. Saur.

Alomran, H. I. (2009). Middle East: School libraries. In I. Abdullahi (Ed.), Global library and information science: a textbook for students and educators: with contributions from Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East, and North America (pp. 467–473). München: K.G. Saur.

ASLA. (n.d.). Standards of professional excellence for teacher librarians. Retrieved November 26, 2014, from http://www.asla.org.au/policy/standards.aspx

Australian School Library Association. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2014, from http://www.asla.org.au/

Bonanno, K. (2011). A profession at the tipping point: Time to change the game plan. Keynote speaker: ASLA 2011 [Vimeo]. Retrieved December 4, 2014, from https://vimeo.com/31003940

Casciaro, T., & Lobo, M. S. (2005). Competent Jerks, Lovable Fools, and the Formation of Social Networks. Harvard Business Review, 83(6), 92–100. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2005/06/competent-jerks-lovable-fools-and-the-formation-of-social-networks/ar/1

Everhart, N. (2006). Principals’ Evaluation of School Librarians: A Study of Strategic and Nonstrategic Evidence-based Approaches. School Libraries Worldwide, 12(2), 38–51. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lih&AN=24234089&site=ehost-live

Farmer, L. (2007). Principals: Catalysts for Collaboration. School Libraries Worldwide, 13(1), 56–65. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lih&AN=25545935&site=ehost-live

Gong, L. (2013). Technicality, humanity and spirituality – 3-dimensional proactive library service toward lifelong learning. Presented at the LIANZA Conference, Hamilton, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.lianza.org.nz/sites/default/files/Lidu%20Gong%20-%20Technicality%20humanity%20and%20spirituality%20-%203%20dimensional%20proactive%20library%20service%20toward%20lifelong%20learning.pdf

Herring, J. E. (2007). Teacher librarians and the school library. In S. Ferguson (Ed.), Libraries in the twenty-first century : charting new directions in information (pp. 27–42). Wagga Wagga, N.S.W: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

IFLA. (n.d.). IFLA/UNESCO School Library Manifesto. Retrieved November 26, 2014, from http://archive.ifla.org/VII/s11/pubs/manifest.htm

International Association of School Librarianship – IASL. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2014, from http://www.iasl-online.org/about/handbook/policysl.html

Kaplan, A. G. (2007). Is Your School Librarian “Highly Qualified”? Phi Delta Kappan, 89(4), 300–303. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=27757339&site=ehost-live

Karl A. Menninger Quote. (n.d.). Retrieved December 6, 2014, from http://izquotes.com/quote/290881

Lamb, A., & Johnson, L. (2004a, 2014). Library Media Program: Accountability. Retrieved November 25, 2014, from http://eduscapes.com/sms/program/accountability.html

Lamb, A., & Johnson, L. (2004b, 2014). Library Media Program: Evaluation. Retrieved November 25, 2014, from http://eduscapes.com/sms/program/evaluation.html

Morris, B. J., & Packard, A. (2007). The Principal’s Support of Classroom Teacher-Media Specialist Collaboration. School Libraries Worldwide, 13(1), 36–55. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lih&AN=25545934&site=ehost-live

Oberg, D. (2002). Looking for the evidence: Do school libraries improve student achievement? School Libraries in Canada, 22(2), 10–13+. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/222527406?accountid=10344

Oberg, D. (2006). Developing the respect and support of school administrators. Teacher Librarian, 33(3), 13–18. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/224879111?accountid=10344

Oberg, D. (2007). Taking the Library Out of the Library into the School. School Libraries Worldwide, 13(2), i–ii. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lih&AN=28746574&site=ehost-live

O’Connell, J. (2012). So you think they can learn. Scan, 31(May), 5–11. Retrieved from http://heyjude.files.wordpress.com/2006/06/joc_scan_may-2012.pdf

O’Connell, J. (2014). Researcher’s Perspective: Is Teacher Librarianship in Crisis in Digital Environments? An Australian Perspective. School Libraries Worldwide, 20(1), 1–19. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1543805459?accountid=10344

Odongo, R. I. (2009). Africa: School Libraries. In I. Abdullahi (Ed.), Global library and information science: a textbook for students and educators: with contributions from Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East, and North America (pp. 91–107). München: K.G. Saur.

