During the vacation I’ve been catching up with some podcasts, including listening to a few new ones that were recommended to me by friends. While there are some great educational podcasts out there, sometimes while one is looking outside of the field that you are struck by things that are relevant.

So it was with this podcast from “You are not so Smart” based on research on how to deal with climate deniers with Per Espen Stocknes.

Because sometimes (most the time) when looking at reluctant readers I’m pretty sure I’m missing the boat on how to communicate effectively and meaningfully with them. Like the time I asked a group why they thought I kept trying to get them to read more and they basically said “because it’s your job Ms!”

So the thing is, there are 5 different ways that you can mess up your communication, which result in the “backfire effect” whereby people negate your message and turn all defensive on you. So you’d be better off saying nothing, than saying something that gets folks’ psychological back’s up. While the talk related this to climate change I’ll re-interpret them along the lines of getting kids and their families (and even gasp, teachers) to read more, read together, read-aloud.

- Doom and Gloom

- Distance

- Dissonance

- Denial

- iDentity

In the doom and gloom scenario you’re telling kids that if they don’t read they’re going to fail, drop out, go to prison, not get a good job, not get into college etc. if they don’t read. Psychologically this leads to a guilt and fear mind frame in the audience, increased passivity and avoidance. When what we really want is for parents and students to jump into action with a plan of daily reading! Another problem with those messages – it’s all too abstract and too distant. It’s the issue that that the problematic future is well, in the future, and right now they’d rather be playing an online game, or kicking a soccer ball. The locus of control is also presumed to be outside their scope of influence, there is reduced urgency and personal agency leading to a feeling of helplessness.

Cognitive dissonance is a very tricky thing when dealing with parents. Every parent, no matter what they may be struggling with privately or publicly with their children have to be believed to be doing the best they can with the knowledge and tools at their disposal. Ditto teachers (I include teachers as there are many teachers who do not read, and do not find reading pleasurable, and struggle with “walking the talk”). When people tell you that you should be reading to your child or reading more, or reading differently that kind of flies in the face of your image of yourself as a good and successful parent and person. And so what one often hears is “I/my husband / his grandpa/ never was much of a reader, and they turned out OK” or even “we have plenty of books at home” or “he/she borrows books every week“. All of which may be perfectly true, even if those books may never be opened and read … and it’s the “right” answer to shut up a concerned teacher / librarian.

Denial is another mechanism frequently employed – one comes out with some latest research or study that reading is the answer to life, the universe and everything, and all sorts of things get thrown back at you – like “I read that if you read online it’s not effective” or “all they want to read is graphic novels” or some kind of moral licensing – “but he/she is very involved with the school play / the band / Kumon worksheets and doesn’t have the time for reading” and “he/she is doing just fine in class” or even worse “but X is struggling much more“.

The final point has to do with identity. Everyone, from young students up need to protect their self-esteem and keep their identity intact. For some of my students it’s very important to be cool. And being cool doesn’t involve struggling or appearing to struggle at anything. For many families caught up in the fairyland of expatriate existence, a veneer of “everything is fine” is also very important. Problems with reading – fluency, comprehension, language, and admitting to those problems does not gel with that identity. At this point a lot of blame gets thrown around. The teacher who didn’t teach properly. The librarian who put them off borrowing after they lost a book. The teacher who won’t let them borrow batman books or insists on “just right” books. It’s a tough one and part of what we attempted to do with “Blokes with Books” is to make reading cool and social.

Right, so what to do about this. There were 5 solutions offered by Stocknes and I’ll relate these to what I’m trying to do, and plan to do in the new school year.

- Social

- Signals

- Simple

- Supportive

- Storytelling

Keeping things social is something I absolutely subscribe to. As I’ve said so often before, contrary to belief, reading is not a solitary activity. It is social. The kind of things that my students enjoy are book clubs, sitting and reading the same book at the same time and turning the pages at the same time. Reading in a group of three of four and raucously pointing at things and exclaiming.

