Most international schools have a sizeable student population who speak a language other than English (LOTE), and offer language instruction in either mother tongue or second language at various levels. The question then is what role the school library plays in building a LOTE collection and how this can be financed and what other options exist.

Both the IBO (International Baccalaureate Organisation) and UNESCO encourage schools and learning communities to provide active support to promote learning and maintenance of mother tongue (Morley, 2006; UNESCO Bangkok, 2007). A school library’s aim should be to ensure that the LOTE collection supports the aims of the school for classroom instruction and external examination, pleasure reading and exposure to the literature of the various cultures of the campus community.

A review of the LOTE collection can be undertaken in the following steps: an overview of the existing collection; information gathering on the language profiles of the school community (students, parents, educators); understanding of the language provision at the school including mother tongue and second language acquisition; reviewing LOTE collections in the community; creating a LOTE collection development policy and other considerations.

Overview of the existing collection

Initially it is important to gain an overview of the school’s existing collection and how that is catalogued. If our school is anything to go by, there will be reading books, language text books (temporarily as they get loaned out at the start of the school year), and language teaching resources for teachers in the library. Those are the books we know of. However, depending on how tightly or loosely the library manages resources, individual language departments or teachers may have anything from vast to tiny collections in their classrooms purchased by departmental budgets (or often the purse of the teacher) which are neither catalogued by the library nor even known of outside of that department. This will differ from school to school depending on the amount of control the library has over resource budgets, the amount of sharing that goes on and the co-operation between the library and departments.

Even finding out the extent and location of resources can potentially be a political minefield, so proceed with caution and bear in mind what may seem to be an innocent question / request on your side may be misinterpreted on theirs …

Language profile of the school community

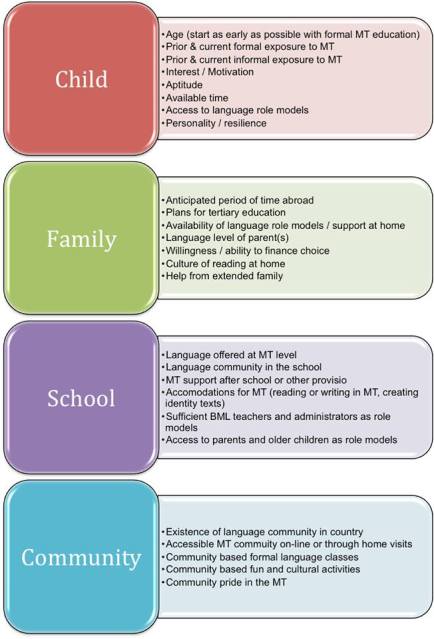

Try to understand the language profile of your school community. Are there any significant language groups within the student, parent or educator body? Think carefully where you get this information from – for example if the school is English medium, parents may put “English” as the mother tongue and the mother tongue as a second language or even omit other languages spoken at home completely in any admissions documents. Hopefully the school does some kind of census that is separate from the admissions process. Does the Parent Association have language or nationality representatives who can support the library, financially or otherwise?

Understanding school’s language provision

In addition you need to establish how many students follow which language streams in the various sections of the school, and gain an understanding of the various levels. Hopefully language teachers are cooperative and enthusiastic in explaining the needs of their students for books that encourage reading outside and around the curriculum and for pleasure, not just what is required in the classroom. They should also be able to help with the levelling of materials to ensure a culture of reading is sustained in all languages not just English and students are not frustrated with the complexity of materials available but the library has a range of materials at all difficultly levels.

Reviewing LOTE collections in the community

In the International / expatriate community, LOTE collections often exist outside of the school. Need for LOTE resources in a particular language is not necessarily a function of number of L1 (mother tongue) or L2 (second language) speakers. For example in Singapore, a few sizeable language communities (Korean, Japanese, and to a certain extent Dutch and French) rely on language and culture centres in Singapore spo

nsored in part by their National Governments, while the Singapore National Library holds Chinese, Malay and Tamil books. The role of the library would be one of collaboration and directing these populations to the relevant resource, (e.g. through the website and inter-library loans) rather than building up a potentially redundant collection. If the community has any International schools that focus primarily on one language (in Singapore this includes the German, French, Dutch, Korean and Japanese schools each with their own library), they could be approached for reciprocal borrowing or interlibrary loan privileges. Embassy and cultural attaches may be another source of funding or resources.

Creating a LOTE collection development policy

Depending on the size and status of the LOTE collection, it may not be necessary to create a separate LOTE collection development policy (CDP). LOTE collection issues can be dealt with within the overall CDP.

For example, the library strives to a goal of up to 20 books, excluding textbooks, per student. LOTE books can be expressed as a meaningful percentage per language of this aim.

Provision should be made for language teachers selecting books with input from parents or native speakers in the college community. Use can made of various recommendation lists including that of the IB Organisation (IBO) and collaborative lists of the International School Library Networks and language specialist schools.

Acquisition may be a tricky areas where books are either not available locally, are prohibitively expensive or are not shipped to the country. Provision often needs to be made for the acquisition by teachers, parents or students during home leave and reimbursed by the school. However, the budget and type of books needs to be vetted in advance so that there is little chance of miscommunication on either the cost or type of books thus acquired. A LOTE selection profile, such as that created by Caval Languages Direct (Caval. n.d.) can be adapted to fit the school’s needs.