Purcell, M. (2010). All Librarians Do Is Check Out Books, Right? A Look at the Roles of a School Library Media Specialist. Library Media Connection, 29(3), 30. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.csu.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=55822153&site=ehost-live

Rengifo, M. G. (2009). Latin America: School Libraries. In I. Abdullahi (Ed.), Global library and information science: a textbook for students and educators: with contributions from Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East, and North America. München: K.G. Saur.

SLASA School Library Association of SA. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2014, from http://www.slasa.asn.au/Advocacy/rolestatement.html

Tilke, A. (2009, September). Factors affecting the impact of a library and information service on the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme in an international school: A constructivist grounded theory approach. (A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy). Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, N.S.W.

Todd, R. (2003). Irrefutable evidence: how to prove you boost student achievement. (Cover Story). School Library Journal, 49(4), 52+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA100608794&v=2.1&u=csu_au&it=r&p=EAIM&sw=w&asid=194fea091c82b000bb3b69ca05004411

Todd, R. J. (2007). Evidenced-based practice and school libraries : from advocacy to action. In S. Hughes-Hassell & V. H. Harada (Eds.), School reform and the school library media specialist (pp. 57–78). Westport, CY: Libraries Unlimited.

Valenza, J. (2010, December). A revised manifesto [Web Log]. Retrieved May 21, 2014, from http://blogs.slj.com/neverendingsearch/2010/12/03/a-revised-manifesto/

Image Credits:

Teamwork: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/ba/Working_Together_Teamwork_Puzzle_Concept.jpg

Heart: https://openclipart.org/detail/-by-pianobrad-137125

World map: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/43/World_Map_Icon.svg

Knowledge: https://openclipart.org/image/300px/svg_to_png/184627/learn-icon.png

School Librarian Connection Conference Hong Kong

Over the weekend I was fortunate enough to attend some professional development in Hong Kong, SCHOOL LIBRARIAN CONNECTION created and co-ordinated by the super-librarian Dianne McKenzie of LibraryGrits fame (subscribe to her blog – it keeps me learning and thinking inbetween formal conference opportunities – she also writes some very interesting reflections as part of her COETAIL learning experience in “Wagging my Coetail”).

All the presentations were excellent, and Dianne had done a great job on creating themes around which the presentations were grouped. We also had the very talented Maggie Appleton doing some visual note taking (see below)

which was an exciting new development in PD for me – enhanced by Shirley Chan telling us how to involve our students (and ourselves) in visual note taking with some hand tips and tools of implementation. For example, a visual notetaking blog and a rather nice video for getting started

Other interesting bits and pieces were the talk on library advocacy – using the 6 principles of influence of Cialdini Reciprocity; Commitment (and Consistency); Social Proof; Liking; Authority and Scarcity from a course by Wendy Newman in Edx.

The ongoing genrefication of the non-fiction section.

Building a LOTE collection at an International School

Most international schools have a sizeable student population who speak a language other than English (LOTE), and offer language instruction in either mother tongue or second language at various levels. The question then is what role the school library plays in building a LOTE collection and how this can be financed and what other options exist.

Both the IBO (International Baccalaureate Organisation) and UNESCO encourage schools and learning communities to provide active support to promote learning and maintenance of mother tongue (Morley, 2006; UNESCO Bangkok, 2007). A school library’s aim should be to ensure that the LOTE collection supports the aims of the school for classroom instruction and external examination, pleasure reading and exposure to the literature of the various cultures of the campus community.

A review of the LOTE collection can be undertaken in the following steps: an overview of the existing collection; information gathering on the language profiles of the school community (students, parents, educators); understanding of the language provision at the school including mother tongue and second language acquisition; reviewing LOTE collections in the community; creating a LOTE collection development policy and other considerations.

Overview of the existing collection

Initially it is important to gain an overview of the school’s existing collection and how that is catalogued. If our school is anything to go by, there will be reading books, language text books (temporarily as they get loaned out at the start of the school year), and language teaching resources for teachers in the library. Those are the books we know of. However, depending on how tightly or loosely the library manages resources, individual language departments or teachers may have anything from vast to tiny collections in their classrooms purchased by departmental budgets (or often the purse of the teacher) which are neither catalogued by the library nor even known of outside of that department. This will differ from school to school depending on the amount of control the library has over resource budgets, the amount of sharing that goes on and the co-operation between the library and departments.