Feedback and signals need to be those that people can relate to and are relevant.The antidote to distant gloom and doom is making things near and personal, since good behaviour can be contagious – particularly if it’s acknowledged and there is some positive comparison going on. Now this works brilliantly with electricity consumption in the examples given, but I’m a little wary of competitive reading. Cue in all the research done by Krashen et.al and the dangers of extrinsic versus intrinsic rewards and the virtues of free voluntary reading. I’d be the last to deny that (some) kids appear to be motivated by reading points, scores, levels etc. But I’m still not prepared to make that the focus of my efforts. I’ve been thinking long and hard about what kind of comparisons are relevant and meaningful. One that I’ve used on my students has been to work out the median number of books students in their class and grade read each month and ask them to compare themselves. The best thing we’ve done for our reluctant (male) readers has been the “blokes with books” club, which has helped both with identity and social belonging.

Schools and homes are incredibly busy environments. It’s imperative to keep things simple and easy, with low barriers. Some things I’ve already put in place, like allowing students to borrow books on four occasions daily (before and after school at recess and at lunch) on any day of the week, in addition to their normal weekly library lesson with their class. There kind of are limits on the number of books they can borrow based on their age, but they all know that’s negotiable. Likewise parents can now join and supposedly borrow three books at a time, but we have some parents who borrow more and one who gets around 10-20 every Friday, as she’s a working parent and doesn’t get to the library every day. I don’t mind, as long as they keep returning. Classroom libraries are also a great way of ensuring books are in the hands of students. That still needs more work. All our classes have class-libraries, but they’re not functioning optimally. This is a loaded area. The library is “my” domain (but not really) and the class “theirs”, so I can implement best practice with abandon in the former and have to tread carefully in the latter. What would I like to see / do differently? More movement more regularly in the class libraries – now books are checked out for the year. Self-checkout / check-in in the classrooms – my fault in prior years and I really need to get that going this year. More weeding of old, tattered and yucky books – it’s starting to happen. Nicer display – need to think about that as it’s definitely crossing the line. Maybe a workshop on class libraries?

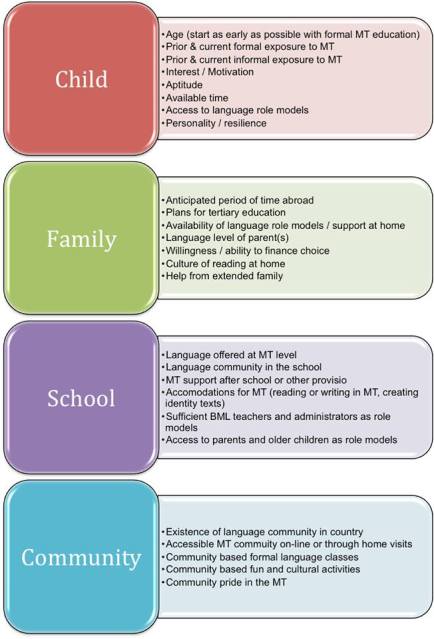

Providing a supportive framework – takes time. Time for you to get to know the students, the teachers the parents. Sticking to the message of the importance of reading without the judgement. Being there and listening when one of the parts of the reading ecosystem need to unburden or get a book list or suggestions without jumping to conclusions or formulaic solutions. I’m incredibly fortunate to have a supportive administration and principal and (so far) an adequate budget, and library assistants who are buying into creating an environment conducive to encouraging reading.

Finally incorporating the storytelling format in communication. Stories need to be personal and individual and incorporate an element of dream actualisation. I’ve been doing a bit of this around the PYP and Singapore environment (most recently at the AFCC), the stories of the gains my formerly reluctant readers have made compared to their peers really is motivating. Success stories are wonderful. But struggle stories are also relevant, and the fact that I have a reluctant reader at home keeps things real and personal. I have no pedestal to preach from as I’ve been exposed to every excuse, every battle, and tried every possible solution myself and I’m still only partially successful in my efforts.

As the new school year starts I hope all your reading dreams for your students come true!