As far as possible, it would be helpful if the library processes and catalogues all books which the school has paid for, irrespective of whether it came from the library budget or not. In this way, the real collection is transparent, searchable and available to the whole community (on request obviously for classroom / department materials) and to avoid duplication in acquisition or under-utilisation of materials.

Cataloguing LOTE materials can be a challenge, particularly if they are not in Latin script. It is important to still have cataloguing guidelines that are followed to ensure consistency and ease of search and retrieval. Our school makes use of parent volunteers and teachers who fill the data into a spreadsheet that is then imported into our OPAC system. Our convention is to have the title details in script, followed by transliteration, followed by translation in English. Search terms need to be agreed with by the LOTE collection users, such as language teachers and students.

As far as donations are concerned, the library still needs to have a clear policy on what books they accept and in what condition. Although donated books may be “free”, they are not without cost, including processing and cataloguing cost.

Apart from physical books, it is worthwhile looking at what resources are available online either as eBooks or as other digital resources. For example BookFlix and TumbleBooks offer materials in Spanish. Often individual language departments maintain their own lists and links to digital resources, which could be incorporated into a Library Guide and made available to the whole community.

Budget may be a contentious area and often language material discussions occur at administration or department level without the involvement of the library and an expectation may exist that the library will provide LOTE “leisure reading” materials within its overall resource budget perhaps without an explicit discussion on the matter or a breakdown between resources and budget of the various languages.

Other considerations

International schools are a dynamic environment, and a language group may be dominant for a period of time and then disappear completely due to the investment or disinvestment of multi-national companies in the area. IB schools face the need to provide for self-taught languages and any changes made by the IBO and the school from time to time. The IBO currently offers 55 languages, which theoretically could be chosen. The IBO introduced changes in its language curriculum in 2011, substantially increasing the number of works that need to be studied in the original language rather than in translation. This places an additional burden on the library to have sufficient texts in the correct language available on time.

The socio-economic demographic of students with LOTE needs should also be considered. If most of the student body comes from a privileged background where LOTE books are purchased during home leave, the school could institute donation drives where “outgrown” books are donated to the school. It would be more equitable to use resources for scholarship students in order to maintain their L1 even if these languages do not form a large part of the communities’ LOTE.

The quality of materials in Southeast Asian languages is generally extremely poor. The cost of acquiring, processing and cataloguing the materials far exceeds the purchase price and books deteriorate rapidly. There is considerable scope for moving to digital materials, however the availability, format, access, licensing issues and compatibility will have to be investigated.

Schools, in conjunction with parents, needs to consider language provision for students who plan on returning to a LOTE university after graduation.

Centres of Excellence

A literature review suggests that the centre for excellence and expertise in building LOTE collections is Victoria Australia, (Library and Archives Canada, 2009), in fact the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Multicultural Communities Guidelines for Library services is based on their guidelines (IFLA, 1996). These guidelines suggest the four steps of; needs identification and continual assessment, service planning for the range of resource and service need, plan implementation and service evaluation.

Some LOTE Digital resources

http://librivox.org/about-listening-to-librivox/

http://www.radiobooks.eu/index.php?lang=EN

http://www.booksshouldbefree.com/language/Dutch

http://albalearning.com

http://www.wdl.org/en/

http://www.childrenslibrary.org/icdl/SimpleSearchCategory

http://www.dawcl.com

http://unterm.un.org

Library services

http://www.lote-librariesdirect.com.au/contact/

http://www.caval.edu.au/solutions/language-resources

http://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/lotelibrary/index.html

http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/services/multicultural/multicultural_services_public_libraries.html

http://www.reforma.org/content.asp?pl=9&sl=59&contentid=59

http://www.cacaoproject.eu

http://chopac.org/cgi-bin/tools/azorder.pl

http://civicalld.com/our-services/collection-services

References

American Library Association. (2007). How to Serve the World @ your library. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.ala.org/offices/olos/toolkits/servetheworld/servetheworldhome

International Baccalaureate Organisation. (2011). Guide for governments and universities on the changes in the Diploma Programme groups 1 and 2. IBO. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/recognition/dpchanges/documents/Guide_e.pdf

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. (1996). Multicultural Communities Guideline for Library Services. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://archive.ifla.org/VII/s32/pub/guide-e.htm

Kennedy, J., & Charles Sturt University. Centre for Information Studies. (2006). Collection management : a concise introduction. Wagga Wagga, N.S.W.: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.

Library and Archives Canada. (2009). Multicultural Resources and Services – Toolkit – Developing Multicultural Collections. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/multicultural/005007-302-e.html

Morley, K. (2006). Mother Tongue Maintenance – Schools Assisted Self-Taught A1 Languages. Presented at the Global Convention on Language Issues and Bilingual Education, Singapore. Retrieved from http://www.ibo.org/news/documents/morley2.pdf

Reference & User Services Association. (1997). Guidelines for the Development and Promotion of Multilingual Collections and Services. Retrieved January 4, 2013, from http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines/guidemultilingual

UNESCO Bangkok. (2008). Improving the Quality of Mother Tongue-based Literacy and Learning Case Studies from Asia, Africa and South America. UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education Asia-Pacific Programme of Education for All (APPEAL). Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001777/177738e.pdf

Creative Commons License

This work by Nadine Bailey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.