Even finding out the extent and location of resources can potentially be a political minefield, so proceed with caution and bear in mind what may seem to be an innocent question / request on your side may be misinterpreted on theirs …

Language profile of the school community

Try to understand the language profile of your school community. Are there any significant language groups within the student, parent or educator body? Think carefully where you get this information from – for example if the school is English medium, parents may put “English” as the mother tongue and the mother tongue as a second language or even omit other languages spoken at home completely in any admissions documents. Hopefully the school does some kind of census that is separate from the admissions process. Does the Parent Association have language or nationality representatives who can support the library, financially or otherwise?

Understanding school’s language provision

In addition you need to establish how many students follow which language streams in the various sections of the school, and gain an understanding of the various levels. Hopefully language teachers are cooperative and enthusiastic in explaining the needs of their students for books that encourage reading outside and around the curriculum and for pleasure, not just what is required in the classroom. They should also be able to help with the levelling of materials to ensure a culture of reading is sustained in all languages not just English and students are not frustrated with the complexity of materials available but the library has a range of materials at all difficultly levels.

Reviewing LOTE collections in the community

In the International / expatriate community, LOTE collections often exist outside of the school. Need for LOTE resources in a particular language is not necessarily a function of number of L1 (mother tongue) or L2 (second language) speakers. For example in Singapore, a few sizeable language communities (Korean, Japanese, and to a certain extent Dutch and French) rely on language and culture centres in Singapore spo

nsored in part by their National Governments, while the Singapore National Library holds Chinese, Malay and Tamil books. The role of the library would be one of collaboration and directing these populations to the relevant resource, (e.g. through the website and inter-library loans) rather than building up a potentially redundant collection. If the community has any International schools that focus primarily on one language (in Singapore this includes the German, French, Dutch, Korean and Japanese schools each with their own library), they could be approached for reciprocal borrowing or interlibrary loan privileges. Embassy and cultural attaches may be another source of funding or resources.

Creating a LOTE collection development policy

Depending on the size and status of the LOTE collection, it may not be necessary to create a separate LOTE collection development policy (CDP). LOTE collection issues can be dealt with within the overall CDP.

For example, the library strives to a goal of up to 20 books, excluding textbooks, per student. LOTE books can be expressed as a meaningful percentage per language of this aim.

Provision should be made for language teachers selecting books with input from parents or native speakers in the college community. Use can made of various recommendation lists including that of the IB Organisation (IBO) and collaborative lists of the International School Library Networks and language specialist schools.

Acquisition may be a tricky areas where books are either not available locally, are prohibitively expensive or are not shipped to the country. Provision often needs to be made for the acquisition by teachers, parents or students during home leave and reimbursed by the school. However, the budget and type of books needs to be vetted in advance so that there is little chance of miscommunication on either the cost or type of books thus acquired. A LOTE selection profile, such as that created by Caval Languages Direct (Caval. n.d.) can be adapted to fit the school’s needs.

As far as possible, it would be helpful if the library processes and catalogues all books which the school has paid for, irrespective of whether it came from the library budget or not. In this way, the real collection is transparent, searchable and available to the whole community (on request obviously for classroom / department materials) and to avoid duplication in acquisition or under-utilisation of materials.

Cataloguing LOTE materials can be a challenge, particularly if they are not in Latin script. It is important to still have cataloguing guidelines that are followed to ensure consistency and ease of search and retrieval. Our school makes use of parent volunteers and teachers who fill the data into a spreadsheet that is then imported into our OPAC system. Our convention is to have the title details in script, followed by transliteration, followed by translation in English. Search terms need to be agreed with by the LOTE collection users, such as language teachers and students.

As far as donations are concerned, the library still needs to have a clear policy on what books they accept and in what condition. Although donated books may be “free”, they are not without cost, including processing and cataloguing cost.

Apart from physical books, it is worthwhile looking at what resources are available online either as eBooks or as other digital resources. For example BookFlix and TumbleBooks offer materials in Spanish. Often individual language departments maintain their own lists and links to digital resources, which could be incorporated into a Library Guide and made available to the whole community.

Budget may be a contentious area and often language material discussions occur at administration or department level without the involvement of the library and an expectation may exist that the library will provide LOTE “leisure reading” materials within its overall resource budget perhaps without an explicit discussion on the matter or a breakdown between resources and budget of the various languages.

Other considerations

International schools are a dynamic environment, and a language group may be dominant for a period of time and then disappear completely due to the investment or disinvestment of multi-national companies in the area. IB schools face the need to provide for self-taught languages and any changes made by the IBO and the school from time to time. The IBO currently offers 55 languages, which theoretically could be chosen. The IBO introduced changes in its language curriculum in 2011, substantially increasing the number of works that need to be studied in the original language rather than in translation. This places an additional burden on the library to have sufficient texts in the correct language available on time.

The socio-economic demographic of students with LOTE needs should also be considered. If most of the student body comes from a privileged background where LOTE books are purchased during home leave, the school could institute donation drives where “outgrown” books are donated to the school. It would be more equitable to use resources for scholarship students in order to maintain their L1 even if these languages do not form a large part of the communities’ LOTE.

The quality of materials in Southeast Asian languages is generally extremely poor. The cost of acquiring, processing and cataloguing the materials far exceeds the purchase price and books deteriorate rapidly. There is considerable scope for moving to digital materials, however the availability, format, access, licensing issues and compatibility will have to be investigated.

Schools, in conjunction with parents, needs to consider language provision for students who plan on returning to a LOTE university after graduation.

Centres of Excellence

A literature review suggests that the centre for excellence and expertise in building LOTE collections is Victoria Australia, (Library and Archives Canada, 2009), in fact the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Multicultural Communities Guidelines for Library services is based on their guidelines (IFLA, 1996). These guidelines suggest the four steps of; needs identification and continual assessment, service planning for the range of resource and service need, plan implementation and service evaluation.

Some LOTE Digital resources

http://librivox.org/about-listening-to-librivox/

http://www.radiobooks.eu/index.php?lang=EN

http://www.booksshouldbefree.com/language/Dutch

http://www.childrenslibrary.org/icdl/SimpleSearchCategory

Library services

http://www.lote-librariesdirect.com.au/contact/

http://www.caval.edu.au/solutions/language-resources

http://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/lotelibrary/index.html

http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/services/multicultural/multicultural_services_public_libraries.html

http://www.reforma.org/content.asp?pl=9&sl=59&contentid=59

http://chopac.org/cgi-bin/tools/azorder.pl

http://civicalld.com/our-services/collection-services

References

American Library Association. (2007). How to Serve the World @ your library. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.ala.org/offices/olos/toolkits/servetheworld/servetheworldhome

International Baccalaureate Organisation. (2011). Guide for governments and universities on the changes in the Diploma Programme groups 1 and 2. IBO. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/recognition/dpchanges/documents/Guide_e.pdf

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (1996). Multicultural Communities Guideline for Library Services. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://archive.ifla.org/VII/s32/pub/guide-e.htm

Kennedy, J., & Charles Sturt University. Centre for Information Studies. (2006). Collection management : a concise introduction. Wagga Wagga, N.S.W.: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

Library and Archives Canada. (2009). Multicultural Resources and Services – Toolkit – Developing Multicultural Collections. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/multicultural/005007-302-e.html

Morley, K. (2006). Mother Tongue Maintenance – Schools Assisted Self-Taught A1 Languages. Presented at the Global Convention on Language Issues and Bilingual Education, Singapore. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/news/documents/morley2.pdf

Reference & User Services Association. (1997). Guidelines for the Development and Promotion of Multilingual Collections and Services. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines/guidemultilingual

UNESCO Bangkok. (2008). Improving the Quality of Mother Tongue-based Literacy and Learning Case Studies from Asia, Africa and South America. UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education Asia-Pacific Programme of Education for All (APPEAL). Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001777/177738e.pdf

Creative Commons License

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.